10 Timeless Gems from Middle-Earth

Here are some of our favorite Tolkien names. What are yours?

J.R.R. Tolkien’s names have it all. They’re beautiful and evocative. They’re magical, thoughtful and sturdy. He both invented languages and drew from existing ones. He showed through his love of the origin, sound and look of words and names, that they could reconnect us with the past, illuminate the present, and bring a sense of destiny about the future.

That his names are a synthesis of history, mystery and creativity is what makes them so enduring and fascinating. To us, each one is a magical spell. So here are ten of our favorites from Tolkien’s mythology with some backstory on each:

Curufinwë — Say what!? Say it with us, “Koo-Roo-Fin-Way”! Now exhale and let it rip round your cranium like muttering monks and sleigh bells. Here’s just how deep it goes: Fëanor, the most powerful Elf in Tolkien’s mythology, who created the Silmarils and instigated the exodus of the Elves from the land of the gods and back to Middle-earth, setting in motion the major events that shape and drive the narrative of The Silmarillion, was known in his youth as Curufinwë. His father was Finwë, so Curufinwë suggests “skilled Finwë” in Quenya, the ancient language, or “Latin,” of the Elves. He was originally born with the name Finwion, but when he showed great skill at crafting things, Curufinwë became his new name, before it then became Fëanor, which means “spirit of fire.” The suffix -wë, generally associated with male names in Quenya, is applied to many other noteworthy characters, such as Elwë and Olwë (brothers who led the Wood-Elves and Sea-Elves), Manwë (the king of the gods), and Voronwë (a mariner who is washed back from the sea after seeking help from the gods, and then meets Tuor and takes him to a city of the Elves, where Tuor becomes the father of Eärendil, the savior, as it were, of the First Age). It’s got a rhythm. But… They’re not just mnemonic devices to help us wade through a mythology as dense as Tolkien’s, but they’re also little musical melodies that take you on a trip. So we love Curufinwë not only because of its intricate history, but for the way it rolls off the tongue. It’s practically supernatural. “Curu” has an almost Asiatic, Japanese sound to it, and yet it fits evocatively next to the more European sounding Finwë, which relates closely to Ingwë and the Swedish Yngve. It also dazzles the eyes. Whip it all together, and you get, “Can you feel me?”

Mormegil — Now let’s get a little more serious. There is a misperception that Tolkien’s stories don’t have a lot of grey, that they are too “black and white.” It is true he accentuated two ends of the spectrum, of light and shadow, of good and evil. But those polarities stretch our spirits, as his worlds are filled to the gills with grey, when you step outside of internal psychology and think more in terms of embodied dreams and mythic archetypes. Gollum is his greatest avatar of the grey, of the struggle and the bending between these primal valences of the human psyche. But Gollum is far from Tolkien’s only paragon of spiritual conflict. Before Gollum was Túrin, son of Húrin, one of the greatest human warriors in The Silmarillion. He is a dark and tragic hero modeled after the Kalevala’s hapless Kullervo. Tolkien brings a number of innovations to the Finnish archetype, not least of which is his meta-narrative, shaped like the twisted movements and tangled mind of Túrin’s nemesis, the dragon Glaurung, known also as the Great Worm — worming into the mind and soul. Many Tolkien fans are not as familiar with The Children of Húrin, which tells the tale of Túrin Turambar. It involves incest, murder and suicide. In many ways, along with much of The Silmarillion, it is the original Game of Thrones, filled with brutality and death. One key to the story is Túrin’s magical talking sword, made of black meteoric iron, called Anglachel. For this reason, the Elves call him Mormegil, which means “black sword.” We love the name because of its alliterative syllables “Mor-” and “-me-,” followed by the rolling “-gil” — phantasmagoric, mellifluous and melancholic all at once.

Gondolin — Before Minas Tirith, there was the Elven city of Gondolin. The Fall of Gondolin is the first story Tolkien wrote in his Book of Lost Tales, his earliest attempt at a grand mythology that would plant the seeds for The Silmarillion, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Founded by Turgon, it was a hidden city built inside encircling mountains. In the great wars against Morgoth (the predecessor to Sauron), it is the last great bastion of the Elves. It is a multi-tiered white city resplendent in the sun, like Minas Tirith. It had seven names, all of them compelling, like Loth and Gwarestrin, but Gondolin is the best. We love Gondolin because it is muscular yet melodic — a bit like a gondola and its gondolier in Venice, yet wintry and alpine — like frozen waves in meringue and snow.

Ecthelion — One of the great heroes of The Fall of Gondolin is Ecthelion, Lord of the Fountains. He is one of the captains of Turgon’s guard and fights valiantly when Gondolin is finally found by Morgoth and attacked. Ecthelion kills three Balrogs and the Lord of the Balrogs, Gothmog, sacrificing himself so Tuor and his family can escape, thus saving Eärendil, Tuor’s son, and securing the last hope for deliverance from Morgoth and his evil. Ecthelion is not a major character in Tolkien’s mythos, but like Glorfindel, he is a mighty light in darkness. We love the name Ecthelion because of how unusual it is. Like “eclipse,” the “Ec-” prefix propels what follows, and in this case, it’s the fluid musicality of “-thelion” that gives it an emphatic noble lilt.

Rivendell — There is perhaps one name more than any in Tolkien’s stories that signifies rest and shelter, a Shangri-La where all cares can be washed or dreamed away in peace and contemplation. Rivendell was first imagined as the “Last Homely House west of the Mountains” in The Hobbit. It’s the great House of Elrond, where weary travelers can replenish and find wisdom. It has a wonderful Elven name too, Imladris. But it’s the combination of the “n” at the end of “Riven-” and the “d” of “-dell” that makes its spry English construction so good, as well as how “riven” and “dell” so perfectly describe what it is. We also love it not just because of what it represents in Tolkien’s stories, but how it has come to represent in the common vernacular an ideal place of restoration, the sharing of stories and warmth at the hearth. Who wouldn’t want to go there?

Bilbo Baggins — It’s not elevated or refined, one might say. But Bilbo Baggins is one of the greatest names in all of literature and mythological world-building. Its alliterative “Bil-,” “-bo,” and “Baggins” hit such a pleasing melody, that it’s no wonder the actor Sir Ian McKellen so relished saying it in The Fellowship of the Ring, as he admonished the little hobbit. Of course, once Baggins was established as the most storied surname in all of adventure fiction, giving it to Frodo did just as many wonders for Bilbo’s more serious, soulful and melancholy cousin. There is a fascinating etymological background to “Baggins,” that Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey breaks down masterfully in his essential book, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. I’m not going to spoil it here. It’s a great read.

Gwaihir — One of the best characters in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and the embodiment of deus ex machina (i.e. “the eagles are coming!”), is Gwaihir, lord of the Eagles of the North. Gwaihir (pronounced “Gwa-I-Heer”), saves Gandalf, Thorin and Company, and Frodo and Sam, at key points in Tolkien’s mythology. He’s basically an angel of nature. Fittingly, his name means “Wind Lord.” One of the main criticisms of The Lord of the Rings’ plot is “Why didn’t Gwaihir just drop the Ring of Power into the fires of Mordor and save everyone all the bother?” The common answer these days is that the Eagles were not a Middle-earth taxi or postal service. The reason most fail to see, however, is very obvious. The Nazgûl had winged Fell beasts, which they rode after they and their horses were wiped out at the Ford of Bruinen. So Mordor had an air force. Also, there is a Dark Lord called Sauron who could probably incinerate them too in some fashion. The Eagles don’t rescue Sam and Frodo until after the Ring of Power is destroyed, by which the skies of Mordor then become friendly skies. But the reason we also love the name Gwaihir, besides all of his badass exploits as described above, is that the name itself somehow expressed a sense of not only flight but his nobility. “Gwai-” has a great sense of swoop and lift while “-hir” sounds distinctly regal, like the words “heed” and “hail” and “high.” “Gw-” is uncommon in names, except for Gwen, Gwyneth or Gwendolin. Those are Welsh names and clearly they influenced Tolkien. The latter perhaps even influenced Gondolin, which was perhaps an inspired synthesis of “Gwendolin” and “gondola”? You also have names and words like Guam and Guava. But it’s constructing the visual look of “Gwa-” with the “high” in “Gwai-,” and the elevated “-hir,” that makes seeing and hearing “Gwaihir” so delightful.

Utumno — Utumno is an odd one and that’s why we love it. It contains within it those Finnish idiosyncrasies that make other Quenya names like Cuiviénen, Hísilómë, Curufinwë and Singollo so magnificent. One can see a line from Kullervo to Utumno, but the latter is still pure Tolkienian. Utumno is Morgoth’s initial hideout early in The Silmarillion, an icy underground fortress in northern Middle-earth, where he likely first gathered the Balrogs to him, deformed Elves into Orcs, and bred the Great Spiders. In Sindarin, Tolkien’s Welsh-inspired Elvish language, different from his Finnish-inspired Quenya, it is translated as Udûn. This is where part of the famous command made by Gandalf to the Balrog in Moria comes from. “I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the Flame of Anor,” he says. “You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the Shadow.” Udûn is great too. It is succinct and primal. But we love Utumno for the musical quality of the “no” at the end, made all the more singular with the “m” before it, with “Utum” (pronounced “Oo-Tum”) giving it an almost kick drum sound, while also clearly showing its connection to “Udûn.” It’s mind-boggling how Tolkien brought the two names into harmony yet made them so alien to each other. It’s brilliant in its elegant double-mindedness.

Tulkas — Another great short name in The Silmarillion is Tulkas. It has an intense pulse to its “Tulk-” and its “-as,” shifting and depending on where you emphasize the “k” in your enunciation, like a sulk or a kiss. He is the god (or Vala), who delights in battle and wrestling, laughing as he sends fear into the hearts of his dark foes. The Valar have many great names, and they are the first highly Quenyan forms that we learn when we read the count of the Valar, in the Valaquenta, early in Tolkien’s “Bible.” There is Manwë and Mandos, Varda and Vairë, Yavanna and Ulmo, Irmo and Estë, Oromë and Vána, and Aulë, Nienna and Nessa. But Tulkas is the one that seems to break away from the forest of soft ethereal Valar names. It’s the “k” that then gives it such strength, and the “Tul-” and the “-kas” working together that gives it such a singular wild-man force, like a two-note backbeat.

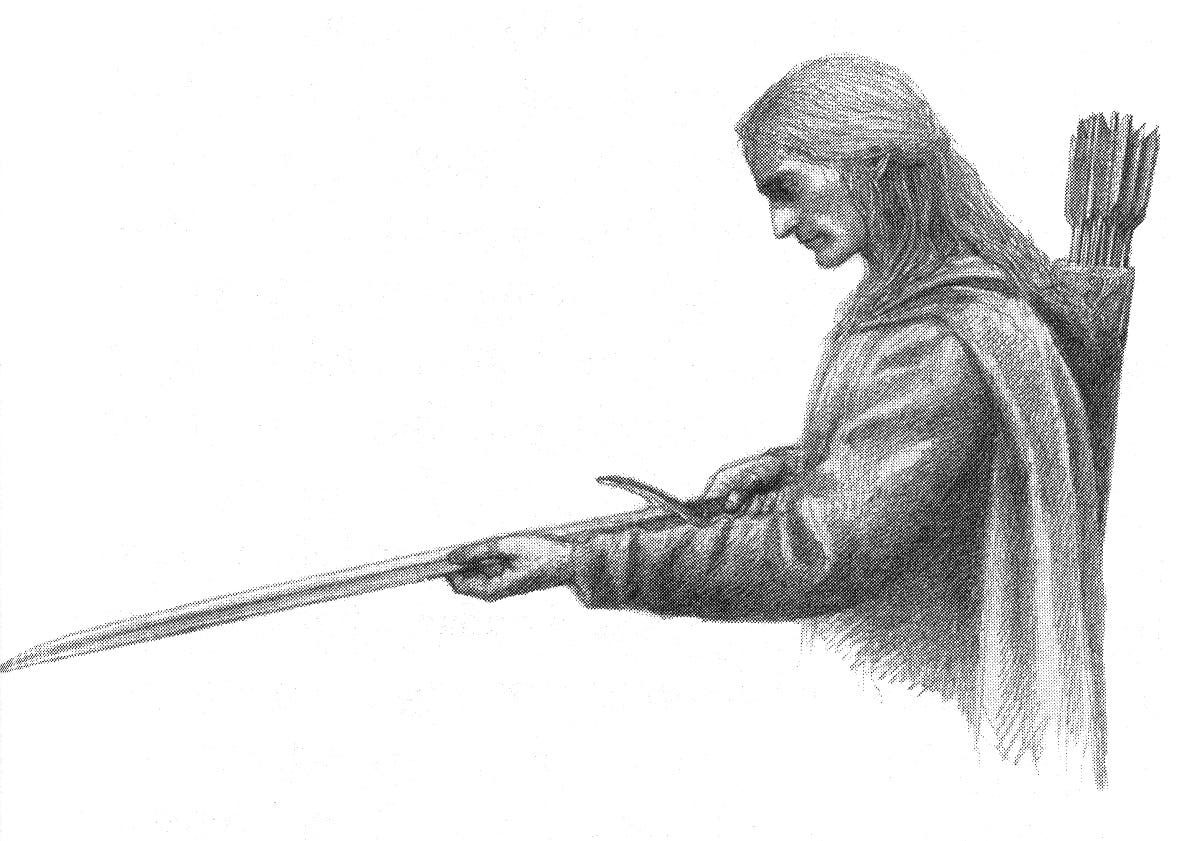

Legolas — There is no denying that the Fellowship of the Ring is graced with many great names in its fabled company of nine. “Aragorn” has the sound of both a sensitive yet fierce people. “Gandalf” took an existing name in Old Norse and transformed it into the ur-wizard, more so even than Merlin. “Boromir” has the sound of a Boris meets an Emir. It sounds every bit the name of a strong, hardy brooding man. “Gimli” is from Icelandic and Viking myth, originally the name of where the worthy survivors of Ragnarök are foretold to live. Applying it to a red-bearded dwarven prince, Tolkien turned it into the very definition of gentleness. The hobbits all have great names too: Peregrin, Meriadoc, Samwise and Frodo. Tolkien enriches them with interesting surnames: Took, Brandybuck, Gamgee and Baggins. They are the perfect counterpoint to the five other heroic names. Legolas of course is the one we’re selecting here as our favorite, though it could easily be any of them on another day, especially Gandalf, Frodo and Samwise. But we love “Legolas” for how it offsets so many of the other Elven names in Middle-earth. It has a Grecian quality reminiscent of the Homeric Age. Think Achilles, Menelaus or Odysseus. And yet the “Leg-” or “Leg-O-” gives it both a Germanic and slightly Italian air. The Harvard Lampoon’s Bored of the Rings famously made some humorous hay of its unusual letter patterns, changing it to Legolam, as in “leg of lamb.” But despite that cute play on sounds, Legolas remains an at once simple yet eloquent name. It’s hard to understand why exactly. Is it the “go-las” right after the soft and open “Le-”? Is it the look of it, the upward “L” and the downward “g” followed by the alliterative “las”? It’s all of those things at once perhaps. Whatever the case, it’s one of a kind — a Tolkien classic. It’s like an arrow shooting high in the sky. It’s simply magic.

Please tell us about your favorite Tolkien names in the Comments below, or share them on social media. Shout them from the tops of mountains. Whisper them with your next cocktail. And if you want to know more about why Tolkien’s names are so timeless and why they stand out from other fiction universes, go here to read our article, In the Beginning Was the Name.