Low Owl -:- Butterfly World

Book One, Chapter One

From the top of a valley in a wood chamber, she dreamed of a watchtower at the edge of the world from where she could perceive an endless sea, its restless waves striding like giants from across the horizon. She heard the howls of a hound echo through the stars, answered by the howls of another, and another. Then peering into darkness, she saw a firebird ignite a brilliant light-storm, flashing and burning from one end to the other, striking a daring ship. Then nothing.

It all went dark. In her hand was a lamp. Raising it to guide her, she walked down a spiral of stairs. And wandering out of sleep, she opened her eyes.

Up on the chamber wall, awake, she watched dappled light move in gentle tides around her, blots of thought crossing into the void. A shadow clock turned with many hands, each representing a planet, a moon, a sun, making an infinitesimal hum. Not a circle within circles, but many circles askance, with faces and gears invisible to sight hidden in a trick of darkness and splintered light.

Made in the mold of ancient time chambers, its shadows turned in countless interlocking rhythms. Her thoughts turned too, folding in on themselves like clouds backlit by suns and moons, drawing her gaze from day to night, and night to day. Time was refracted in glass prisms, the morning sunlight from the window striking dead centers and escaping in rainbows; the room’s secret faces and gears angling rays as they spun with the Earth, sending different colors this way and that in dazzling gleams, kindling her mind into sunrise.

But what fit in the chamber, was just reflections. The night before, she had seen the brightest meteor skitter and scatter and blaze across the sky. Its sharp bursts and streaks of fire reminded her of a stone skipping on water. Each skip was a ring — an eddy in an infinite stream. Its path was so bright, she thought she heard it thunder and roar. But it was just her mind reeling from the shock of waves crashing over buried wells of distant dreams and childhood memories.

She had never seen anything like it, save maybe as a baby in the first starkness of daylight. Yet that, she could not remember. She could only imagine it.

Heaven and earth were one and the same, she was told. The Great Ice was receding and the glaciers were in retreat, with rivers and lakes left in their wake. She wondered about the origins of the voyagers from afar on winding roads that followed the rivers among the stars, the planets that sneaked by, the moon that played the fool, and the sun that turned darkness to its rule.

Where did they come from and where did they all lead? Was there some long lost door? Was there a window up in the sky from which gods and demons stared out? Were they messengers that she sent back to herself from a future so far that it was the beginning once more? That last thought was a strange one, but something told her time warped high up in the firmament and deep down in the spirit.

Cutting across those horizons in her mind was a whispering stream that ran through the northwest corner of the meadow that her woodland lodge was built upon. Its crystal clear and cold meltwaters babbled over rocks and tumbled trees. Its dulcet notes were a great relief to her, constantly replenishing and slaking her soul with its gentle yet tireless music. Listening to its endless sound, she tried to imagine where all its burbling was coming from that made up its amalgam, but all that she could picture were little pebbles and eddies and splashes that reminded her of the stars. She had wondered, did all the waves and currents of the world’s waters, since the beginning of time, outnumber the flickering fires in the sky?

It made her realize that time flowed like a stream in one direction, but that it also went in circles, and as she had done so many times when she stood in the stream, it slowed or even stopped, at least in her mind. She had hunted many times along its course, surprising elk and wolverines, hiding her careful steps in its murmurs. At night or under moonlight, she could even hunt herons and mallards. In the starlit darkness, the mirror-rills of the riverland flowed into the vast un-light.

Musing on, she knew that every hunter followed twilight tributaries to the cities of gods, shining on high, destinations that decided fates of all-world tribes. From her lookout lodge, she had watched for tidings from estranged nations, the march of seasons, studied their signals from night skies, and wondered about the fires of empire and war. That was the riddle hidden in black holes and the stars — fateful sparks in the great spans of time stretching beyond the mind — and why she was learning how to read and chart the heavens. She was seeking clairvoyance.

Yet the world no longer waited. And she knew its hunger had no limits. She was hunting for others who could not hunt. That’s how they survived. By early spring, she was out setting traps, tracking deer, boars and rabbits, and foraging what she could in the cold Uplands. It was her uncle who trained her, a great bowman who explored and watched the shadowlands east of the great forest city of Gamak, the dunes of Drathirz to the north and over the Straits of Simbesh onto Araíyek and then south to enduring Avaray and vibrant Dassint.

His name was Kúlluvía. He was on a long journey over land and sea tracking the comet Razakusa as it moved east toward the planet Kyristala, the Wandering One. Following its tail, he was looking for signs of how the ice shifts had buried empire after empire in the drifts of time. The lantern in the hermitage had grown brighter and brighter, for Razakusa had been caught in its chamber. Sitting and reflecting to the calm rippling clock, she wondered for how long? For five winters he had been gone. He may have even roamed, she thought, as far east as Sarkadon.

For his delay this time was unlike him. He was exact as a woodsman. It was Kúlluvía who taught her how to make her own bow, how to carve arrows, how to keep her breath in time with the breeze, loosing shots only when it whispered in her ear, as if it were dreaming of death, carrying the hiss of violence, into silence. “Pull the string until it tugs back at you,” he would say. “Feel the arrow’s feathers stiff in your fingers. Breathe in and hold your breath, as if you are keeping all the winds of the world in your chest. Ask forgiveness. Pray. Then let go, and listen.”

Pray. Let go. Listen. Those were commands that she returned to more than just with her bow. When she prayed, where did she go? Far off, deep inside, to the afterlife and the afterglow: moonlight, rivers, the cave, fires, smiles, laughter, grumbling, whispers, silence. All those things and more. But not how to die.

“If you dwell on that,” her uncle said, “You’ll freeze and the arrow will never find its way home.” For survival was hammered into the arrowhead, he said, imprinted and burnished into its steel and deadly point. Hers were in the shape of birds with beaks and two eyes, one half shining, the other inset with soot. It was a reflection of day and night bisected by a ridge that guided her aim: hawks, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, harriers, falcons, kestrels, eagles, loons, owls — all gliders, divers, climbers, strivers, crooners, rangers, avengers, savagers — ready to alter fate.

“Honor the dead,” he would say, “And savor the blessings of the land. Someday the hunting may stop, but who can say will starve on that day, until the ice relents and lets us raise the living from the earth in plenty again. So keep your eyes and ears open, guided by the assassins in the clouds and gliding in the wind.”

She listened closely now to the wind over land outside. It whistled high against the sun’s path and trembled the dew sitting on the window glass. It was time. She got up from her bed and walked to the chamber door, opening it. There was snow at the doorstep and off in the meadow, melting and quenching the thirst of the grass, soaking into its dark soil. The morning sun warmed her face as the wind wiped her brow. The flying squirrels had taken up in the giant pine trees at the edge of the path from her waiting place, plunging from the Uplands.

She had been waiting for the first full moon of spring, when the wizard and the witch would begin her shamanic training, drawing the fates with the threads of the ancient oracles, casting inquiries into the unknown. That’s why the skipping star had struck her. Maybe it was what they called the Deep Sign that the world was tipping over and under but on a straight line. Or was it just a star on its way to the underworld? “No one knows,” the shawoman often said. “No one.”

By which the witch meant: find out. But there was also a double meaning, or two. There was the question of knowing oneself, yes, but of knowing the spirit at the heart of all things too. For perhaps the arrow she did not know, she was taught, was simply destined to go somewhere no one can know. Still, she would go.

A hawk flew overhead, catching the wind. There, she thought, was an arrow. Grabbing her bow and her quiver, she checked her arrows’ fletchings and pulled her bowstring taught, tightening it just so, right up to her eye and the top of her cheekbone. She pulled out her hunting knife and wiped it on her tall leather boot, sharpening it in the light. She kicked her spear from a pile of firewood up into the air, its wood pole bending and vibrating, until she caught it with one hand in one quick stroke. She checked its long steel flared tip for any chips. It sparkled in the morning light. She stuck it in the earth, hiding its gleam in the mud, masking its sting from wary eyes.

She took a few slow steps forward, her boots seeping into wet dirt. Where would the signs lead? The hawk right then cried overhead. She stopped and looked up, watching as it circled and drifted in the air. What did it see? She listened to the quiet drum of waterfalls far away. The infinitesimal clicks and ticks of time melded with the sounds of creaking branches, chattering crickets and snow melting in drips, all flowing into the efflux of the meadow stream.

She turned and looked back into her chamber, and saw the prisms’ glimmers fading, and closed the door behind her. Then she turned again to face the day. Great pines, cedars, firs and oaks towered before her, reaching up into a blue sky scattered with cold bright clouds. Stepping toward the forest, she grabbed a long-hafted wood axe resting in a tree stump. A cool breeze ran through her long dark hair. Her bow’s name, Valmryn, the “dream killer,” heralded the hunt. Yet no dreams but nightmares, she prayed, would she banish from there.

For up here, she dreamed of dreams within dreams, within dreams, within dreams, of stargazing from the world’s watchtowers, smiling at the memory of a meteor skipping like a stone on water, lighting up the hills in bright waves. She was an arrow of fire shooting high, she thought. Then gone, forever, in the sky.

Over the ridge along the Magistrad, hanging over the steep and deep basin below, was a labyrinth of canyons and ravines and outcrops amid hills of green grass and ice cold streams. The hawk she saw high up scouted and weaved into the riddled rocks, where she believed must lie its hidden quarry. So she followed him. The morning had passed and now the sun shone clear and bright close to its zenith, warming a land beset by ice winds pounding from across the great river gorge where the mountains held back the eastern and northern fronts.

Whirling from the ways of the ice age, even the seasons buckled and swayed. Any day now, she thought, Kúlluvía would come round the sentinels’ gate far up by the glaciers under the mountain tops and return home. For the thought crossed her mind many times, as she followed the hawk hours after the noon. There was no telling what she would find. The further she went, the more she felt Kulluvía’s absence. In the last year, the whole world seemed afoot. But few wandered to Irèlia, their homeland, or could weather the Razakuzan Hunt.

Finally, the hawk turned east as the sun westered, gliding above a rift of granite in the Eskers and the Uplands’ serpent kame that ran south from a massive moraine of gravel and glacial grinding at the northern tail of the Magistrad vale. The bird of prey might soon disappear behind its vast walls, she thought. She hurried but kept her footfalls light. Emerging back out of the forest and cutting through big grassy corries, she came upon a rushing stream that was gushing forth from the rift. She had been there many times, but not with the water so strong.

Hopping along its southern side, she continued along the watercourse until she came up to the ravine’s mouth, then stepping onto a series of boulders, made her way up across the stream to the rift’s northern face. She could no longer see the hawk. She listened as she scanned the water for any pools or signs of fish. There were none. The rift had recently widened through some cold force of the winter, she believed, opening another path from the main course that ran opposite from the cliffs that fell into the Magistrad. She listened to its deep drum as she heard the hawk’s cry echo off the winding walls of the little canyon. The sound of the echo had sharp and lower tones that broke asunder into smaller echoes that moved at differing speeds. It sounded like laughter over the moraine.

But the overtones of the echoes told her that the rift was deep and long with many recesses and side channels below the red-tinged drumlins she saw beyond. There was a clearing up ahead through the narrow cut in the hill, inside the canyon, where she had never gone. But how would she get there?

She looked more closely as her eyes adjusted to the shadows inside the riven rock, where she saw a fracture that ran from the lower depths of the passage and up to the heights. She decided she could not take her spear with her as she climbed, so she fixed it against a boulder and the wall to aid as a step in her descent when she returned. Putting her axe into her belt, she took a deep breath, closed her eyes, and leapt.

Her fingers touched the lip of the wall’s scar, and she gripped on tight, letting her body hit and hug the rock face. She moved her legs slowly up and down until she found a crack she could wedge her foot on to rest, then she pulled herself up until she could straddle up onto the ledge. Taking a breath, she kneeled and dusted off gravel from her hands and knees. Standing up, she edged her way along the vein, following it slowly toward the top. Below her, the water loudly rushed, cutting its way through jagged and sharp fissures. Don’t fall, she thought. Don’t rush.

After making about a hundred steps, as she moved carefully with her back against the wall, she began to hear a sharp tapping. It had a funny pattern to it: twice, then thrice. It sounded like a rock being tapped against the rock wall. She stopped, and then it stopped. How strange, she thought, was she being watched? Pulling her long axe out of her belt, she slowed her breathing to silence. She took in the air through her nose to see if she could smell anything. But she smelled only the damp rich air of the wet riven granite. Then just as she was about to continue stepping, the tapping started again.

It was the same pattern, but slower this time, tentative, and with longer pauses between the twos and threes. It didn’t sound like a drip. It wasn’t a contraption. No. It was being made by an animal or by someone. She decided to wait again. The tapping kept going. Maybe it was just a squirrel cracking open a chestnut, she thought, a musical squirrel with a keen sense of time but a loose touch.

After a time, she resolved to keep moving. She had her axe handy, she reminded herself, and she knew how to cleave any animal with one swing. As she got closer, the tapping grew louder and more peculiar. It was definitely a rock, but it was being struck at slightly different angles. The tapper was imprecise, or very precise. She simply could not place it. Not a woodpecker. Not an otter.

Now she was right up to it, but it was above her, and around an outcropping in the rock face, perhaps a hundred feet above the meltwater. The top of the ravine was also very near now. She could feel the mountain air across the vale seeping over in big draughts of cold. Looking north, she could now see the tip of one of the glacial mountain peaks capped with snow rearing its rugged silhouette, jutting into the blue sky. Right around the corner, she could also now see the rock face gave way to a recess, that looked to her like the bottom ledge of a stair.

The tapping continued as she crept, and a few small pebbles crumbled and rolled over her head down into the crevasse. Was she afraid? The rushing water and jagged rocks below would kill her if she fell. Whatever it was, it was probably harmless. And yet, wolverines lurked in these hills, and mountain lions. She meditated one more time before she looked.

Even if it were a cub, they had the strength to push her over the edge if they toppled her from above. Taking a deep breath, she thought of the skipping star again. Follow its grace, she told herself. Follow its speeding destiny. With that, she swung round the outcropping and into the recess with her axe ready.

Everything exploded. Gravel flew in her eyes and face, as she saw a blur of black and blue and green dash away from her and up over the rocks. It looked like a buzzing of wings so fast she could feel currents of air whip against her cheeks. Her eyes barely caught its form. It wasn’t a flying squirrel or bird. It was the biggest butterfly she had ever seen, she thought.

Or not seen, because she couldn’t be sure what it was that she saw. She let out a quick chuckle of relief. Even if she was wrong, whatever it was, she could tell it wasn’t out to kill her. Perhaps it meant to deter her, but not through force. Once she regained her wits about her, she saw that in front of her were stairs hewn into the granite cliff. That was just as peculiar. She had never heard of any stories or rumors that people once lived here. Though the Haarynns, the cat people, were just on the other side of the forest and the valley, to the north and the west.

No time to wonder, she was after that butterfly. Leaping up the stairs, she emerged onto the shelf above into tall grass waving in the wind. The sun was bright and the drumlin hills beyond were covered in splashes of red orange, a great band of poppy flowers, thousands upon thousands, blooming underneath the cold grey and white of the mountains and their glaciers. It was the clash of spring against winter. There was a little respite coming and life returning.

So where could that butterfly be? She quickly scanned the ice-delved land. She didn’t see it at first, but then she caught it in a blur hovering far away over the grass toward the flowers, just the faintest flutter of blue, with flecks of red and green flames on its wings. Off she ran through the field.

As she came up on the tapper, they both came near to the flowers. The air was fragrant with the poppies’ sweet scent, mixed with a dreamy smell from patches of lavender, which were also in bloom, their small purple flowers peppering the vast expanse of orange and green that now grew in her mind as even bigger than it had first seemed. It was as if they were in an upside-down cloud. The butterfly was almost in her grasp, but now she noticed it too had changed from what it first appeared. Something was very strange about the little specter.

It was as big as her hand, and its body was peculiar. They waded into the cloud of petals and pollen and lavender plumes. She noticed there were other flowers here too. There were sunflowers, orchids, dahlias and lilies, and near the ground, soft velvety lamb’s ears. Bumble bees and dragonflies flitted about, working and droning. That’s when she noticed her friend had a fur collar and a wingspan flapping down, tucked into a tent-like cloak, cutting the shape of a rhombus. Diving into a cluster of butterflies, he briefly disappeared among them.

She might lose the butterfly here, she thought, so she slowed so not to scare him. It landed on a lavender stalk, then jumped to a big lily, where it went gently still, the flower bending back and forth with its weight. It scrunched up, leaning into its cup, its wings folded up, so to hide itself modestly among the lily’s core of stamens, stigmas and styles, which was an ornate thicket of reds and yellows.

Was it playing dead? She took slow steady breaths, and kneeled in the thick lamb’s ears and grass, and then gently leaned forward and moved her right hand up the lily’s stem, and with her left hand moving her fingers over leaves, shooing the other butterflies away in whirls of orange reds and splashes of vibrant blues. Patiently, she cleared a path, calmly raising her hands to trap him, the many morphos and monarchs flitting or crawling off, his vorpal form emerging.

“Don’t you have a clue?” she suddenly heard. The voice was small yet deep, as if it came from the shadows and the creases of the grass and the flowers and their flowing dance. She was astounded. Her hand suddenly trembled.

“So you came all this way only to wait and hesitate?” said the voice. The sound of his words echoed through her as if ripples in a pond were expanding out into her mind. The flower and their petals, the ears of lambs, the stalks and the leaves and the grass, seemed also to expand, growing longer and wider around her. She felt the breeze more strongly so that it felt as it grew and withdrew, a gale and a sigh and then up again, a great ocean of time pressing through.

What was big and what was small mattered not. Only the idea and the thought. She heard him chuckle, not derisively but quizzically: “If you’re going to swat me or capture me, then try your luck and let’s see how things go for thee.”

“Why, no-no-no!” she stammered. “I don’t want to hurt you! Not once or twice or thrice. I simply heard you tapping, and I didn’t want to be surprised. But now I surely am bewildered, by many, many times. My good sir, what are you!?”

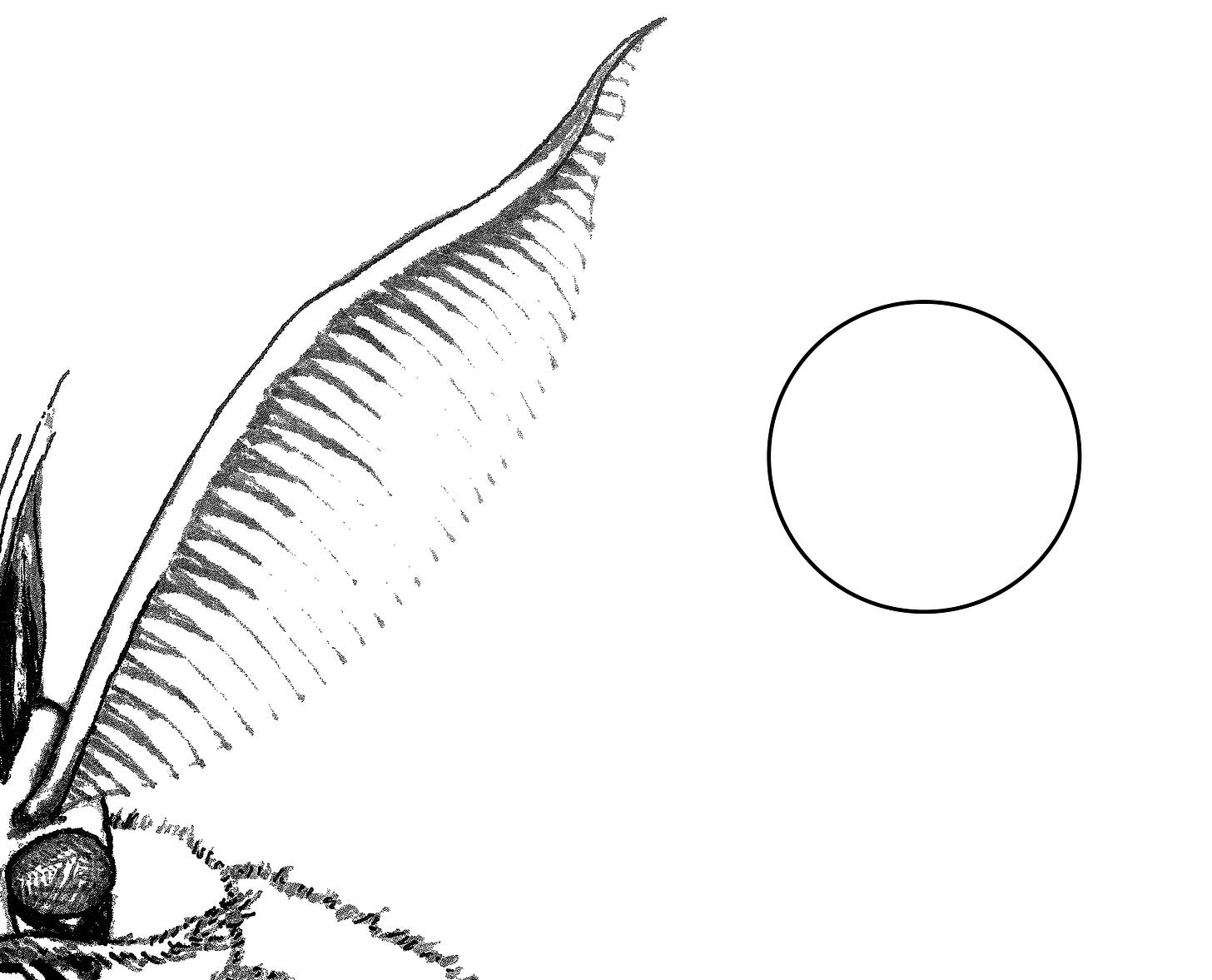

The winged thing turned around now and unfolded his wings like a flowering cloak rimmed with the finest fur in a wide cowl. She could see now that he was mostly black and shiny like many insects, with a body like a man, yet still insect-like, with spindly hands, lithe legs and an ornate torso, covered in intricate pieces of obsidian armor and holding what looked like a long thin bee-striped lance wrapped in ribbons of intertwining jet and ivory tinted with massicot.

He had a head and a face with a sharp sloping nose, and what looked like a mask and visor, with a fantastic mustache that swept across his cheeks and over pointy shoulders, two big dark green and dark blue iridescent eyes like those of a bug — eyes within eyes — and high feathered antennae that lashed up like great antlers above tall blades of green hair that formed a fin atop his raven crown. And hanging from a belt was a long wind-pipe and a curved sword. His wings especially dazzled the eyes, a mix of streaks and blotches, and both cool diaphanous and warm delirious hues. She realized, staring at him amid tempestuous butterflies, that he was a mothling — a Grand Moth.

“Why ‘who’ is more exact, my friend, for I am Halk, Halk Feleran,” he said. “My sacred name is Halkjavyk: Kijaromôn in the ancient tongue of Kirrann. I suppose you might call me a dreamer, as I can see and think far ahead like you. I was first tapping to break open a nut for lunch, then to see what musical echoes that might come out of the Riverland, because I heard someone jump to the wall path, and it turns out it was you. But I did not expect the axe, or the dagger, or the bow or the attack. Together it was more deadly things than I’ve seen in these parts since days of old, when the Haarynns once ruled here after the bitter cold.”

“Halk-ya-vik,” she said, sounding out his name. What a strange sounding name, she thought. “So Mr. Halk, the Haarynns made those steps? And, pardon me, but I must ask again, what are you?” There was silence. She was in awe of what she was hearing and seeing, so maybe time itself had simply come to a freeze. “Have I gone mad?” she asked suddenly in a panic. “I don’t recall getting sick. I have no fever. Perhaps I breathed in poison pollen from these flowers?”

“No, no, I am not from your imagination, I am sorry to disappoint you,” he said with a chuckle. “I stand apart, my lady. I would fly this sky whether you were here or not. I am a Jasper Moth, my dear. The Haarynns called us the Aikyrrie. We call ourselves the Ovyrrakrúsk. That means Dream Keepers. Halkjavyk means ‘Moon Wise’; but on a shadowed new moon, I become Myrkjavyn — that means ‘Wraith Moon.’ I have always loved the Moon and know its beguiling phases like the bug shapes of my own wings and hands. And no, the Haarynns did not make those steps. No one knows who made them.”

“So that’s a mystery even to you?” she asked. “That is strange. And dreams? Good dreams? Bad dreams? Do you have a jar or bag full of them, and how do you catch them if you’re the Keepers? Why do you keep dreams, O-veer-ra-kroos-k?”

“Very good. You have a good handle on uttering. Well, I suppose, beekeepers, we’re not unlike. We tend to the dreams of all living things in this cool carved land, helping them grow when they sleep, so they know where to go when they don’t. Sun-bright dreams. Inky black ones too. But that takes lots of explaining. Do you have a thousand years? There is no jar because dreams can’t be trapped, my lady. How, is a secret. And yes, we do not know who made the stairs.”

“I see. So the stairs were there when you came? I was hoping you would know, for my people have always wondered about such things. But keeping the dreams and what it means sounds marvelous,” she said, realizing that Halk spoke with a tone that seemed to come from the Earth itself, ancient and forgotten. “Are you old?”

“Well no, not really I don’t think,” he said. “At least not in Ovyrrakrúsk years. I have seen over one hundred thousand, thousand springs, if that’s what you mean. Most creatures your size are just children to me. Except the Elves and the Kirrai. Oh, and the dragons. Oh, and trees, tall trees. But all of that seems to be coming to an end. The sky is odder by the day, haven’t you seen? And I say that, having seen its worst days. Lightning strikes from nowhere. Fires burn the woods to the south. Glaciers drain their cold. Avalanches keep crushing everything below.”

She furrowed her brow and looked up at the ice world and spotted the ablations. The ice wall north of Othuar was calving. She had heard that the ice-dammed lake above Baugaon was flooding the tarns of Haar. And many snow-bridges in the upper passes had caved and dropped several caravans to their deaths. He was right, things were rapidly changing.

“Oh no, no! I see you’re worried,” he quickly said. “I said ‘seems,’ not ‘is.’ Like I said, children, too eager to bear the world’s cares. Don’t be so alarmed. We’re not coming to an end. Not yet. Not yet! There is still too much to do, my friend, and too much to see. It’s my job to record all of this history. I watch everything like a hawk, like a moon.”

She thought deeply about his words. Some of it sounded like nonsense. But there seemed to be a rhythm to the mysteries of this curious mothling. History was ever-changing, from day to night. But the ice was encroaching and sliding down from the mountains. Her traps were empty and it rained incessantly. She looked up at the wind blowing snow high into the sky. Halk watched her closely, seeing her drift into thought, trying to understand everything he was saying, catching and pulling it all together like leaves in the wind, and doing it fairly well, he judged. He could see it in her eyes: not just worry, but prophecy.

“Well, Kyrraskala!” he said, using one of his favorite phrases to break the silence, and pointing his lance to the sky. “That means ‘lightning in my head’: a thunder-stick is a staff we craft, and at the end pack various fire powders, like a long torch. Because this is no ordinary day, I thought I might say. Did you see that amazing meteor last night?”

She looked at him. Her eyes widened, then focused on his eyes, which showed no emotion, no irises, no opening or closing of lids or pupils. He had no pupils. Her mouth slacked. “Yes, I did,” she answered quietly. “Keer-ra-ska-la?”

“Yes, that’s right. Brilliant bright luck, that! Lit up the trees and the mountainside bright as day. It reminded and re-minded me of the Great Tempest before the ice age. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. My lady, what is your name?”

“Greil,” she said. “My name is Greil. In my native tongue, it means Sable.”

“Greil,” he said, leaning his head forward with his hand moving to his chin, serious in thought. “I like that. It’s strong, and supple. Sable is good too. That fits your hair. Sables are also quick witted creatures, my dear. You could use a controversial epithet, though. I’m sure we’ll find you one.”

“Thank you, my lord,” she said, and bowed her head before the lily and the mothling. “That is most kind of you. Controversial sounds fun and intriguing. I must say, I am greatly enjoying your company and our chance meeting.”

“I wonder,” he continued, as if what she said was an indisputable fact, not a charity or a flattery, nodding his head to her polite bow. “Have you met Lord Beetle? He’s dark too, and fabulous. I suppose you would enjoy his company just as much as me. His court can come to you.”

“I have not. Who is Lord Beetle? And how do you know I would like him?”

“It’s not because you like me, which I can see. It’s something else, that I really shouldn’t say. But you can’t miss him, or rather you certainly can, but you shouldn’t, and that makes him all the more fascinating, if you follow?”

“No, I am sorry Mr. Butterfly Lord, sir. I do not follow.”

“Well, I am a lord of butterflies, you could say, and a Moth, older than the cocoons that first graced these hills. The night is my domain, my dear, and I came from another world. For it is good not just to follow, indeed.”

The sun was now entering dusk and the shadows were growing deeper and longer. He shook his thunder-stick in the air and she heard a rumble rolling over the hills and the Eskers, as lightning flashed in the clouds over the mountains far off. Two purple and violet flames burst at both ends of his lance with silver sparks that lit the edges of the leaves and grass, illuminating the lily in which he sat. The fierce flickering of his fire-staff shimmered in his eyes within eyes, and danced against his exoskeleton of obsidian, playing in the shadows of his moth wings, a cloak of narrows, blots and dots, suggesting a map to the otherworld.

“Kyrraskala!” said Halk once again. “Things are changing, Greil, not just the Sun and Moon that always circle round. That is the lesson of Lord Beetle. Aratarasu, we call him, the Master of Dreams, the Cloud Beetle, the Walking Gem. Though he gleams like the most beautiful star, he lives underground in shadow. He comes out in storms. All kinds of storms. He is there, and then he is not there.”

“A-ra-ta-ra-su,” she repeated slowly.

Thus concludes the first chapter of the Aphantasia Trilogy: Where No Thoughts Go, an original fantasy work by T.Q. Kelley. You can read about its mission and musings here. We will be self-publishing future chapters to book one, The Low Owl (most will be free), and short stories (which will be for paying subscribers) here at Wraith Land.

Copyright owned by T.Q. Kelley.

Love the rippling echos of time/space/thought/dreams/reality. Great start - looking forward to more chapters.