The Mixed Heritage of Tolkien's Myth

Part One: How the stories of Lúthien and Kamala flipped expectations

What does Middle-earth have to do with Kamala Harris? As the world wobbles on its axis, heroes and villains come into play from across time and place. But it’s the dreamers who cast the strains of mythic memory, who make works of art that fire the dramas of future dreams. Taken as a whole, the works of J.R.R. Tolkien are progressive even for our own time, even if some of his more conservative views still go against the grain. Division and hatred blazed through Europe for much of his own life. He witnessed and endured war, poverty, tyranny and bigotry. His answer was emphatically chivalry, decency, honesty and love.

Tolkien the dove? This is essentially the thread that runs through Tolkien’s mythology, and while it is at the heart of the story of Frodo and Sam and Gollum, that moral intensity was first idealized in Tolkien’s Beren and Lúthien, one of the three great tales that form the symphonic literary arc of The Silmarillion, a multi-generational journey through darkness into light. Its story is essentially about the mixed heritage of heroism, across genders, and across diverse genealogies.

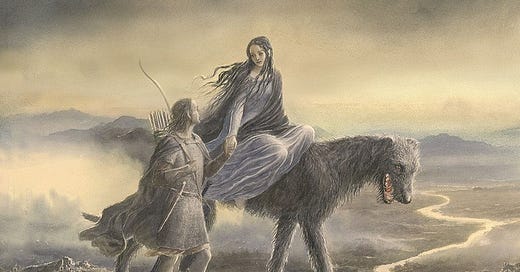

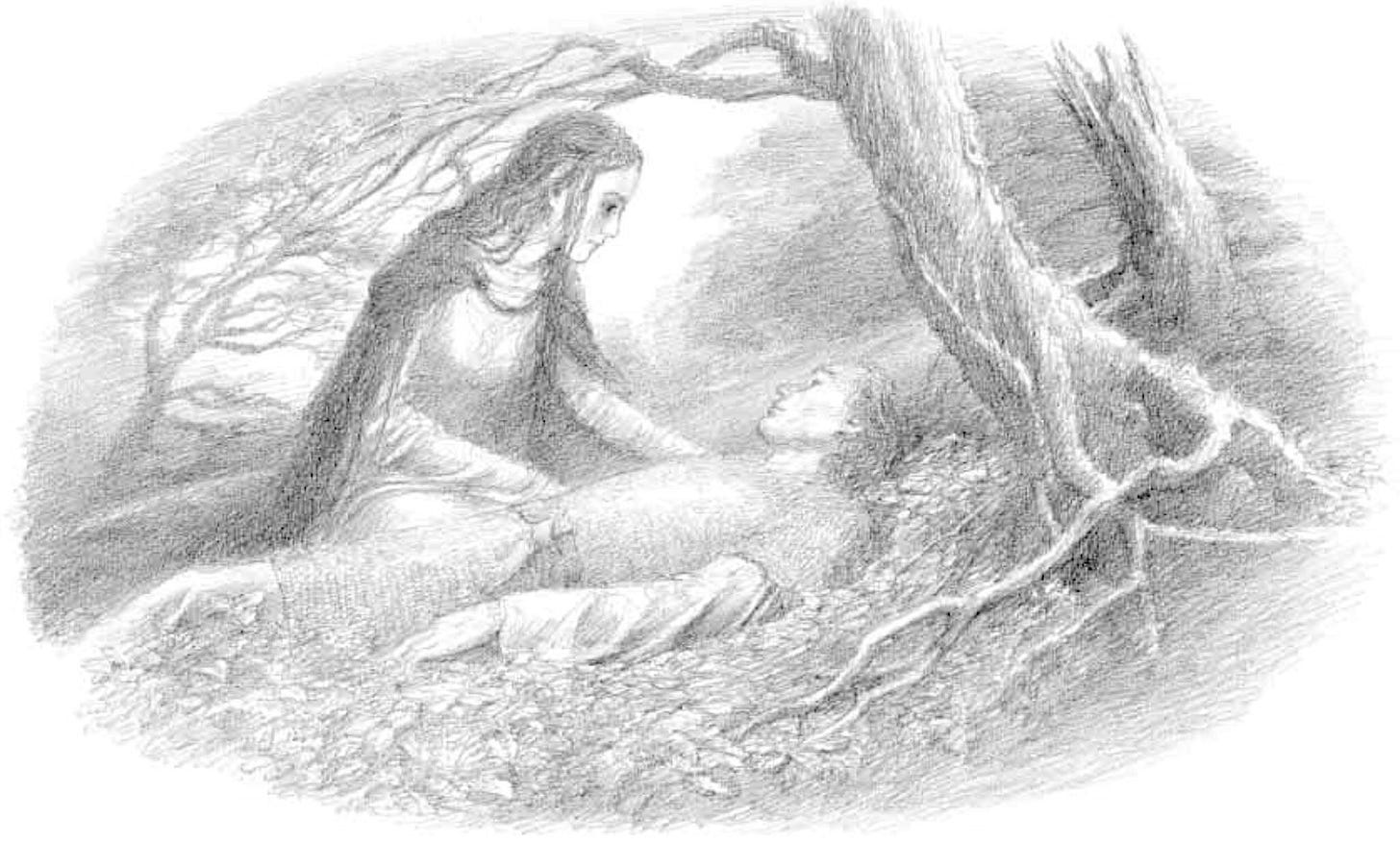

The character Lúthien from Beren and Lúthien is core to that narrative of empathy and bravery. She is the daughter of an Elven father, Elwë Thingol, and an angelic mother, Melian the Maia. Central to his mythology, Lúthien falls in love with a human man, Beren. When the man asks Thingol for her hand, her father refuses. Thingol says he only will let them marry if Beren goes into the dungeons of the dark lord Morgoth and steals one of the great jewels for him, a Silmaril. It is on this impossible quest that Lúthien rescues Beren when he is captured, and then helps him infiltrate Morgoth’s lair. Together, Beren and Lúthien have a son, who in turn has a daughter, who marries another multi-racial hero, Eärendil.

[Read our “10 Ways Tolkien Ladies Outdid the Men” and if your fan, share your own favorite female moments and characters from Middle-earth in the comments.]

It’s not hyperbole to say that Lúthien saves Middle-earth with Beren. Their story of redemption lifts up the free peoples in their great struggle against Morgoth after a major defeat in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears. It is her grand-daughter Elwing and her husband Eärendil who then help win the war. Of course Kamala’s story is still yet to fully unfold. But her inauguration as the first female Vice President in the United States, and her mixed Black and South Asian heritage, mark a historic moment that invites the Lúthien comparison.

Lúthien is also perhaps the first multi-racial heroine in any great mythology. Together with Kamala, they have formed a kind of archetype that deserves its own unique considerations. Not only are they breakthroughs as women, but they are women of multiple ethnic or racial backgrounds. While Lúthien is ultimately “white,” what she achieves with Beren is still groundbreaking. By challenging negative norms, they overcome bigotry and apartheid through love.

The Arthurian tale of Tristan and Isolde is also a probable influence, where a love potion gets a knight and a maiden into a perilous love triangle, with underlying echoes in another Tolkien story — The Fall of Gondolin. The human hero Tuor is welcomed by Turgon, Elven King of the great city Gondolin. He favors Tuor and blesses his union with his daughter Idril, while Idril’s Elf cousin Maeglin jealously tries to foil the kingdom, eventually betraying its secret location to Morgoth. But after Gondolin falls, Tuor and Idril’s multi-racial son, Eärendil, meets Elwing, and together they sail for the land of the gods to seek their help in the final struggle of The Silmarillion.

Tolkien presents clear counters to damsel-in-distress conventions. For one, Lúthien is never in the same kind of distress as Beren, except when he dies. For the most part, she is the one helping him out of pickles. Second, the DNA of the story is based on Tolkien’s own life. He saw action on the Western Front in World War I at the Battle of the Somme, where he lost two of his best friends, and was then sent home with debilitating trench fever. It was there, reunited with his wife Edith — who his parental guardian had forbade him from seeing until he was 21 and whom he married just before he shipped off to war — that she was able to raise his spirits and bring him back out of a dark depression. The two had first fallen in love as house mates when they were orphans. So there are a lot of lived tribulations and triumphs reflected in the story of Beren and Lúthien.

Scholars Janet Brennan Croft and Leslie A. Donovan explore all of the complex angles of Tolkien women, and how and where he either succeeds or falls short in advancing female identity, perspectives and causes, in their book, Perilous and Fair: Women in the Works and Life of J.R.R. Tolkien. Everything from his own personal investment in his female students and pupils — which was remarkably strong but also colored by his own inability to perceive the glass ceiling that most would suffer later in their careers — to how he elevated female roles in his earliest fiction, is explored in detail, and presented in a larger context of growing scholarship around questions of gender and feminality.

So while not always at the center, Tolkien crafts critical roles for his women. There is Arwen, who is directly inspired by Lúthien. She does not go into danger like her predecessor, but she spiritually guides Aragorn and defies her father from dictating who she will marry. There is Galadriel, who advises the Fellowship of the Ring after they have lost Gandalf, and gives Frodo the Phial of Galadriel, which ultimately saves the quest. Her wisdom permeates the rest of the story. There is Éowyn, again, a “courageous leader,” who rides into battle and saves Minas Tirith, and by extension, the whole quest. There is even the she-spider Shelob, who features as the most thrilling and unnerving monster in all of Tolkien’s fiction. Even if she is not the most powerful, she is the most unforgettable and fully realized.

And then, there is The Silmarillion. Lúthien has perhaps the starring role in the whole grand scheme. It is her love that ultimately inspires Tolkien’s mythology. Her grand-daughter Elwing sails with her husband Eärendil to win the succor of the gods. There is Haleth, the legendary chieftain of the Haladin. And then there are the Valar and the Maiar — the gods and the angels. Among them, many of the greatest are female spirits. There is Varda, goddess of light and the stars. There is Yavanna, goddess of all growing things. There is Vairë, who weaves the story of time. There is Nienna, the Lady of Mercy. There is Nessa, swift as an arrow. And there are many, many others in the rich mythology of the “First Age.”

But Varda is the most crucial. It is she that the Elves of Middle-earth worship the most and call to in times of trouble by her Sindarin names, Elbereth Gilthoniel. She’s the one who ignites stars and captured the dews of the Two Trees of light — created by Nienna and Yavanna — that shined across Valinor, their work of life and water providing a mixing of silver and golden illumination that the Elf smith Fëanor captures in his three gems, the Silmarils. It’s not just that Varda, Nienna and Yavanna’s light animates the whole mythology of Tolkien’s “First Age,” including Beren and Lúthien’s heroic quest, but his whole Ring cycle too.

This is less well understood by readers, but it is this greater background, epitomized by the love of Lúthien and the power of Varda that provides Elves, and hence humanity, with hope through darkness. It is the star of Eärendil that Frodo and Sam invoke when they use the Phial of Galadriel to stay Shelob, and it is the same star that keeps Sam trudging during their long march through Mordor. It is Varda and Nienna who also greatly influenced Gandalf when he lived among the gods as the angel Olórin, before he was sent to Middle-earth to stop Sauron.

It cannot be said enough how much Varda, the Trees and her stars meant to Tolkien’s mythology. He was a Catholic and hence a religious minority in his beloved England. He was also forever devoted to the memory of his mother, who converted to Catholicism when he was a boy, in part because after she lost her husband Arthur when Tolkien was only three years old, she turned to the church for its charity and spiritual counsel. She would die of diabetes when Tolkien was 12; her family stopped all financial assistance to her when she became a Roman Catholic. It’s hard to say how much of Varda is Tolkien’s mother, and how much Virgin Mary is Varda too. But one can be certain, based on his own letters and biography, that their courage and memory greatly defined him.

So when we look at Lúthien, or Kamala, or any other strong female role model, especially those with mixed roots, whether illuminated by ethnic struggles or life’s countless trials, that by flipping ancient archetypes of female subservience, it is in these leaps of faith and reimagining, however unfinished, that families and peoples can change the world, and move myth into universal brilliance.