The Master of Middle-earth, J.R.R. Tolkien, struck serious luck with his youngest son, Christopher Tolkien, who passed away one year ago to the day. Christopher was often described as his father’s “literary executor.” He was an archivist and a preservationist, teasing out new gems from his father’s mountains of notes and wrapping them in his own erudite illuminations. He followed in his footsteps to Oxford scholarship, and after his father died in 1973, he edited and published 25 posthumous works by his father, securing Tolkien’s mythology as the greatest the world has ever known.

Yes, there is Star Wars, and the Marvel or D.C. Comics universes, as well as League of Legends, World of Warcraft, Magic the Gathering, and so on and so on. Yet, only one “secondary world,” as Christopher’s father coined it, came from one mind in immense and mind-boggling detail, including histories, languages (the Tolkien legendarium’s original inspiration), poetry, paintings, and three literary works that revolutionized three distinct modes of storytelling: an adventure story that would become beloved by children and even adults (The Hobbit), an epic trilogy filled with darkness and deep philosophical currents beloved by adults, young adults and precocious children (The Lord of the Rings), and a grand creation myth cycle that approximates a kind of bible for modern fantasy with deep questions about the universe (The Silmarillion).

Yesterday, January 15th, was also the premiere of Marvel’s WandaVision, a sly, almost psychedelic trip through 1950s and 1960s American television tropes that simultaneously deconstructs two mythic archetypes: the superhero and the family sitcom. The ur-blueprint of the Marvel Cinematic Universe has proved massively lucrative and creatively versatile, combining the multi-author mega projects of the comic book industry with film’s mythological grandeur, achieving a sweeping multi-sensory tableau, a Gesamtkuntswerk, that would have astounded even Richard Wagner.

Jon Favreau, who commenced the MCU with the first Iron Man film in 2008, has more recently been working his magic for the Star Wars universe, birthing for the Disney+ platform a TV streaming phenomenon in The Mandalorian. Working with Dave Filoni, the animation director behind The Clone Wars, Favreau is now busy extending the SWU into new titles, one around Filoni and Lucas’ she-warrior Ahsoka and another around scouts and protectors of the emerging government following the events of The Return of the Jedi, called The Rangers of the New Republic. With few details released so far on either story, it’s still a safe bet that Rangers may very well take a page from Tolkien’s Rangers of the North, i.e. Aragorn and the Dúnedain. Lucasfilm also announced a book publishing blitz in parallel around the previous Star Wars republic (pre-prequels). James Waugh, VP of Franchise Content and Strategy at Lucasfilm, described this new slate, Star Wars: The High Republic, as “vast interconnected stories over multiple years.” They have invited a host of writers to take on the challenge.

Similar to how Favreau approached Iron Man, these various extensions of George Lucas’ original vision appear more greenfield, deliberate and detailed, than the initial film run of the Disney era of Star Wars. Favreau grew up playing Dungeons & Dragons and has credited it for helping shape his world-building instincts. Part game, part storytelling, the ur-RPG franchise has enjoyed a major resurgence in recent years among its first generation converts and younger adopters. It’s even getting its own film franchise reboot at Paramount, with actor Chris Pine set to star. D&D is owned by Hasbro, and the emerging influence of merchandise in today’s “multi-verse” content wars is never far off. Toys are even playing a direct role in TV animatics these days: Director Robert Rodriguez used them as part of his pitch for The Mandalorian battle scenes in Chapter 14 of The Mandalorian. The Show-runners Favreau and Filoni were not only amused by Rodriguez’s low-tech solution in a high-tech enterprise, but for them it certified his geek credentials.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, I clearly remember the atavistic power of such figurines. My G.I. Joe and Star Wars action figures were foundational experiences. Han Solo in Hoth gear, a scuffed Boba Fett, ninja-like Snake Eyes and Hiawatha-like Spirit were favorites. Dolls have been a part of humanity since at least the 21st century B.C., four millennia ago, accompanying the deceased into the afterlife in Egyptian tombs. D&D has used miniatures as part of its gameplay since its early days, and table-top games like Warhammer have taken this phantasmal strategy to the extreme. My own fond memories extend back to my aunt and uncle buying my brothers and I the pewter set of the nine heroes of the Fellowship from The Lord of the Rings (Grenadier Models) at a Pearl City mall in Hawaii circa 1985. Tolkien’s stories and mythological detail were key ingredients to the original conception of D&D and many of these physical incarnations. Gary Gygax, who co-designed the RPG, later played down its influence due to copyright disputes with Tolkien Enterprises, but in 2000 more publicly admitted its long shadow over his own mythic dream land.

This blossoming of mythological mediums was in no small way anchored in Tolkien’s commitment to making the fantastical palpable and present. There were many other giants who helped usher in these pastoral past-times, from Edgar Rice Burroughs to Walt Disney to Atari and Nintendo to Michael Moorcock and his Elric of Melniboné pulp fantasy book series — he grated against the long shadow of Tolkien, taking an antagonistic attitude in his youth, but once again, admitted grudgingly in later years the fantasy master’s positive importance.

Tolkien’s lovingly detailed descriptions of everything in his Middle-earth and its polyrhythmic élan is still unmatched today in the literary arena. Frank Herbert’s Dune comes close in terms of ambition, but lacks the lyrical power of Tolkien’s writing. From describing Legolas’ attire and abilities — the elf walking on snow stands out for its grace and clarity — to unfurling the magnificence of Shadowfax, “lord of all horses,” Tolkien gloried in the sight, sound, texture and endless possibilities of words.

On the one hand, he elevated detail as one of the key pillars of any truly immersive fantasy work into what is called “world-building.” From theme parks to massively multiplayer online role-playing games (termed nowadays as “open worlds”), the dynamic of detail emerged naturally in well-off modern societies as a result of increased leisure time in the post-industrial era (after the difficult trials of two world wars). But Tolkien gave that detailing not just incredible energy, but high moral purpose, attaching it to deeper spiritual concerns. On the other hand, he explored that detail through three radically different approaches, establishing another key pillar in his world-building: expressing his “secondary world” in different styles, including mediums. In this, like George Lucas before George Lucas, he was a great experimenter. Distinct from Lucas, however, Tolkien tinkered primarily alone.

In retrospect, this is why his achievement was so immense. He had C.S. Lewis and The Inklings literary club cheering him on. He had his family as an early audience. He had more time than most, with his relatively secure professorship at Oxford teaching Anglo-Saxon — he was no slouch in this department, however, as his epoch-defining essay on Beowulf, “The Monsters and the Critics,” demonstrates. It’s still cited today as a watershed moment, transforming Beowulf from a merely “archaeological” concern to a highly artistic one. Even so, the scale of Tolkien’s mythicism required a remarkable wheelhouse of invention that whirled tirelessly in the intellect of one man.

This brings us to the next key pillar in his mythological strategy. If the first can be described as Hyper-Detail and the second as Hyper-Variance, then the third is perhaps best summed up as Hyper-Personal. This isn’t just in terms of Tolkien’s learned, highly English voice, informed by an internalized Catholic ostracism. It’s in his commitment to his vision, one that at the time was frowned upon by many, especially those in his own literary caste. He once said that if he wasn’t careful, in certain contexts, people would think he was a loon when he talked about his Middle-earth. And yet a loon he was in the best sense of the word.

His vision was highly unique when The Lord of the Rings was published in 1954-1955, and it remains so. Much of its power came from its authentic weirdness. It was simply Tolkien being true to himself, with the skills to back up his instincts. However, it was far from easy. It took him 12 years to write. Not only was he intuitively working out very complex story architectures and systems, but he was bringing its alien reveries into harmony not only with modern times, but with the past and the future.

How did he do it? We know a lot about how he did it thanks to Tolkien’s biographers, various scholars, and especially thanks to Christopher Tolkien’s exhaustive 12-volume series The History of Middle-earth, which excavated almost all of Tolkien’s various unfinished manuscripts and arcana, including early drafts of The Lord of the Rings. We know that it took him decades of work, starting essentially during World War I.

Books also have a more expansive effect on the mind. Movies and video games are highly “visual” in that they show us a story unfolding in “real time.” However, a fantasy book is just as visual, if not more so. No two people will literally “see” or “hear” a fantasy text the same way. Words give far greater mental space to the imagination, not just between letters on a page, but between the varied symbols representing sounds, memories and images that form the meaning of words, and hence the imagistic pictures writers try to create. Tolkien even created his own letters and scripts, such as Tengwar, or derived inspiration from ancient runes. Critically, those pictures become the reader’s just as much as the author’s.

In this way, Tolkien’s mythology is Hyper-Personal both for the author and the reader. It is a book that is experienced, more than it is read. It’s almost as if we’re looking past the words on the page into a world beyond, a landscape conjured by a magical “spell,” and one that is at once internal as much as it is external — almost telepathic — a dream cast from an imaginary fictional world to the here and now, breathing and speaking new life into a consciousness beyond time.

Language is key to this transformation. Tolkien’s Middle-earth is as much a place as it is an interface. It’s not enough to simply construct concepts or words through language. There is an aesthetic style, an identity, that must also ring true.

This is often called “voice” in writing. But with great fantasy it is more demanding. There is also a technical and percussive aspect too. In the same way Tolkien beats the drum of “perilous,” so does the Greek bard Homer pound his “wine-dark sea.” But with fantasy, and science fiction, things that don’t exist in physical reality also need names, which are then repeated until they become “true.” Hobbit. Blade Runner. Jedi. They’re not lies. They’re dreams.

And while both can be shared, only one reveals deeper truths. “Lies breathed through silver,” is how C.S. Lewis once described myths. Tolkien pushed back on his friend by arguing that true myth in the spirit of sub-creation (i.e. Creativity with a capital “C” and guided by the hand of a compassionate “God”), came from a deeper source, a holy light that burned at the center of all things. In this way, one can almost say that dreams — the auto-cosmos that emits within our brains during nightly simulated death — is truth breathing through sleep and the unconscious, a light in darkness.

Nightmares also breathe from the same core. That’s one of the main points of Alexandre O. Philippe’s extraordinary documentary on the greatest sci-fi horror film of all time, Dan O’Bannon, H.R. Giger and Ridley Scott’s Alien from 1979. Titled Memory: The Origins of Alien (an homage to O’Bannon’s original name for his script), it connects the dots from ancient Greek Furies to the Vietnam War to the primal roar of a 1970s feministic awakening — mostly unconscious in the telling. The infamous “chest-buster” scene is a culmination of these forces, initially dormant in O’Bannon’s Midwestern imagination, memories of creepy cicadas bursting from the earth.

In the case of Alien, Philippe argues it was the unique combination of O’Bannon’s unnerving vision of outer space, Giger’s bio-mechanical designs inspired by ancient Egypt, and Scott’s sharp director skills, that birthed a mythological breakthrough. The philosopher William Linn gives the documentary its key framework when he connects Alien’s myth to Tolkien’s “Cauldron of Story” metaphor — from his On Fairy-Stories essay, which Tolkien wrote in 1939 early in the 12-year period that he was writing The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien averred, “Speaking of the history of stories and especially of fairy-stories we may say that the Pot of Soup, the Cauldron of Story, has always been boiling, and to it have continually been added new bits, dainty and undainty.”

Linn’s clever use of the “Cauldron of Story” is to argue that there is an underlying layer of dream, or Jungian unconscious, that artists, by luck or design — and in the case of Alien, an “undainty” mythic breakthrough by way of three unique visionaries coming together — are every now and again able to access and stir to incredible effect.

Which brings us to James Cameron, who extended the mythology of Alien in bold ways with his action horror sequel Aliens in 1986. Like a great landscaper, one reshaping the natural world (in this case Alien) into a hyper-detailed Japanese garden, he preserved the right elements that were core to the myth and combined them with more personal instincts, extending the “franchise” into new and exciting territory. O’Bannon was not involved, nor was Giger or Scott. But Cameron treated the original myth with the right amount of respect, taking pains to not change anything fundamental about their vision, writing the script and carefully crafting early concept art himself.

In some ways, the autodidact Cameron is perhaps even closer to Tolkien than Lucas. While Tolkien never did any deep sea expeditions (Cameron is an avid sea explorer), the two share a more singular commitment to their art. Not only did Cameron succeed with Aliens, but he also dreamed up Terminator and Skynet, both a great myth for our increasingly technological age and a cautionary concept worthy of the Ring of Power. This displayed considerable Hyper-Variance.

He could have stopped there, but after conquering Hollywood as the “king of the world” with Titanic, he went back to the drawing board and came back with 2009’s Avatar, one of the highest grossing movies of all time, second only to Gone with the Wind. It was in a word, epic, and contained a ton of research, not just in terms of 3D stereoscopic filmmaking techniques, but in terms of the world Cameron envisioned. This, in Tolkienian fashion, included a language for his tall blue aliens, the Na’vi, as well as an otherworldly bestiary that dazzled the eyes.

Like all fantasy world-builders, he also plumbed some novel sources drifting neglected in the popular consciousness. Case in point was the visual look of the film — floating rock islands and bright-hued Banshee dragons — which seemed to derive inspiration from Yes album cover artist Roger Dean. Fun fact, the prog-rock band’s 1974 long-player is graced with one of Dean’s best paintings, “The Gates of Delirium,” which was directly inspired by the mythic journeying in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien’s poem and phrase “The Road Goes Ever On” is particularly relevant to Dean’s own mythic mission. In an interview with Mutual Art last year, Dean explained how his love of Tolkien’s connected landscapes informed his paintings and his own hikes through Britain. Visual artists are critical partners in the extension of myth. Painters like Alan Lee, John Howe, Ted Nasmith and the Brothers Hildebrandt created iconic pictures of Tolkien’s worlds — like cartographers and “photographers” charting his imagination. Ralph McQuarrie is also famously celebrated for his inspired concept art of Star Wars — several of his paintings were key to Lucas’ initial winning pitch to 20th Century Fox and continue to inspire the artists at Lucasfilm. French graphic novel artist Jean Giraud “Moebius” and industrial designer Syd Mead were also critical in rendering dream worlds like Tron and Blade Runner.

So when it comes to Tolkien’s stories, or Dean’s art, or the fantasy worlds of many modern myth-makers, it isn’t just the Cauldron of Story that they dip into, but the Mysteries of the Land — its vastness, its topographic thrills, its sense of place, its ancient surrealistic twists. Seas never stop moving. Mountains never get old.

The land also provides the mortal context for the moral drama of any great mythology, from Homer’s Troy to the Icelandic Sagas to Tolkien’s deeply divided Middle-earth. Prophetically, Tolkien in his own way even anticipated today’s hellish climate change. His vision of tortured landscapes, choked by the smoke of Mordor or the vomiting dungeons of Angband, is awesome in its power. That the nature lover was equally masterful in his conjurings of fair lands and vistas, from Rivendell to Moria and the Misty Mountains to Lothlórien and Minas Tirith, should be no surprise. A wizard of light and shadow, his descriptions of imaginary places are still today some of the greatest special effects of all.

Every mythology gets different kinds of landscapers. In some cases, the extenders can seem more like bulldozers. This can either fail, or take the myth into new revelatory directions. On the happier path, Ridley Scott interpreted Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and transformed the book into a bluesy, soulful, and haunting sci-fi masterpiece — 1982’s Blade Runner.

Scott’s Blade Runner (the Director’s Cut that is), is arguably better than the book. Dick is a sorcerer of mind-bending concepts, like his spray can that literally erases reality in his classic Ubik. Paul M. Sammon’s Future Noir, an authoritative history on the making and legacy of Blade Runner, makes a compelling case that challenges a long held belief. Sammon argues that Scott didn’t discard most of Dick’s story but more accurately that he transformed Dick’s source material. Many of its transformations were aesthetic and visual. For example, Scott incorporated the incessant rain from his childhood in Cumberland, England. The location of the story also moved to Los Angeles. Instead of Dick’s vision of a mostly deserted San Francisco, Scott replaced it with a bustling multiracial metropolis inspired by Hong Kong.

Yet some of its most important transformations reworked the ghost in the machine. Hampton Fancher did the original script drafts of Blade Runner, which were enhanced with a “harder” and more direct style by David Peoples. The lead replicant Roy Batty’s famous dying line — “all those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain” — were conceived by actor Rutger Hauer on set; the evolution of Dick’s mythology through the digestive and sometimes acidic churning of film production is infamous in the annals of Hollywood. And while it took a decade for Scott’s far more effective cut to unlock Blade Runner’s true magic, that painful birth is part of what makes it work.

So in almost every way, the film artists working to translate Dick’s dark psychedelic vision of the future into celluloid entertainment, didn’t just extend, but transformed it into an even greater mythic expanse: They took the DNA of Dick’s ideas, and breathed their own fevered truths into his unsettling dream: a story that was inspired by Dick’s research on Nazi Germany and the inhumanity of SS guards stationed in Poland. One soldier diary entry in particular sparked his humanist conception of androids. It read, “We are kept awake at night by the cries of starving children.” He had put his finger on the darker mythic wave of fascism, and pure evil one could say. Whether we are talking goblins, Ringwraiths or heartless robots, Dick wrestled with what he identified as a “defective group mind,” a loss of empathy so profound that those who suffer from it could no longer be called “human.”

Such an insight does not only echo through Blade Runner, it reshapes its emotion by reconfiguring the protagonist Rick Deckard’s own alienation in the form of Roy Batty’s act of forgiveness. Scott flips the whole script at the end without changing Dick’s fundamental themes when the “human” Deckard learns he too is likely an enslaved android. But just like the audience at that moment, he awakens to a far deeper definition of humanity. It cuts both ways.

If Dick, who suffered from insomnia for years, was hooked into some deeper dimension of the divine, something he professed and wrote about extensively, then unlike the SS soldiers, perhaps he was in turn kept awake at night by their complaining about being kept awake at night — by the truth that one’s humanity can be hollowed out by mythic lies and hateful rhetoric. Perhaps Dick accessed the Cauldron of Story like O’Bannon, creating a new cautionary myth, while Blade Runner the film not only extended his dark mythology, but transformed his words into highly sensitive cyberpunk.

Unfortunately, Ridley Scott’s own mythic vision has not always been lucky in its mythological landscaping. The extensions of the Alien franchise post Aliens are all troubled. All of the later films tried too hard to transform the original myth created by O’Bannon. They fall short despite big budgets and talented creative teams. Visually stunning, Prometheus even had Scott at the helm, but a confused under-developed script seemed to doom the “prequel” for many with awkward dialog, nonsensical character arcs and plot twists that defied not only logic, but basic common sense. The pot of soup never comes together.

More contentious is Blade Runner 2049, which had Fancher scripting again, pulling forward some of his original ideas from the first film that had been cut (e.g. the soup pot in the agrarian outpost at the film’s opening). It had a talented cast and acclaimed director in Denis Villeneuve. But for many, it was sterile. There was no struggle in its production, which is antithetical to Dick’s addled, prescient mythology.

The modern mythos that was perhaps just as addled in its beginnings was Star Wars. The original production was a mess. George Lucas nearly had a heart attack making it. The executives at 20th Century Fox, except Lucas’ main sponsor Alan Ladd (who also backed Blade Runner), didn’t get what Lucas was trying to do. In the editing room, it all almost fell apart. Yet providence seemed to step in with Lucas’ wife solving some of the film’s deeper narrative conundrums and John Williams composing a music score for the ages.

It’s not remarked upon a lot, but Lucas was also greatly influenced by Tolkien, not just Herbert or Edgar Rice Burroughs or Flash Gordon. The very first drafts of the Star Wars script include lines taken right out of The Lord of the Rings. Ewoks are essentially Lucas’ furry version of hobbits (an admiration he would extend in Willow). A lot more is made of the influence of Flash Gordon, Japanese film auteur Akira Kurosawa, or mythology scholar Joseph Campbell, who it seems relished being Lucas’ Obiwan. Or Gandalf, as it were. Oddly, Campbell waved off Tolkien. He didn’t get it. But Lucas did. Think about it. Both wizards “die” during the hero’s journey.

When Favreau took up the baton of Star Wars, he smartly returned to some of Lucas’ original influences, but also added some new ones that emerged from similar waters. Chief among them was Lone Wolf and Cub (in Japanese: Kozure Ōkami), the samurai manga by writer Kazuo Koike and artist Goseki Kojima. It’s an extraordinary artifact filled with beguiling tales and beautiful artwork. The model of a lone warrior “taking along his child” starts here.

Favreau also channeled Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns, particularly Clint Eastwood’s taciturn gunslinger, the Man With No Name. Even the score to The Mandalorian slyly echoes Ennio Morricone’s main theme to The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. And in one more cross-cultural loop, Leone’s vision of the American West was in turn influenced by Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, anchored by the actor Toshiro Mifune, who plays a wandering rōnin, a rogue samurai with no name.

Filoni, who was the supervising director behind The Clone Wars animated series and is essentially Favreau’s creative co-pilot on The Mandalorian, has brought his own formidable talents to the SWU. I actually knew Filoni early in his career. He gave me a DVD of Lucas’ THX-1138 for my birthday one year, long ago in a galaxy far, far away. He’s emerging, it seems to me, as the heir apparent to the Star Wars empire, having apprenticed with Lucas for many years. We were good friends when he lived in Los Angeles before he joined Lucasfilm and moved to the Bay Area. I last ran into him briefly at the opening of The Force Awakens in 2015. At the time, I was the product lead for the official Star Wars App and creatively drove its interface and design — an “inside out droid” like “looking into R2D2’s soul” as I described it — so my own professional journey into the mythic space of Star Wars was serendipitous, if very much at one edge, depending on your perspective.

Filoni is now very busy helping architect the extension of the Star Wars universe. I can personally attest that he is an intuitive and gifted person and the biggest Star Wars fan I’ve ever met. I actually first met Dave in 2001 the day before the “opening day” of The Fellowship of the Ring on the Universal CityWalk. We saw the first midnight showing that night together. I was one of the first 20 people who camped out for box office tickets the night before (this was long before one could reserve tickets online). Calisuri (real name Christopher Pirrotta) — still one of the key contributors to Tolkien fansite TheOneRing.net — gave me a Sideshow figurine of Frodo while I waited in line. I think I won it in a raffle.

I can’t remember. But I do remember meeting Dave and his girlfriend Anne for the first time that day. They were mutual friends with a close friend of mine, and I had bought tickets for the group, including my brothers and some of my other closest friends. I bring this up because myth can bring people together in many interesting ways that can diverge but rhyme over time all the same.

I sense mythic truth in various aspects of The Mandalorian series, the same as I see, hear and feel it at times in the various new Star Wars films. Some fans have revolted against some of the mythic changes in these films. To them, the extension of Lucas’ vision has been problematic. But problems are good. All mythologies in progress have them. Just read The History of Middle-earth; it’s a multi-year chronicle of fits and starts.

It is my own opinion that Solo was fantastic, and yet it did the worst at the box office. I also loved The Rise of Skywalker and believe it’s the best of the three new saga films, though I respect anyone’s impassioned disagreement. It goes without saying, Star Wars fandom is a complicated thing.

Case in point, I distinctly recall a phone conversation I had with Dave after The Attack of the Clones came out. I was not a fan of The Phantom Menace, but I liked a lot about Clones, especially Obiwan Kenobi’s sleuthing on the planet Camino and his dogfight with Jango Fett. I made the case that perhaps Anakin Skywalker was a clone, and hence his immaculate conception. As a child, I was fascinated by Obiwan’s mention of the “Clone Wars” to Luke Skywalker. Perhaps it was Alec Guinness’ delivery that made it seem so dark and almost frightening to me, like when Gandalf talks to Frodo about the Ringwraiths and the Shadow of the past. I literally pictured Jedi warring with their own doppelgängers.

To me, one of the most powerful moments in Star Wars is when Luke confronts himself in Yoda’s cave: Luke’s face revealed after he beheads Darth Vader. In the same way that Tolkien was disappointed that Birnam Wood did not literally march on high Dunsinane hill in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (and thus motivated Tolkien to create the Ents), I wanted something more out of the clones concept. But Dave dismissed my argument and said that such an approach was too dark. Anakin is supposed to be the human in the machine, after all. Yet still I wonder…

Stylistically, Star Wars seems perhaps even darker to me nowadays. The first three films Lucasfilm released were all dark and fairly gloomy. That maybe reflects the times we live in, a time more numb to violence and when our own republic is in dire jeopardy. In that, Lucas forewarned us with his fable of the fall of the republic and the rise of a dark emperor.

Watching the behind-the-scenes documentaries on the two seasons of The Mandalorian reveals a recommitment to hope, but also to the stoic. Ahsoka, one of Dave’s co-creations with Lucas, is introduced in live-action form, having anchored The Clone Wars with Anakin and Obiwan. The chapter where she appears is titled “The Jedi,” and it is a moody take on the telekinetic monk warrior.

Like Yoda or Obiwan Kenobi before her, Ahsoka has a Japanese sounding name. Being half-Japanese, I’ve always found this Asian tilt in Star Wars culture highly effective. It gives the universe a certain credibility, perhaps because of the stoicism of the samurai, Zen and the Far East’s adherence to certain aesthetic customs, many of them ascetic.

Filoni cites Kurosawa as a major influence for “The Jedi” chapter. He talks about the moodiness of Kurosawa’s film compositions, defined often by the contrast between slower character movements and greater energy in the background, such as wind in the trees, or in the case of “The Jedi,” which he wrote and directed, the use of agitated waters in the temple grounds to reflect Ahsoka’s two white lightsabers. Some might cite Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai or The Hidden Fortress as the main references for “The Jedi,” or Yojimbo, but with its enclosed city walls and court intrigue, it relates more strongly to Throne of Blood and Sanjuro for me.

Throne of Blood is Kurosawa’s take on Macbeth, and uses the restless fog in the Spider’s Web Forest to marvelous effect, contrasting it with the dark fate of Washizu, the film’s Macbeth. Sanjuro is the labyrinthine followup to Yojimbo and one of the great sequels in film history. Different from the fog in Throne of Blood or the water in “The Jedi,” it builds anticipation to a razor’s edge through an intricate drama of cloak and dagger. The nameless rōnin, now named Sanjuro, refuses to fight his nemesis, Hanbei, in the final showdown. But Hanbei insists. In one lightning fast move, Sanjuro kills him, his torso erupting in a geyser of blood, resplendent in black and white. “The Jedi” does not end with Kurosawa’s brutal violence, but its subtleties reminded me of Filoni’s sensitivity to dramatic space and flashes of visual panache.

I still remember clearly coming to Dave’s apartment once and being surprised by a papier-mâché Gollum lurking in the tree out front. He had made the little Slinker and Stinker himself, painting him with great care. But the most important thing I got from Dave, besides his gestures of fellowship, was the lesson that all great artists must go their own way.

Even if they are following in others’ footsteps, at some point they must diverge from those who went before, and step out of their shadows. Tolkien’s light and shadow. The Light Side and Dark Side. Transformative myths need both, but it takes the right touch, at the right time, in the right form, to make hope and history rhyme, to renew the promise of the past, present and future.

One of the best things in Dave’s gift from long ago — the THX-1138 DVD — was its excellent bonus documentary on the history of American Zoetrope, the heady independent film studio that Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola co-founded. Anyone who loves film and outsider art should watch it. Now mythic figures from film were a part of the first roster at Zoetrope. John Milius, who penned the script to Apocalypse Now. Carrol Ballard, who directed Black Stallion. And yet its initial incarnation pretty much failed when it produced THX-1138, Lucas’ first film and the studio’s initial foray. But from its ashes emerged many of Coppola’s greatest films, as well as Lucas’ American Graffiti, which opened the door to Star Wars. The rest of course is history.

As a writer and designer, who has contemplated Tolkien, fantasy, science fiction and myth for most of my life, I have often wondered what makes a creative work truly original. We all play in the sandbox of our influences, but there is a difference between extending versus transforming.

The “fundamental things” Tolkien noted at the core of myth — the engines of myth — don’t really change from century to century. But the medium and the melody does, and it’s the artists that reimagine the interface of truth that create new mythologies for their time, and for all time.

Yet without the extenders, there can be no bridge to the past or the future. Christopher Tolkien was his father’s keeper and his greatest landscaper. He continued to work in his father’s “garden” long after the elder Tolkien was gone, smoothing out the rough edges where he could, and enriching its soil for those who saw in Tolkien’s work a “far green country” that they wanted to know and understand. The Silmarillion would have never seen the light of day without him. There would have been no Unfinished Tales or History. All of these works will give critical context to Amazon’s upcoming Lord of the Rings series, reportedly the most expensive TV production in history. And while The Silmarillion is now seen as a monumental achievement, Christopher Tolkien’s recent edit of The Children of Húrin is particularly individual. Its narrative is perhaps the most bewitching and haunting meta-myth on dragons ever conceived. With its many twists and turns and horrifying tragedy, the tale itself IS the dragon.

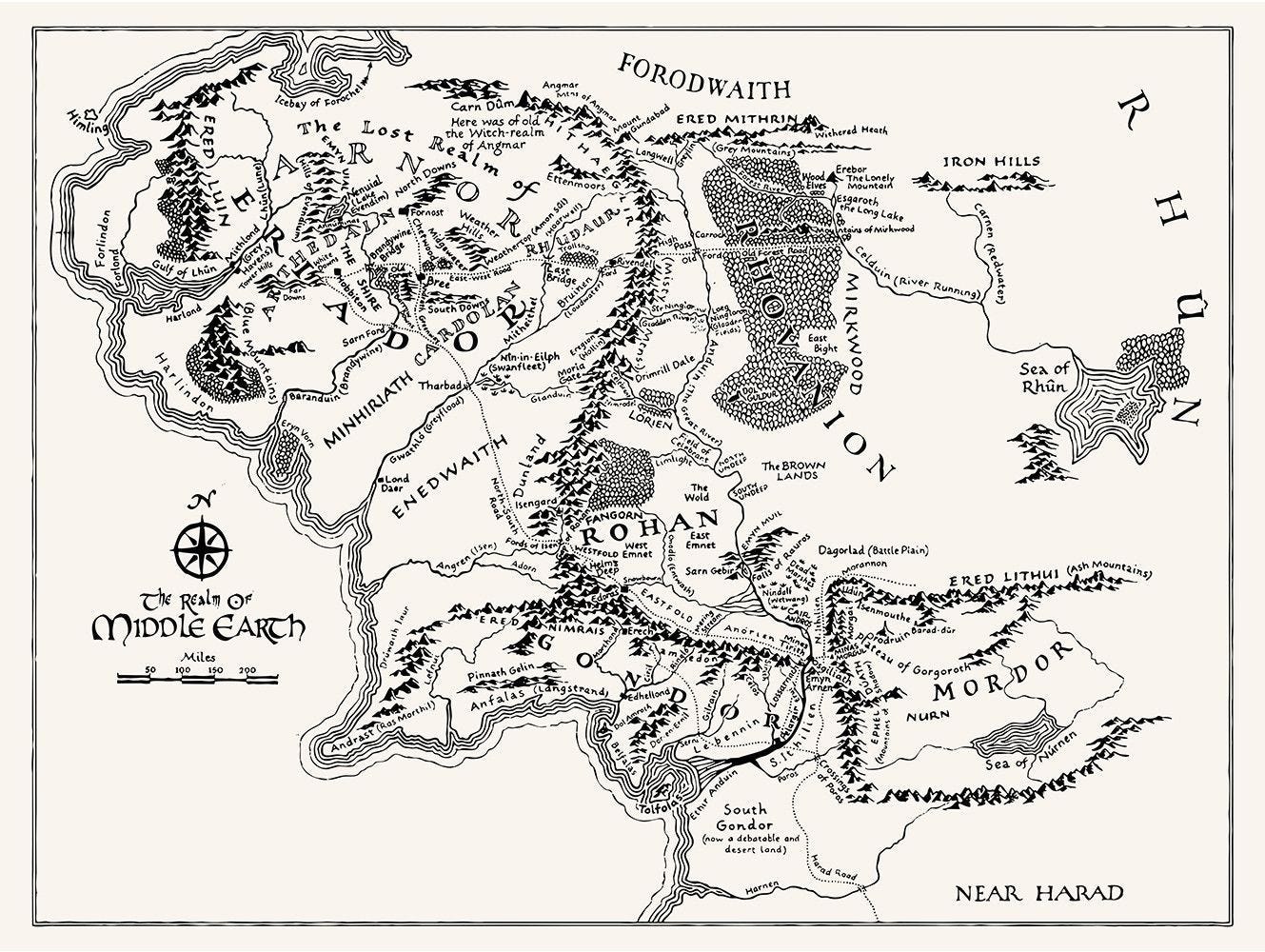

Not to be forgotten, the younger Tolkien also drew the most iconic maps of Middle-earth. Those are burned into the psyches of all Tolkien readers and fans, and in many ways set the stage for how all subsequent myth-worlds, from the RPG Dungeons & Dragons to MMORPG World of Warcraft, should approach landscaping any would-be fantasy.

Of course, one cannot forget the Peter Jackson films. The Hobbit trilogy was mixed. The “trilogy” part is the problem. Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, however, was a mythic breakthrough of epic proportions. It won universal acclaim and received the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences’ highest awards. I find much of it flawed, but when it gets things right, its unstoppable.

Christopher Tolkien detested the films. He felt they were a bastardization of his father’s lifework. They are, as the film critic Andrew O’Hehir once noted, about 10% too cheesy. Christopher would probably wage a much higher percentage, if he even ever watched them. It’s not clear to me that he did. I am of both minds. On the one hand, part of me is against extension. But on the other, it cannot simply stay a family affair. All myths are expansive social constructs that can live or die depending on the intent and character of its landscapers. At some point, it takes new authors.

The word “authority” comes from “author.” Authority can be oppressive or it can be gracious and enlightening. Tolkien, despite Christopher’s misgivings, argued for what he called “applicability” in myth and fantasy, not “allegory,” which he saw as tyranny of the author. That is, he believed in creating a mythic field wide enough and alien enough that it could inspire and belong to anybody at any time.

Certainly, there is something to be said for Christopher Tolkien’s defense of reading and the original text, and therein perhaps lies the enduring and stubborn appeal of J.R.R. Tolkien’s stories, and why his mythology still feels more real, or Hyper-Real, than all the others. And yet will people still read The Lord of the Rings generations from now, whether we’re living in virtual realities or whether our attention spans are obliterated by addictions to mobile computing and flashing screens? Will Amazon’s TV mega-series eclipse it or dead end?

Of course, no one knows. But we must evolve. That’s why every era requires new myths. My own experience tells me new transformative mythologies require us to dream them up and to shape them from “scratch.” You have to dive deep into the Cauldron and roam the Land. It starts with gratitude and a leap of faith. And if you’re lucky, a lantern and a map.