Is the Silmarillion on Screen Inevitable?

With media and tech companies launching "universes," none is vaster

One universe to rule them all. That is the contradiction in the air in 2021 that we’re considering as the production armies of the world’s greatest entertainment and tech companies escalate their war for the world’s finite attention. Variety puts it in these Manichaean do-or-die terms in its April cover story by Joe Otterson, “From ‘Star Wars’ to ‘Avatar: The Last Airbender’: How Big IP Is Driving the Streaming Wars.” The gist is that without well-known mythologies, today’s streaming platforms would lack the mindshare to best their competitors or leapfrog frontrunners. So everyone needs their “Mandalorian.”

One of the more interesting aspects of the story, however, is less about the obvious hunger for more “hits,” but the difference between “parallel universes” and “inter-connected universes.” The allure of the latter is for a deeper and ever expanding franchise in multiple directions. It’s not just about the product synergy of toys, comic books, theme parks and so on, but the ability to attach new spin-offs to mythic touchstones. And instead of those spin-offs acting as just cash-ins and derivative mutations, Hollywood is busy at work in transforming this very transparent franchise business strategy into “world-building.”

Another buzz word these days is “Metaverse,” which is often used more in the context of the Internet exploding into a “huge ever growing pulsating brain that rules from the center of the Ultraworld” — to borrow a phrase from 1990s techno ambient pioneers and psychedelic dreamers, The Orb, who with much of their fellow rave and electronic brethren, both predicted and helped imagine today’s digital universe into being. Of course, converging with the Metaverse is also the Multiverse, if you want to get quantum about it. It’s no mistake that the digital revolution has supercharged nerdy daydreams into today’s blockbuster lucre.

Two realizations stand out that hit me the past few years that moved what I already perceived intellectually to the experiential. Putting aside my own work in themed entertainment, it struck me as both funny and horrifying that Halloween in 2019 turned my Los Angeles neighborhood into a bizarre Marshmello fest. Let me be clear, I dislike Marshmello, the American EDM DJ that has taken Daft Punk’s faceless gimmickry to its logical and depressing conclusion — selling confectionary as music. So when I noticed every other kid, mostly boys I guess, traipsing up and down driveways and sidewalks trick-or-treating with white bucket-heads — marshmallow helmets that is — I laughed and cried inside.

Of course, in at least one respect, I was the one with a bucket over his head. I wasn’t on Fortnite — the battle royale drop-in 3D multiplayer game that has made Epic Games and China’s Tencent billions, as well as turn Ninja into the Pied Piper for the video game generation(s). Therefore I was “nowhere” and a “nobody” in the cyber sense. Whether we’re talking Russia hacking the 2016 U.S. election, Zoom booming, or games like Animal Crossing becoming the digital lingua franca for COVID kids, there is no denying that digital life is real life now. So, when I learned that Marshmello held a virtual concert in Fortnite in early 2019, my neighborhood marshmallow “takeover” months later made perfect sense.

Too much sense, maybe. Because the other realization that puzzled me also relates to another neighborhood of the streaming universe — Netflix. While I admired its early move into the “white space” of the online TV wasteland (anyone remember webisodes? I cringe) and its innovative choose-your-own adventure Black Mirror episode, “Bandersnatch” — based on a word and creature that Lewis Carroll invented and first used in 1871’s Through the Looking-Glass — for me, Netflix started to flail with its interface. At the time it was advanced and more effective than anyone else’s organization of content on a screen, simply because Amazon Prime seemed to not care about their UI and also because no one else was yet giving Netflix a real run for their money.

While I talked to many friends and fellow product designers about the Netflix data-surveillance model of showing me things related to things I watched — a sometimes effective but often less than satisfying outcome for myself, as I am easily bored by most TV and more interested in serendipity lest my brain become a Hungry-Man TV dinner tray — I had a nagging feeling that it was turning into a giant globule of confusion. The problem was that Netflix was all-in on this data approach (except for when they started their Spotlight featuring) and I didn’t use it enough for it to have very accurate data on me in the first place. Secondly, like I said, just because I liked one series because of its content, I was just as ready to slough it off, if it was a poorer rendition of the same topic or subject area. Finally, it felt to me that they weren’t just throwing spaghetti at the wall, but that they were throwing spaghetti at me.

There were other things Netflix was doing, like repeating the same content over and over in different categories but with different tile images, both to inflate the impression of their TV emporium but also to get data on which images I spotted better or would click on, because it had more colors my eyes enjoyed, or pop. To me, in the end, this felt like a brand that was still finding its central core, or perhaps didn’t need or believe in one — yet.

Which brings us to why this “universe” thing is so important to the future of world mythology. The fact is, Netflix changed the game, but they also had it easier. They saw an industry stuck in its ways, and with the Internet shifting the currents and in fact transforming the whole information sphere into an ocean, they recut their sails and set their course for the pulsating “center of the Ultraworld.”

World-builders, meet Ultraworld-building! Which brings us to J.R.R. Tolkien and The Silmarillion, for I know of few other and in some ways no other fictional world that approximates an Ultraworld more than Middle-earth. Especially if we take The Silmarillion, Tolkien’s first mythological project, the foundational codex to history reimagined…

No matter how many legions of creatives and production monkeys a company marshals to its flags or its decks, none of it matters if there isn’t an idea worth marching and dying for. Not data, but an idea. Data is essential in our cyber world. Like living in a moonlit landscape, it reveals things and gives us the ability to see what’s happening out there. But the moon plays tricks in its phases and orbits.

Data is not the idea. Data is not even an idea. It is numbers and patterns. An idea has something else to it, something more akin to spirit. We might call it an image, and hence imagination, but that’s not it either, because what makes an idea good or magical — let’s leave bad ideas out of this for now — is the deeper ghost that moves underneath it, so that what we see and comprehend is both something instinctively familiar — an emotion often related to ancient or childhood experiences — and refreshingly new. So that it makes us think anew.

Ultimately, this is what Tolkien mastered, the art of creating ideas that in our DNA as humans born into a world of life and death can recognize what we are, reflections that shine both ways: into the darkest places and out to the brightest horizons. In other words, people can relate. So as Otterson notes, Amazon paid $250 million just for the rights to tap into Tolkien’s best known “book of spells,” The Lord of the Rings. When it was announced that the Tolkien Estate had granted Amazon the winning prize however, most fans assumed they also won The Silmarillion in their bid to relate. Surely Amazon went for the jackpot?

But they did not.* Perhaps it was the wish of Christopher Tolkien, the protector of his father’s legacy, who had also edited The Silmarillion into a publishable form in 1977 after the beloved author passed away in 1973. A half century later, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos helped clinch the deal in 2017, as he pursued a “Game of Thrones” for his streaming platform. The author of the book series A Song of Ice and Fire that HBO based its Game of Thrones show on, George R.R. Martin, is a devoted Tolkien fan, and one could say disciple (notice the “R.R.”?). Of course, sadly, Christopher Tolkien is now gone. He passed away at the beginning of 2020.

So time marches on and a new age dawns. The cover art to Variety’s issue on the reign of “Big IP” is a nifty image of constellations in space wheeling around little blue planet Earth, as if we’re embarking into a Multiverse of dreams. Just like the ancients, we still love seeing things that aren’t there. Constellations are both just coordinates and the ideas that they draw. Those images were projections of our earthly experiences onto the sky: gods, bulls, bears, warriors, and so on. Tolkien loved the stars. They are riddled throughout his mythology, espied through the tangled boughs of trees, awakening the Elves by a lake, shining above the Shire, glimmering above Sam through the dark smokes and clouds of Mordor.

In fact, Tolkien’s whole mythology sparked from one name that was an angel that was a star sent to “middle-earth.” That mysterious name, “Eärendel,” lit the whole bonfire of his imagination, provoking him to ask endless questions about things that were, things that are, and some things that have not yet come to pass. It’s a humble and magical place to be, looking up at the universe. As his most famous hero Bilbo Baggins sings about roads and hills at the end of his long journey in The Hobbit, or There and Back Again:

Roads go ever ever on

Under cloud and under star,

Yet feet that wandering have gone

Turn at last to home afar.

Eyes that fire and sword have seen

And horror in the halls of stone

Look at last on meadows green

And trees and hills they long have known.

So if we’re talking worlds, universes and metaverses, parallel, interconnected or otherwise, then perhaps we should brush up on our mythological astronomy. Not the astrology of the ancient Greeks and Romans, or even the celestial bodies that guide navigators and farmers, but that inner sense and inner map of the moral universe and our imagination therein. Always at the heart of Tolkien’s creation roams and rests the adventurer, the explorer, the wandering wizard and the missionary Elves heading into Uttermost West. By immersing, we grow.

It’s also important to know an IP’s history. For Amazon’s much-anticipated Lord of the Rings TV series, reported to be the most expensive TV production of all time, began with Warner Bros. and the Tolkien Estate, following the settlement of a lawsuit between the two parties, who shopped around a TV license to Netflix, Amazon and HBO. Amazon wanted more control over the show, so Warner Bros. exited the deal, though their New Line Cinema (owned by Warner Bros.) would be involved, along with the Tolkien Estate and Trust, and HarperCollins (the U.K. publisher of Tolkien’s works, owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, which reportedly bought Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the American publisher of Tolkien’s works, last month). That’s some serious commitment.

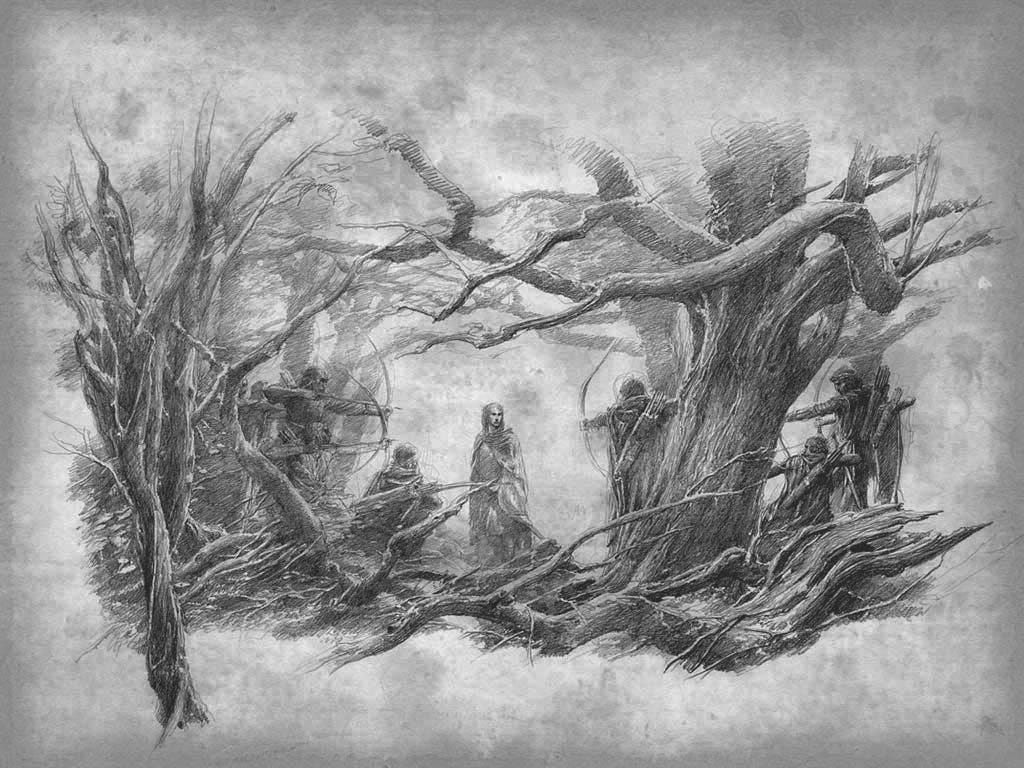

Oh yes, the plot thickens, because apparently News Corp also perceives Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s publishing rights to Tolkien’s books as that subsidiary’s golden goose. Now, the fact is, most Tolkien fans haven’t even read The Silmarillion, nor especially The History of Middle-Earth or other ancillary works like his Unfinished Tales. But this is where things like data do matter. Because for the last several years HarperCollins and HMH have been putting out well-received Tolkien posthumous works edited by his son, who worked furiously to the very end: Tolkien’s Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien and The Fall of Gondolin, all beautifully illustrated by Alan Lee, have delighted fans. Theses three tales comprise the main pillars of The Silmarillion.

It hasn’t ended there even. Just this past October, Tolkien’s publishers reissued Unfinished Tales, first printed in 1980. This time they commissioned artwork for the book from three of the world’s premier Tolkien artists: Alan Lee again, John Howe (both he and Lee were the concept artists for Peter Jackson’s Tolkien films), and Ted Nasmith. As I have started to re-engage with the Tolkien fan community, I have also noticed how many Tolkien fans on Twitter are clearly devoted to The Silmarillion, choosing handles inspired by its characters and pledging their allegiance to its deep and rich mythology. News Corp must have data.

So perhaps they are making a very big bet. For the film and TV rights to The Silmarillion, THOME** and Unfinished Tales, have never been sold. Could it be, that if Amazon’s series succeeds, that the Tolkien Estate and Trust, with Christopher now gone, may grant rights to the highest bidder or right steward? Might they give that power to Amazon, with News Corp sharing in the windfall?

“No one ever influenced Tolkien — you might as well try to influence a bandersnatch.” These were the words of his friend, the famous author and philosopher C.S. Lewis. I think it is a very important observation, not just about Tolkien, but about the nature of genius and creativity, especially when it comes to “world-building” and “interconnected universes.”

This is not a post about the unique power of The Silmarillion — suffice to say we have explored and continue to explore its long deep river of spiritual and artistic grandeur — for its genius is part of the fabric of all of Tolkien’s Middle-earth. It’s as important and pervasive as the stars at night, a metaphor that Tolkien obsessed over for 60 years or more, and in many ways represents the vast sky of dreaming that he weaved — constellations of wonder and wisdom. Not only the quality but quantity of invention in Tolkien’s works outside the better known, is profound. There is a galaxy of characters and places that evolve over eons. As the deep background to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, it is also the forward momentum to Tolkien’s universe from the long past to the far future.

There are other deep wells. Frank Herbert’s Dune comes to mind, and is in the HBO Max and Warner Bros. hopper. Apple TV+ is mining Isaac Azimov’s science fiction classic, The Foundation — mind-blowing in its concepts. There is Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Nickelodeon) and even lesser known masterworks, but still ripe for the “Big IP” treatment, such as the epic Usagi Yojimbo, the similarly epic but bloodier Lone Wolf and Cub, the recently lawsuit-settled property of Robotech, or even smaller but pulpy works like Conan the Barbarian and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser — both story indicators of where Netflix’s deal with Hasbro could go in terms of Magic: The Gathering, or with Paramount Plus perhaps pushing into Dungeons & Dragons territory with Paramount’s 2023 film. Netflix is also quadrupling down on The Witcher, which owes an idea or two to Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné saga.

In many ways, there is no bottom to this mythic sea. Yet not all of them, or even most of them, are of enough quality, to sustain planets and galaxies. Even if our future of Ready Player One and Two exhausts the creative depths of human history, turning the future into a NASCAR supermarket spaghetti fight complete with leaderboards and a Marshmello oldie-but-goldie shoot ‘em-up Fortnite concert broadcasting to the space federation at half-time, hot dogs in hand with augmented reality emoji in our relish smiling at us, there’s still Tolkien.

Yes, still, his words will be there, even if it all gets super-sized to sillier and sillier proportions, his ideas mutating across social media and the Multiverse. Because The Silmarillion is tailor-made for TV, the assumption is that the screen version would eventually overshadow the text. Yet in this case, that text could use more exposure in my opinion. There are so many potential paths it can be taken, from the coming of the Valar to the exodus of the Elves, to the betrayals, murders and wars that rack and ruin for hundreds and hundreds of years.

And it’s not all Game of Thrones style. There are beauties and wonders and an imagistic bittersweet poetry so utterly strange and transportive, that generation after generation of artists would delight in its telling. It could blow people away. Of course, before then, Hollywood might face a “spiritual backlash,” as Julie Plec tells Variety; the showrunner of CW’s Vampire Diaries, she reckons that eventually most TV audiences will thirst for more original content. But that still just brings us right back to Tolkien, as we put down our hot dogs. So far, there’s never been a half-time show in nerd-vana’s Tolkien-verse. The Silmarillion and its ancillary works are the definition of original and fans will keep going back.

His Middle-earth could be hopelessly lost to byzantine film and TV rights — circa 2021, how will Peter Jackson’s films be reconciled with Amazon’s creative fancies? — and without that ability to cross platforms, to bridge between worlds, it could be that Amazon’s plans could fall short, stuck with a parallel universe instead of an interconnected universe. But eventually, even if it’s decades or centuries from today, I believe the Tolkien Estate will grant the rights to all of Tolkien’s mythology. Will that be a good thing? Strangely, I think so. I hope so.

Breathing life into a universe takes time and care. There is the writing and the painting and the crafting and the filming. But what is it like to breathe in there? What is it like to act in there? What is it like spending year after year fantasizing in that world? Some of that magic can be made with bigger budgets and computer graphics. The higher fidelity the visuals, the more convincing. Even so, you cannot force inspiration or revelation. That last part takes not just great storytellers, but luck, and timing. This means letting ideas grow and pulse from some highly personal core. It takes a bandersnatch of sorts, someone with a strong sense of where we need to go.

Like Lewis said, Tolkien was original. He certainly took inspiration from other places and people, and from history and existing mythologies. Despite Lewis’ statement about Tolkien being resistant to influence, he was also being a tad sarcastic. In fact, Tolkien benefitted greatly from the feedback he got from his friends and family, especially from his son Christopher and from he and Lewis’ Oxford literary group, The Inklings.

Still, he had something in his pocket. He was a magician. I believe, and the evidence greatly supports it, that at his core was something far more profound. What was it? When I think of this vast armada of franchises rolling out across TV screens, movie theaters, video games, mixed reality, theme parks and toys, I can’t help but come back to the basic fact that Tolkien’s books are wonderful to read. Maybe whole generations will skip them for the easy zap of Jackson’s spirited interpretations. But there’s just no substitute for the real thing. And when I contemplate that fact, I return to the realization that The Silmarillion is a dimensional thing — time — that is infinitely deep, every word a gleam.

And even if we’re colonizing Mars and migrating to new worlds, dodging asteroids and leaving our solar system, after another hundred, two hundred or three hundred or millennia of space travel, maybe going through a wormhole to a long time ago in a galaxy far far away, we will look back with longing on our home and the Earth we’ve left behind. And when we do, all time will loom foremost in our minds, memories — myths — dreams that flash us back to before we were born, eager to journey back as spirits that can remember with open eyes.

I don’t think that will ever change, because Tolkien went right back to the beginning, and walked right on through to you. Like the “Star Child” from 2001: A Space Odyssey, I can picture staring through our spaceship windows as we read or watch The Silmarillion on a flight-board entertainment system, looking down at the real Ultraworld, thinking how great it would be to go walk the Earth with an elf or a wizard, and with gratitude for the mystery at the heart of all living things.

Perhaps that could happen even earlier thanks to the parallel and interlocking Metaverse. But the more time passes, the stronger the cord that pulls us back to life’s greatest mysteries. Whether in screen space, outer space, or the white space on a page, who can create the best interface for reality? Just as Tolkien gazed upon the stars, the real trick is to turn at last back to the road, and go ever ever on.

*THOME is an acronym for the 12-volume The History of Middle-Earth, which contains all of Tolkien’s various manuscripts, backstories and unfinished works, in addition to other supplementary books like Unfinished Tales.

**Or did they? Based on research and talking to some of our sources, contrary to reports, it is actually not clear if The Silmarillion wasn’t part of the Amazon deal.

***Arthur C. Clarke once famously said that he knew of no other speculative fiction as powerful or as vast as The Lord of the Rings, and that is without consideration of The Silmarillion or THOME. He originally made the observation when he reviewed Frank Herbert’s Dune. The exact quote is, “I know nothing comparable to it except Lord of the Rings.”