Low Owl -:- Prophet at the Pond

Book One, Chapter Two

She woke. She was back where it began. Her hands were empty. She had tracked animal trails and a hawk’s tail that led to nothing, that then led to something else altogether: a mothling in the drumlin hills. Its wings seemed to disappear into dusk. Its antler antennae seemed to carve open a trap door in the sky. Its eyes within eyes sparked a cryptic fire, the lava of a group mind. Dwelling deep in timedrifts, she thought, the Ovyrrakrúsk was a lodestar and a crux.

Sitting up, she pictured the Moth and the Beetle’s name as she listened to the shadow clock turn: her ancestors created time chambers to remind them of the world before the Great Ice, with their thin intricate shafts of stone and glass that arrayed and caught light in interminable reminiscences of a warmer age. Blinded by blizzards of snow and sleet, moving over the north in relentless waves of the bitterest cold, they had survived off the frozen shores of the Lost Sea, and soon forgot. But her time chamber was not made of just stone but wood and sand. It was remote, far west in the highlands, across the sea, where the Exiles had escaped finally, hiding away in the glacier-cut Riverland of the Tam Tam.

Her family’s time chamber was called Ral Tanzul, the Gold Coma in the Sky. High in the Uplands above the deep gorges of the Magistrad, the river Tam Tam and its many streams and waterfalls gushed from the jagged mountains and the thawing glaciers, riving steeply down into a landscape of granite cliffs and grim drumlins, rich in metals and gemstones, moraines swooping down its northern outflow; Ral Tanzul was a redoubt above the Tam Tam’s tumult and removed from the ministrations and machinations of the Exiles below.

Once again, she observed its play of shadows on the walls. Shimmering in a soft blue at the center, she could see a small dot with a crescent shadow, moving ever so slightly across a great expanse. It was the waxing moon reflected from the sky through glass floating tiny before her eyes in a sea of rainbows. “Moonlight,” she said, observing the tiny moon, just now opening its first pale smile to the world, emerging again out of darkness. It made her wonder about phases and the invisible: was the rift-moth just a dream, or like the moon?

For out of shadow, Halkjavyk burned so bright in memory. The room was silent save for the gentle drips of melting icicles outside. The warm afternoon the day before loomed in her mind: the secret river and its narrow canyon in the Eskers. The long scar along the rift wall and its rough-hewn steps. The tapping of twice, then thrice. The red cloud of orange poppies on the drumlin. The lamb’s ears and cat lilies. And the mothling inside the flower cup. Over the moraines and the throb of the rivers rushing through the land, she felt the pull of his hand.

She reached by her head on her bed and there she found the cool petals of the cat lily that Halk sat in. Its center was a dark violet that engulfed its thicket of yellow and red stamens, stigmas and styles, splashes of indigo bleeding near the ends of its large white tips — peninsulas in a sea of pearl. He had told her to pluck it to remind her it was no dream. And so there it was, in her hands, springing his vorpal ghost back into her mind’s eye.

Carefully putting the lily into a pouch, she got up. She opened the door and walked outside. There were still patches of snow in the highland meadow. They were shrinking and vanishing. She walked to a trough by the side of the lodge and dipped her hands in, cupping ice cold water that she splashed on her face, wiping it clean of sleep. She grabbed her bow, her knife, her spear, her axe, her arrows, and strapped them tight. Hunting was an instinct, but now she thought twice.

Spring was here and yet the land seemed as quiet as the afterlife. No signs of deer, boars, rabbits, mountain lions or bears. Only birds and squirrels, frogs and toads, and bees, dragonflies, ants and beetles, and the Ovyrrakrúsk. She looked out and saw the cold winds blasting snow and ice off the tops of glaciers stabbing from mountains both near and far, as a cloud moved in front of the morning sun, casting its shadow. She listened quietly to the murmur of ice-melt streams.

“Aratarasu,” she repeated quietly. The sounds of his name flowed from her lips, she imagined, like bubbles rising from a fish in a pond. “Lord Beetle, he who is there and not there,” as Halk had said. She wondered, would his court come?

Right then, she heard the cry of a hawk high up, and then the answer of another. There, they flew under the grey belly of the passing veil. One from the East and one from the West. She wondered if one of them was the lucky hawk who had called her to Halk’s domain and that she followed through the serpent kame.

Even with her sharp eyes she could not make out any markings she recognized, and she could not quite tell their size compared to the tree tops or the sun, their distance too hard to fathom. But one of the cries had a familiar sound to her ear. It was a screech within a screech, and as the first echoed through the air, the second echo pierced higher and longer. It made her think about the tail of a comet across the sky, or the meteor that skipped across her mind. It circled around the other hawk, then it dove, and then opened its wings again like a wind-jolted kite, and circled lower in opposite flight. Round and round they came.

She noticed above their circling and above the grey cloud, the crescent moon cresting with the faintest silver, its true size much bigger than the tiny one she saw crawling on her chamber wall. That slightest of shifts in light and cloud and moon reflected earlier by the shadow clock struck her as strangely reassuring. It was a stark reminder of the slowness of time as well as the distance of kind. What was the moon after all? It too was a clock, a marker of rebirths, the hunter’s light, the lover’s guide. Seeing it was always a good omen to Greil.

It was a deeper rhythm: the moon. It was there to ponder. It made the night more than darkness. It made the day more than visible. Perhaps it woke the butterflies from their cocoons. Or maybe it gave the Grand Moth his truth. Her mind turned to questions about his origins: Did the Ovyrrakrúsk go through a metamorphosis millions of years ago? Did Halk come from an enclosed world, a caterpillar enveloped in darkness, starting as one form, then waking up into another?

The hawk cried again, an echo inside an echo inside an echo. The moon floated in a sea of blue amid the gathering storm clouds, tendrils of vapor creeping round it. She saw it now, from low to high, the humming and bumbling bees trailing amid the leaves nearby, the tops of tall trees towering toward the sky, the crying hawks swirling in courtship, the brooding clouds shadowing and hovering from afar, a flash of lightning, and the moon fading as the thunder jarred. Heaven and earth, one and the same, from the falling star to sun over the moraine, erasing time.

She walked to the stump as she pondered the moon and its play on yesterday. What else was so perfectly round? Bubbles came first to mind. Like the ones she imagined when she repeated the name, “Aratarasu.” Ripples from raindrops and pebbles. There were yolks, and the setting sun too. The pupils and irises of eyes. But then no other? Mushroom caps? Blueberries? Dandelions? Craters?

“A-ra-ta-ra-su,” the sounds rolled again off her lips like fish bubbles. The thunder grew louder, as if in response to Lord Beetle’s name, echoing off the glaciers and mountains and trees. Listening closer, she could hear the water rushing off the Uplands into the steep gorge of the Magistrad. At that moment she saw a large green praying mantis, an Ózil as her people called it, a “green monk.” It was crouched on a pile of firewood, waiting for the future.

Or was it? That was its natural state of being, cleaning its claws after a meal, she thought. His large green eyes scanned the horizon, his head turning at the sound of another lightning strike. The clouds drifted closer, the grass bent further, her lodge and its eaves grew shadowier.

Kroom! The sky cracked with a deafening boom. She started. A shard of light struck down off the ridge, lighting everything up in a ghostly white, then gone, everything even darker than before, the hair on the back of her neck standing up, and the Ózil as still as if he were dead.

Then the first rain drop fell, and the mantis still prayed, but cocked its head, listening to the drop bursting into smaller drops. Then the next rain drop came, falling in the dirt between her and the insect crane. Then another, and another, and another, far apart. Time passed and the Ózil did not move. Nor did Greil. It drizzled and then poured, the drops falling closer and closer together, for what felt like an hour, the thunder growing louder and louder.

Waiting, a little wave of mischief brushed her brow. She put her right hand on the stump’s bark and peeled off a long thin strip that slightly bended with an arc. She pulled her bow out with her left hand, raising the strip to its string, then pulled it taut. Her eyes on the green sentry, she breathed in, prayed for merry havoc and a true mark, then let go.

The bark flew through the air right at Mr. Ózil on an arc that brought it down right at his feet, landing with a thump. Startled, he jumped off. Behold! He had wings! She had never seen a praying mantis go from prayer to flight. That made sense. If it only walked, how would it get far, even in its green disguise? It looked like a giant grasshopper, she realized, but it did not have its speed as it glided into the meadow and the shade. How well could it fly? Maybe not so well, she thought, as it landed defenseless in the open field.

Right then, a sparrow swooped overhead. The mantid froze for a moment. Greil was standing now, watching it, tense. The sparrow turned course, circling above, scanning the earth. Then another flash of lightning, followed by a rolling thunder, shaking the damp air and the soil. Perhaps startled and distracted, the bird didn’t see Mr. Ózil. Instead, it banked and disappeared into a curtain of rain.

Relieved, Greil looked back down where the rain drops thumped and then seeped into the ground. It was a silly joke that almost turned her mantid monk into bird-lunch. She scanned the black dirt. The green prayer too, was gone.

Only here in Irèlia, she was told, did so much come so close. It seemed even more so high up in its wet cold Uplands above the Magistrad. Here, by Ral Tanzul or on her excursions into the ice-delved land, she watched how the turn of weather and the dueling of animals changed fates in the blink of an eye. The praying mantis had taken flight at her impetuous prompting, and a sparrow circled for the kill. The green prayer was doomed, if only for the strike of lightning.

She often thought, was it by luck or by design, or were the two one and the same, like heaven and earth? Twice, then thrice. As soon as she had that thought, a little shadow appeared on the sand where she stared, then grew on her hand. Halk was arriving with his lance held out like a fishing rod, as more lightning flickered near and far, illuminating his green, red and indigo wings. As he landed, his armor gently clinked, kneeling on her open palm.

“Hail, Greil!” he said, bowing down his black scalp with its green fin of hair and strake of antler-antennae. On his knees, his obsidian armor gleamed in the grey light. He outstretched his arms with his bee-striped lance before him in a gesture of peace and friendship. He then stood up and smiled. Happy that he hadn’t been just a dream, she raised her right arm. He quickly climbed up so they could confer face to face.

“The Sky Lord is grumpy,” he observed, looking round. “But no matter, my dear! For you have made the call, and Aratarasu will come. Not here, but there, past the forest to a lake, then a pond, where lily pads and water weeds adorn the calm.”

Looking where his spindly finger was pointing, she knew exactly where. It was a decent trek through the woods and over the western hill ridge and moraines that ran in between the valley and the high lakes and rivers beyond — Ralm Goorvalig, the Riverland of Irèlia. It was raining hard and the storm blocked out the morning sun so much it seemed more like night. She took a deep breath, and blew it back out in a puff of steam. It would be a wet cold walk.

“Well, Mr. Feleran,” she said finally, “To the pond we go. But is there a reason why we are meeting him there, and not here? Does he not like wooden houses, chopped and made of timber? It would be warmer, Butterfly Lord, and dryer!”

He looked at the time chamber and smiled. He saw the wood, but he was most taken with its massive grass roof with its long sloping flat top. It almost reminded him of a tomb, or a cake frosted with green tea dust. It had a long wall with four sides around the house with one door and two small round windows. But his sharp eyes could also see little glass circles and squares of different colors all along its façade. He remembered such chambers from long ago when the Ovyrrakrúsk lived and worked among the Masters of Or’Loz.

“That’s an interesting question,” he finally replied, thinking about the time chambers in a colder nearly forgotten time, bringing his right hand to his chin. “I never thought of him that way, as a house guest or wayward lodger. But it may be. I’ve always just happened upon him by ponds, and rocky glades, and the like. He is very fond of ponds, you should know. And, well, I can’t say I have spent much time in a wooden abode myself, and what an odd house this is, I must say! Nor I doubt has he. Yet here I am, so perhaps that could change. Do you want to wait and see if he comes this way?”

“No, no,” she said. “That would be rude, I think, now that you mention his wont. If it’s customary, we will brave the cold and rain. I don’t mind a little weather, or even a lot. It’s more the lightning, though. It’s all around us now, and when it’s wet, well, it could knock us underground.”

“The underworld or under the earth? No matter, I know them well. I presume you mean dead? But not all under the soil is dead. Quite the contrary, my lady. There are worms and ants and termites and beetles. There are roots and seeds and spores and eggs, and the tiny fungal cities that push up into toadstools and mushrooms.”

“Why yes, my mother and father have taught me much about the dirt and the rocks, and the rivers and the lodes that run underground, the wells and the steam from springs, that push up water and sometimes elixirs and poisons. I know about the grinding of vast sheets of stone and the fiery heat at the center of the Earth. I’ve seen trails of smoke as the land wakes up from the Ice and the Great Sleep.”

His eyes glimmered. He looked back at the time chamber behind her and then intently at her face: “I see it now! This house is indeed a time chamber, like the great mounds of old, that my people learned from Lord Beetle and his Kirrai, the Bug Masons of Vashvaroun, and that we taught the Magi of Korin long ago.” He squinted now as he studied her eyes: they were brown and hazel with flecks of yellow, green and amber. “You are not from around here, are you?”

“Why no, I am indeed from around here,” she said, with a flicker of anger stirring inside her, forgetting what Halk said about time chambers and bug masons. “I’m from around here, but I’m from around elsewhere also. My father’s people came here three hundred years ago in search of shelter. They are the Magi of Korin.”

“But they are not hunters!” he said, surprised. “And you do not look like them. I knew one other from around here that I helped many many moons ago. His name was Rukúschtra and he was an Irelkan of Irèlia. He too was given the calling of Aratarasu, but he knew nothing about the wise ways of Or’Loz. Do you?”

“Yes but only a little,” she said, her voice quieting to a whisper now. “My mother is Irelkan and our tribe has been in these highlands and valleys for thousands of years stretching beyond memory. We know the barks of every tree family, the color of every leaf, the path of its many rivers and streams, the tracks of its animals and the shape of its hills, as the ice reshapes and tills. Her name is DaSheen, a witch and shawoman of the rain-swept fells.”

His admiration for her grew as he listened to her speak about her ancestors and her knowledge about the land. He knew there was something different about her. That she was tied to the Exiles of Orlan Kan that made their way to the Magistrad centuries ago was not surprising. But that she was part Irelkan and Orlantian was far more intriguing. He had kept his distance from the Magi of Korin over the iced eon since the Great Tempest, but here, like the phases of the moon, was a glimpse into a lost world he had long abandoned.

“Who was this Rukúschtra?” she asked, noticing he had drifted away in thought. “I’ve never heard of him. I thought you had never met anyone like me before. Was he a hunter from the Magistrad below, or a lone woodsman?”

“I did not know him well, I’m afraid, for I only guided him a short while,” he said, with the slightest hint of melancholy. “I tried to lead him to Lord Beetle through the rain and the lightning, but he was too in love with the wild, and disappeared over the moraines. That was more than a thousand years ago, long before your father’s kin came to the lake lands.”

For the first time she sensed a deep lacuna in Halk’s soul. There was a vein of loneliness there in his long memory. Was he the last of his kind? She suddenly wondered. While she had heard about Grand Moths from her father, she had long thought mothlings were just illusions from tall tales of old. Crack! Right then, the lightning tore through, and his eyes within eyes flashed blue.

Time had entered a pool. The deep past was sloshing into the present, and the future now seemed to creak open as the sky poured down and the thunder rolled. Raindrops, big on his small frame, amoebic and drooping off, absorbed into each other on his obsidian plates of armor, a swirl of black and blue light that made her think of the night sky. Water dripped from his antennae and his wings. The storm clouds parted briefly just enough so she could see his curling smile.

“Well, Greil,” he said with a little chuckle, looking up at the darkened sky. “Aratarasu loves the rain, and he loves lightning especially, you should know. That follows him, it seems to me, wherever he goes.”

With that, she put her boots in the growing mud. It bubbled around their threaded rims. Heavy raindrops pelted her head, shoulders and gear. She unfurled a dark grey cloak from her pack, and pulled its hood over her head. Halk flitted up her shoulder and settled on her collar bone.

“I’ll tell you,” he laughed, “Kyrraskala, the drops are much bigger for this Butterfly Lord. At my size, they are like goose eggs splatting all around. They make quite a pounding sound and can jar the crown. Usually, I am under a log or a rock.”

Listening, Greil bent down, and picked up a big oak leaf with wide lobes and indented folds and handed it to Halk, who then held it over his head and arms like a slanted roof hanging before his purple blue wings. Seeing he was sheltered now, she stepped, breathing out more steam as she went. She left her spear behind so not to attract the lightning. Both hands on her bow, which she wrapped around her torso, and with her long axe in her belt, she made her way off the main path through the tall grass, into the trees as lightning shook the wide meadow.

They quickly came to the stream that ran along the northwestern corner of its woodland edge, the one she listened to most astutely whenever she daydreamed in the time chamber or prayed outside. In front of her were small stepping rocks, the water rushing round them, with sand and dark mud under its infinite gleaming. Raindrops made little ripples in its undulating effluence, wetting boulders and tree stumps as she hopped over this bend with that wend. Tumbled beams sat across its braided strands, forming a passage through many islets. Again the lightening flashed, and all about her countless blades of grass, and bushes entangling the river air, gently waved as the sun’s muted glow played off fluctuations of shadow, leaves whispering in dreamlike murmurings.

“So, how did you find me?” she asked, as the thunder trailed and she finished crossing the braided stream. “I wasn’t sure if you would come. I thought maybe you really were just a dream, and I had lost my mind in a winding stream.”

“I’m sorry, my dear!” he replied, shouting. “You’re going to need to speak up! I didn’t hear a word you said! The thunder got in the way!”

“Was it hard to find me!?” she asked, changing the question slightly and raising her voice. “I would have thought you had to follow me!”

“Well, in a way I did!” he said. “I followed your dreams. Do you remember what you dreamed? To me, it was fascinating! But to be entirely truthful, I followed you yesterday after you set out to return. I followed you down the riven rock and into the Riverland and across the cold meadows to the edge of the forest. But that’s where I stopped. I wanted to make sure you found your way back. Because I’m curious about you too. I didn’t want you vanishing on me like a dream.”

“Well, I don’t remember my dream,” she said. “I slept very well though, Mr. Feleran. And you don’t ever have to worry about me finding my way back. I’m a hunter, so I know how to track, and mark my way, and read the signs, even when they look different coming the other way. Although I have to say, I have gotten lost from time to time.”

“Hmmm, it’s good to get lost, is it not?” he asked, a wry spark in his voice. “It’s funny. Because I can fly, it is very hard to get lost. I don’t recall getting lost in a hundred years or more. Maybe never, now that I give it more thought. Isn’t that sad? I miss when the world was bright, and new! Like a great sunrise that lasted a hundred thousand years. That’s the story of the Ovyrrakrúsk. We’ve seen so much. What more is there to see? But that’s why you intrigue me, and why dreams are so important to me. Thank the gods for Lord Aratarasu.”

Right then they came upon a dip in the forest, that led down into a dell. It was dark and dank in front of them, as the rain dripped from far up and trickled down on them, running in rivulets from branches and leaves. Greil pulled out her axe in case she needed to clear away some bramble. They entered, stepping on this root and that log, over that bush and that moss, by mushroom patches and lichen bunches, onto this slab and under that boulder.

For a long time they made their way in silence through the dip. They came to a grove of redwoods where a fairy ring of pine mushrooms grew round its shadowy edges. She kneeled down and picked several, putting them in a netted pouch so their spores could keep sifting out. As they walked on, they happened upon lion’s mane mushrooms too, reminding her of the icicles on her lodge that Feleran had watched disintegrate in the rain.

Her people called mushrooms the “children of the forest.” They kept them fed in a pinch. But some could also poison and even kill. While others could open doors in the mind, or even shut them close with shadows that plagued dreams the rest of their lives. DaSheen had taught her which ones were good and which ones were bad, and which ones were decoys. But there was one that remained a mystery called the Black Atom. It made not just one mad who ate it, but a civilization through unseen cracks. And yet, some said, it could resurrect.

“So what did I dream?” she asked. “If you are the Dream Keepers, can you also interlope and see what I see? That’s not the most comfortable thought, my lord. But I guess with you, it’s not wrong, because I asked you to take me on. There are of course many tricksters about. Perhaps that’s why you were made so fine and encouraging, and as small as a mouse?”

“I’m not allowed to say,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons why we’re called the Dream Keepers. If I told you, I would not be keeping dreams. I’m keeping it safe for you while it steeps and transforms your being. Ha! Perhaps like a mouse, this Moth stores them away for life’s winter. While you cannot remember every dream, it does not mean you did not have them. What we do is deepen them for you. And if you learn to sleep as you walk, and walk as you dream, over time, you will be able to recall the brightest ones in complete clarity. Unspool them, and thread them, and even find the far reaches to where they lead.”

“Do you always speak in riddles?” she asked with a chuckle, as she picked some phantom mushrooms and blue elf caps. “I suppose I cannot pry all of your secrets. Yet it seems strange that you can see my dreams. How is it that your people came upon such an unusual talent? Did someone give you a spell? Or a key?”

“Your dreams!?” he said with a smile. “Perhaps they are our dreams, all like water taken from a deep deep well. No, my lady, it is not a spell. No one gave it to us. It’s more a curse, than a spell. We didn’t ask to guard the spirits or every thought and their trails. Since we fell from the sky to Meteorhome, we have always seen things very differently. We have double vision, and double hearing, you might say, even double lives! It’s not just that we can see dreams, it’s that we know what makes them, who visits them, when they come, and where they go. But none of that matters as much as why, which eludes even me. For words fail.”

As they talked, they had made their way back out of the dell and soon came upon a ravine with a little trickling stream. The Goorvalig was a good hike through the forest still, where many ponds speckled the shores of glacial lakes in its interior reaches. This was the halfway point. Words failed, he had said. So she wondered, grasping for some way to picture what he described. His riddles, they had a rhythm and a beguiling form to them.

She stopped to let the elusive drift off. Closing her eyes, she listened to the rain drops pelting the leaves, branches and earth. She felt the cold air enter her chest as her lungs breathed in, like mist falling into a deep cave. She meditated on his words about the well and the emptiness of her forgotten dream. Slowly, an image emerged in her mind. All she could imagine was a box with a keyhole, but no key. Inside it, she perceived Lord Beetle, waiting for her, patiently.

She turned her head and looked much closer at Halk. For the first time she perceived intricate striations and lines under the reflective obsidian glass of his mask that ran along his nose and around his green and blue eyes — the gleaming windows of eyes within eyes — that ran down its plated visor beyond his chin. He looked in the rainy light like a knight. He was crouching deathly still, holding up the big leaf above his head with his lance, the rain dripping off onto her shoulder. Behind were his green indigo wings, dark toward the center, and growing brighter at the edges like moonlight on sand, with flecks of yellow and red on dark islands that evoked campfires and drum circles in a deep blue sea.

“I see,” she said quietly. “Secrets that can’t be shared. Riddles that lead to nowhere. It’s like a recurring dream. Or mysteries that lose their magic in the light? I was sent up here by the wizard and the witch to spend the winter in the Uplands to hunt and pray until the first spring moon. I have woken each morning to a clock made of prisms and shadows and invisible wheels. I have caught almost nothing and have met no one. Until yesterday, when I met you after seeing a star blaze across the sky skipping like a stone on a lake. Today I saw the first sliver of a moon and called Lord Beetle’s name. And now I see a box that is locked.”

“Kyrraskala!” he said. “I know that box. The Dram, it’s called, where the Deep dwell. It’s a box and a drum, my Greil. We call it Kyvaliya in our tongue, which means the ‘lost door to wonder.’ It is a vision of the sacred that only comes to the very few who Aratarasu summons. And ‘who is summoning who?’ you might ask. I have wondered that too.”

He carved the air into a diamond with his flat hands, then moved them down, creating the shape of a cube, but looking on from an angle at one of its corners as he turned it, so that she realized the Dram had many sides, both inside and out. In the same motion, he then cut a circle, making space between edges and curves. As he drew his hands away, the idea of the diamond drum that became a box when it was turned this way or that way, remained etched in her mind, a vessel that could hold anything or anyone.

“It protects and unfurls your deepest held dreams,” he said. “Such dreams came to this world from long before we were ever born. So say the Wise. We call those the Drames. There are keys to each dream, and each dream is a key to even deeper mysteries. The keys are sacred words, which can be sung. They are fiercely guarded, with a maze to each one.”

“You spoke of a ‘Meteorhome.’ Is that where Ka-vahl-ee-ya?” — he nodded at her slow utterance of the box-drum — “where Kyvaliya, the keys and the box-drum, come from?” she asked, waiting for another wrinkle in his words; for every time he spoke, a new riddle emerged, riddles within riddles within riddles, ripples upon ripples upon ripples, of the mind.

“Amralas?” he said. “That’s our name for Meteorhome. No. Lord Beetle grants the keys. We only guard them.” The sky crackled as lightning came down just on the other side of the ravine, its thunder shaking the earth. “No coincidences,” Halk shouted. “Not one!”

The rain came down harder. In front of them up just a little way was a giant alder tree that had fallen across the ravine. It had been there long before Greil came on her many scouts. It was old with moss and lichen draping off, all of its branches and roots shorn or worn away so that it was now an aging beam.

“Shall we cross the bridge?” she asked, as the rain hit them and dripped off. She knew that somewhere on the other side was the dram, drame, dream.

“Why yes,” he said. “Lead on!”

The storm clouds heavily cloaked the forest. The sun was still only a rumor in the wet woodland darkness, occasionally breaking through here and there. She had many questions as they walked. About Aratarasu. About Amralas. About Halk.

But she did not ask. Each time she asked her new friend, she only ended up with more questions, more forks in the road, more winding paths. Getting lost is good, he had said. So it seemed to a mothling, she thought, but maybe not to a huntress. And yet, she believed there was truth locked up over there. Each step she made in the wet soil, on wet leaves, over rocks and moss, she was finding new things, new views, and that was hunting too. There was no way to know without first not knowing. And so, the mothling had his own questions too.

“I saw you trick that green mantid,” he said. “Insects are not playthings, my dear! Though I know you did not mean any harm. There are the spiders that trap, sting and make one ill, or even kill. Scorpions that scurry in the desert and strike. There are the worms and ticks that bore into the flesh. There are the locusts that eat the wheat. The wasps that torment the air. And the ants that build and build.”

“It is true, but I did not mean to hurt him,” she said, blushing a little in embarrassment. “I was just testing my marksmanship. It has been a few days since I practiced my archery. But it is also true, that I was growing impatient, and for a moment the idea came to me to mess with the Ózil.”

“Mess we all do, in this messy world,” he said. “While I may speak in riddles, I do not see you as my Ózil, if only that I can see the strength of your meditations. My riddles are not necessarily riddles meant to keep you out. They are meant to lead you in. For they are the only way I can describe that which defies the mind.”

“And what of that can be known?” she asked. “If one can even know it. I don’t want to freeze like a green monk in prayer, forever searching for something that was not there. You Aikyrrie, as the Haarynns call you, must also know that what they have long prized is what has long troubled even the wise. The cat people pursue those who waver on the road to enlightenment, who give into lies, who lose sight. They guard the narrows and the clears from the twisted and the accursed.”

“The Haarynns have no business here,” said the rift-moth. “For Lord Aratarasu has already chosen you. He has been guiding you since we left the lodge. Dreams are not just confined to sleep, Greil. Every waking moment, they shape us. Even now, this is dawning inside of you. I can hear it in your questions. I can see it in the shape of your breath. You are not cursed. At any moment, you can turn back.”

“It’s coming back to me! His name was Tammerak,” she said, Halk’s words sharpening her thoughts into a new insight, as if a key had been turned and the lid opened to the hidden box. “He’s in my thoughts now. I saw him last spring, with a steel javelin and a shield the shape of an hourglass, and on it the emblem of a blue sickle moon,” her voice rising with excitement. “His helm was unlike any I have ever seen. It had a great black brim that came out like a flat mushroom cap, and a top that went up like a chimney, with two tall feathers straight up on both sides like antelope ears, or your antennae. He reminds me of you, Sir Moth!”

She waved her hands up in the air in curly-cues, as if she was tracing smoke, creating the shape of his antlers and Tammerak’s feathers. “A strap made of thick red and yellow beads came down the sides of his face, lying lazily on his neck, and his chest, his thin black mustache and beard sharpened like knitting needles,” she said. “His tunic was magenta and his robe a deep night blue. He wore a silver breastplate, and his gloves were dark leather with studded pearls. He was a fascination on a horse, and I saw him just that once, and then no more.”

“Where did he come from?” asked Halk. “What you describe to me sounds like he was a man from the East, from over the straits of Simbesh, even from as far as wide Sarkadon: lazily knitting deep night blue pearls on a horse…”

“Killadran, I was told,” she said, looking at him curiously, as he smiled and uttered her own words back to her in another riddle of words. “Yes, I guess he was a kind of poetry, from far in the East. But there was nothing lazy about him or his horse, Mr. Feleran. He came bearing tidings of war around the shores of Lake Kelverrik, one of the Gavran Wars that have sparked in the erasures of glaciers, his errand tense as a bowstring and arrow.”

“I know of Killadran,” said Halk. “I know it well. Not all good things or good tides. But a noble people, is what I have always known. My tidings have often only ever come from others’ dreams. This is no different. You asked of Amralas? Well, Killadran is just south and west of my ancient home.”

“Perhaps we met in another life!?” she said, realizing that her ancestors might have known and even parlayed with Halk and his brethren, for she knew Orlan Kan was north of Killadran. “I would love to go to Killadran one day, and on to your home — the moth land of meteorites.”

“One day, I hope indeed,” he said, nodding his head. “But if we met, for me, it was this life, and not another, for I have watched hundreds of thousands of lives pass by me like waves and currents on a river. No, if I had met you, I would have known. Like Amralas or Killadran to you, you are the unknown. Now, this Tammerak and his feathers…”

He wanted to ask more about Tammerak, and she wanted to ask about his homeland of falling stars, but right then they came upon the pond. First they heard lake crickets nearby and the throaty croaking of frogs; the sound of distant thunder retreating far off, out to upland lakes echoing with clear tones floating to them over the face of cold waters. The rain was also letting up, dripping gently now, making a pleasing thumping music on leaves and petals.

“Ah, here is one of his courts,” said Halk. “Here, my lady, is the Lord of Dreams, lost and found, recurring and fading, from the beginning to the end, borne on the sound of thunder. Aratarasu, we have come to pray with you.”

She stepped up to the pond’s edge and bowed. Now closer to the water on her knees, she could see beyond the low hanging branches of the willow trees to the lake, which was now bright white and steel grey under the stormy sky as far off lightning flickered behind distant mountains behind. And the world outside the pond grew quieter and quieter as the rain drizzled on, bigger drops making ripples that emanated in languid discs of delight.

But by the pond it still seemed like night, with an alien moonlight outlining its mysterious flowing shapes, hinting at long forgotten secrets. The pond was dark and clear. It looked like its deeps went down forever. She saw bubbles coming up from fish, and could see their curving movements vaguely among the underwater stems and plumes of algae. She saw an eel squiggle through too, and a turtle sink back into its underwater lair. There were lily pads and water weeds. She noticed tadpoles in one corner and blue tree frogs on a half-submerged log in another.

Sploosh! — above water there was a red salamander diving in at the far end, stroking as he caught a worm with his curling tongue. A squad of fireflies flew by, from one towering plant to another, flashing green with liquid glowing in their stomachs. Red-eyed dragonflies hovered over stately blue lotuses, flowing with their long sharp petals and bluish white seed pods. Shwoosh! — there was a big swish in the water that rippled near the center of the pond, where a carp or a catfish had caught a fly next to a shadowy reed bed.

Rrroork! — then she heard the low croak of a bullfrog. She looked over up along the right edge of the pond, where she saw him croak again, his throat expanding like a bubble, quavering out, his round flat ears like skins of a drum — Rrroorm! Rrroorm! Rrroorm! His call was loud and guttural. He had big eyes, filled with yellows and browns and maroons in his irises, his eyelids shuttering and reopening quickly. Rrrrimm! Rrrrimm! Rrrrimm!

Greil looked at him across the darkness, amazed by the droning girth of his low ribbit song. His face was blue with black dots running on his forehead and down his bumpy back, where his hind legs and torso turned a soft green. His throat and underbelly were pale, and as he watched her, he took deep panting breaths, his hands splayed proudly on the ground.

“Carefully now!” said Halk, whispering to her as he dropped his rain shield, kneeling closer to her right ear. “Patience, my lady, don’t scare him. That frog is no ordinary frog. He is the herald of the court. His name is Boswan. He is welcoming you.”

“Hello, Master Boswan,” she said softly, remembering her manners, as she went closer to the bullfrog, moving into a small clearing among the tall grass, next to gnarled willow roots and drift wood, smoothed pebbles and rocks. There was a patch of dark soil and moss, and thereupon she saw a procession of insects and animals. There were ants carrying dandelion seeds. At their front was a large stick bug with long craning legs flanked by a guard of grasshoppers. Behind them were two lines of ladybugs, some blue, some red. Each was flanked by shield bugs.

As they marched in, she half-expected to see a palanquin carrying Lord Beetle. But he was a gentle thing. He did not lord over his court. There, behind the lines and phalanx of courtiers emerged a big scarab with three long horns, six legs and a head and carapace that gleamed in a multitude of hues. Behind marched two tortoises, not big, but titans among the court, with snails on their backs, and a panoply of bugs doing what looked like a ceremonial dance.

It must be him, she thought: Aratarasu walked up toward Greil, then stopped, and lifted his head and his two front legs. His body gave the glint of an ageless eye. It threw up new colors and shapes from wherever she moved her gaze, each angle transforming into a new surprise. From here, at first it looked like oil on water. From there, it looked like a chorus of angels. Rainbows spilled off him onto the ground. He was indeed a living gemstone. This was the Walking Gem that Halk spoke of, an oracle ancient and inscrutable. And amid all that restless reflection, his two eyes rippled deep down with black wells of memory.

“I am Aratarasu,” she thought she heard him say, but it sounded as if it was coming from far over the mountains in the form of a whisper, a voice that flowed low like the breeze. “I am the Lord of Dreams.”

A light wind rustled the grass and the trees and the pond, its little dark waves with rims of light pushing up against the wet shore. She looked at her shoulder and she saw Halk bowing down, his antler-antennae pointing at Lord Beetle. Then she heard Sir Moth’s voice, but it too seemed like it was coming from nowhere. “Now, we must go,” he said. “Off to the Land of Dreams, and the Setting Sun.”

For a moment she thought perhaps she had lost her mind. She had never heard of Lord Beetle. Yet in her training, the shaman and the shawoman had also told her about the Great Hollows, the Starkness, and the Haarynns. They had warned her that the world was cracking like ice as the glaciers retreated. They had taught her about moths and metamorphosis, and told her before her sojourn in the Uplands, that she might encounter great masters. She had thought they meant perhaps a bear or bitter cold. They too had their secrets. Did they know of Aratarasu? No. Something told her ‘no’ and know — that she had to find out for herself.

He bowed his head down now too. Then his front legs carved a circle in the dirt as his hind legs pushed to help him dig deeper. She looked into his eyes, which were speckled with tiny points of light. In them, she thought she saw many phases of the moon and what looked to her like cities of stars, with the comet Razakusa cutting a circling line, worlds within worlds within worlds, eternally drifting.

He finished the circle, then started another circle inside the circle. Then the walking stick came up, striding and carrying a reed stalk. The phasmid started helping Aratarasu, digging another bigger circle outside the first circle. “Ranharrow!” she heard his name called. “That is Ranharrow,” said Halk.

To Greil, the circles looked perfect, one inside the other, before they started to bend like the ripples in the pond. As she looked at them, the little round ditches started to glow brighter and brighter, little dunes of dirt casting shadows, wind blowing dust off their tops, light adorning Aratarasu and Ranharrow, making their faces a beguiling mix of eyes, mouths and noses, like ghosts of smoke in marble, yet shifting in the fluttering light.

Then the pond began to stir, its waters lapping on the roots and against its pebbled muddy shore, swirling over logs and rocks with growing force. Its lily pads bobbed and fen reeds yawed with the circling gusts of wind, grasshoppers clinging to the reed’s tall leaves and rush tails. Frogs leaped high into the waves, shooting out their long tongues as flies zipped about in unrest. Catfish and carps glug-glugged water spiders that tripped in the whooshes of the surf. Dragonflies darted here and there, in triangles of air.

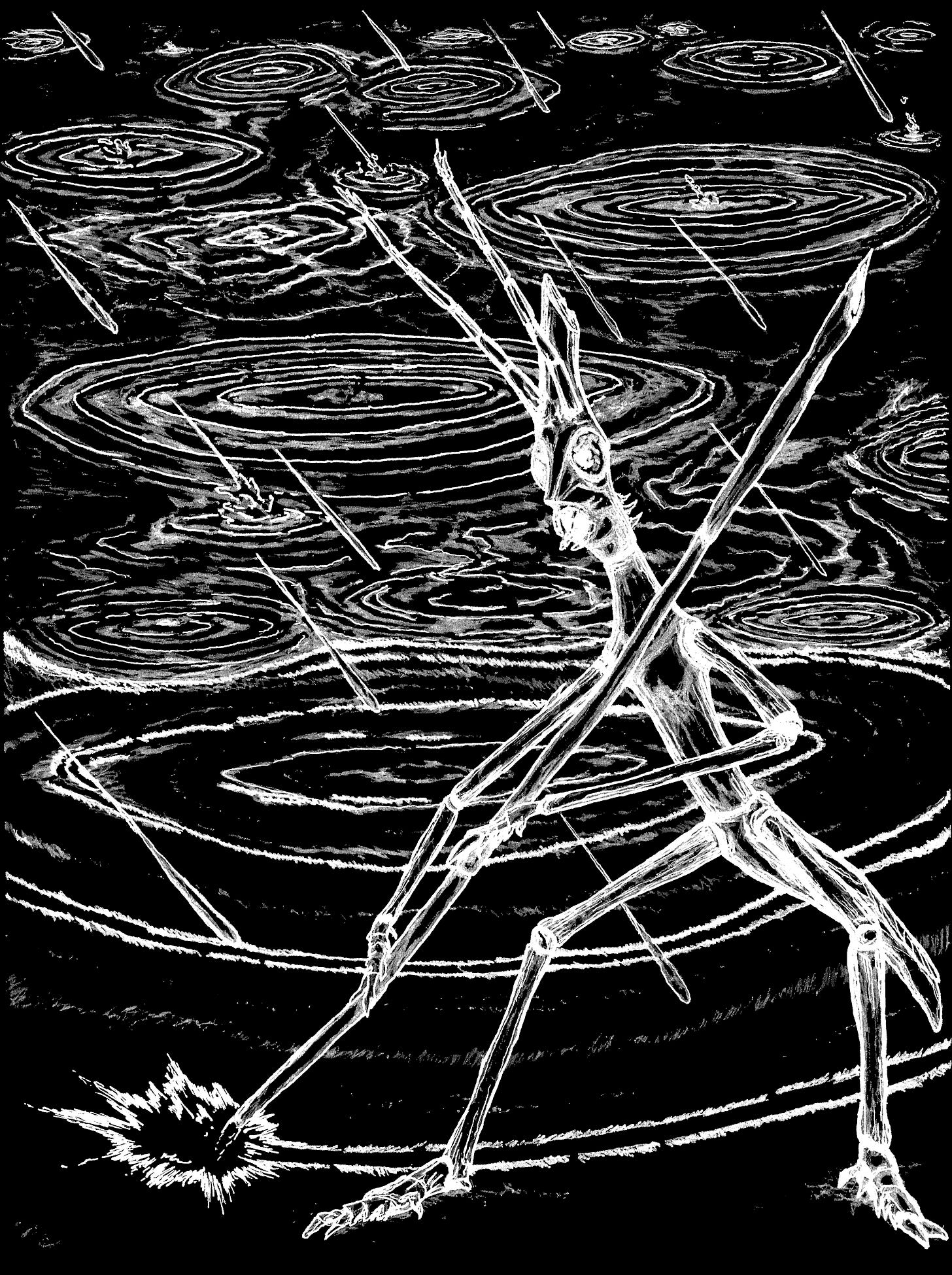

And then Greil saw the three circles of light pulse outward across the earth and the pond until everything slipped under a tide of shadows. She felt little Halk on her shoulder but weightless herself, as if she was floating in water. Aratarasu was at everything’s center, the eye of the storm.

“Bless you, Sir Ranharrow,” she thought she heard Halk say to the twig-man who stood by Lord Beetle’s side, his voice a swish-rush of countless reeds and ripples. “Even after countless years, drawing circles is never easy. But you do it happily.”

So here they could walk in each others’ dreams. Here, they could talk and they could see what was deepest inside her dream. Here, they came right up to what could not be said or thought.

“Here you see three rings,” Halk said to Greil. “Inside the smallest one is memory, all you see, hear and feel. The next ring is all that exists, what is known, and unknown. The third ring is dream. Without it, there is nothing, not even thought. The great spirits gave the Ovyrrakrúsk dreams to keep, and with dreams, we could grant wisdom. We nurtured scryers and prophets. In the starkness, we became Dream Keepers, and others became Shadow Keepers — the Fáta we are called. And the Fáta pick among the living those ready for the banshee’s call, to wander and seek the very bones of time.”

As he spoke, she found that they were walking inside a glacier, an ice cave of glassy shimmering blues, with meltwater dripping from its ceiling in little peaks and spikes, like a hive of ice. She heard water flowing down one of its tunnels, and following its sound she came upon a stream that flowed down from a tall moulin, a chute of sunlight coming down, sending glimmers here and there, her own shadow melting and squeezing along its wet crystalline walls and alcoves.

When she came upon the winding current, she saw a red leaf float down it and across her tunnel path, the water cutting right across it. “Every age is a leaf floating on water down a winding stream, the ripples of time moving it up and down,” she heard Halk’s voice say. “For memory transforms into history, as each new leaf sinks or drowns. Yet some leaves are ferried back to shore. And some lives are reborn.”

She nodded in silence, as another leaf passed on. But when she looked up, she saw standing still on the other side of the stream, Aratarasu, who was gleaming black with steam rising from his belly as he breathed. Behind him the tunnel continued. He turned and walked up its snowy floor and up a little incline in the path and down through an arch that looked like the ribs of a giant mammoth. Following Lord Beetle, she and Halk went over the little hillock, and down into a big wide cavern where she saw what looked like a massive ice-covered lake.

Dun-dun! Dun-dun! — she heard a deep resonant drum coming from underneath the reservoir. Light seemed to dance up and glance off the vaulted glacier hall. A play of shadows and shining beams dazzled her eyes, as she tried to peer down into its depths. It was pulsing, whatever it was. And then she saw it: a big dark shape ploughing through the lake, a shadow that was not a shadow. It was swimming her way and swooshed under her legs.

Then she saw its fluke, and it dawned on her that it was a whale. Stunned, she turned and watched it bank and spiral down. “At the center is the beating heart of time,” said Halk, his words washing away at the shores of her mind. Then she saw the three circles spinning inside and around her. She saw the sun and moon going round the ice hall. She put down her bow and perceived a drum. She gently tapped it — dun-dun! Then she saw a manor by a bubbling volcanic lake. She went inside and it had countless doors. She opened one and saw the Beetle’s shadow on the wall. No rain. No lightning. This is where he was.

“Kyvaliya,” she whispered, before straightening from her bow. The manor and the volcanic lake disappeared, the three circles faded, and the ice cave receded away. His procession started to depart, one by one, as the turtles stood guard, waiting for each courtier to pass back into the forest. The rain had stopped. She heard now the soft marching of their many feet, and the music of drips of water from the trees above, the little plunks into the pond, and the plops on the fronds. Ranharrow the stick-mantis bowed and turned to withdraw.

An image came to her then: a grove of rosewood and a great jut of malachite at the other side of the lake on an island that she had long known. She would go out to it, she thought. Thick swarms of fish she would find across the water that she could catch for the days ahead. She would take some wood to carve and some green ore to etch. She would search for the heart of it.

The breeze again rustled the grass and the leaves and the shore. Halk too came back out of prayer. “We are here and not here, but now you have the Vision,” the Moth said, as the shadows wavered and the wind died down.

She wondered what exactly she had gotten herself into, as Lord Beetle stirred. Rryrrinn! Rryrrinn! Rryrrinn! — went Boswan as Ranharrow strode on.

“Yes, Lord Aratarasu,” said Greil. “I will go there. I will follow the sun.”

“Bless bright night and day,” said Halk. “Go then, and run-run.”

Then the Beetle bowed, turned and was gone.

Thus concludes the second chapter of the Aphantasia Trilogy: Where No Thoughts Go, an original epic fantasy work by T.Q. Kelley. You can read about its intent, mission and musings here. We will be self-publishing future chapters to book one, The Low Owl (most will be free), and short stories (which will be for paying subscribers) here at Wraith Land. The first chapter is here.

Copyright owned by T.Q. Kelley.