The Art of Jay Johnstone, Part One

What happens when a Tolkien artist paints from inside Middle-earth?

In 1912, the influential psychologist Carl Jung published his most famous work, Psychology of the Unconscious, where he identified the power of the psyche — to imagine — with the power to live, and the will to power as the lack of love, one the shadow of the other. “The dream is a series of images, which are apparently contradictory and nonsensical, but arise in reality from psychologic material which yields a clear meaning,” he proclaimed in its first chapter.

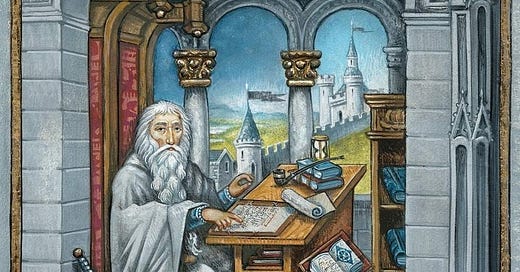

In 2020, the Tolkien Society awarded Oronzo Cilli their Best Book designation for the year. Tolkien’s Library: An Annotated Checklist is a painstaking bibliography of J.R.R. Tolkien’s personal library, an attempt to excavate the reading interests of the renowned professor and author. Gracing its cover was a startling image of Gandalf painted in the style of medieval art by the UK artist Jay Johnstone — perusing scrolls, the wizard searches for the secrets of the One Ring.

The magic of “Gandalf in the Library of Minas Tirith” is its stark sense of a dream within a dream, what looked like an artwork made by a painter who actually lived inside Middle-earth. Inside that dream, inside that book, on page 138 near entries for James Joyce, was evidence that Tolkien, the master of dreams and modern fairy tales, owned and presumably once read Jung’s breakthrough book deconstructing dreams and interior fantasies. Like Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, published about 40 years later, Jung’s Psychology of the Unconscious was an epochal work. It changed how many perceived the landscapes and shadows of the human psyche.

Johnstone dreams in Tolkien. And through him and his artwork we can perceive anew what it would mean to live in Middle-earth and to create art inside it. While Tolkien himself made “sub-creation” the purview of his own characters, from the creation of the Silmarils by Fëanor to the writing of the Red Book of Westmarch by the hobbits, Johnstone imagines what it would be like to be a painter inside Tolkien’s world, and then paints that world and its history. Reminiscent of the religious medieval icon paintings by Duccio di Buoninsegna and Fra Angelico, Johnstone’s paintings work not just like dream portals but time portals.

They came from a “troubling dream” he had in 1999, Johnstone tells us in his book, Tolkienography: Isildur’s Bane and Iconic Interpretations, published in 2018. “The dream began with a funeral in a small torch lit stone-built church,” he writes in its introduction, recounting how the dream was a nightmare about losing his wife and how he tried to escape his sorrow by fleeing her funeral.

“The choice was out the main arch door on my right or through a doorway leading to a corridor on my left,” he writes in detail. “For no discernible reason I chose left and found myself wandering a deserted monastery. It contained all the religious relics, art and paraphernalia you would expect, but they were wasted on me and I ignored them in grief.”

Here in the deserted monastery, Johnstone encountered what one might interpret as Jungian archetypes. First he perceived them as Christian icons: Jesus, St. Peter, Moses and very strangely, one of his wife on an altar. Yet it was not his wife, he realized, but a character he was deeply attached to. And the mystery of why this Christian iconography mixed with his own mythography, sparked a revelation.

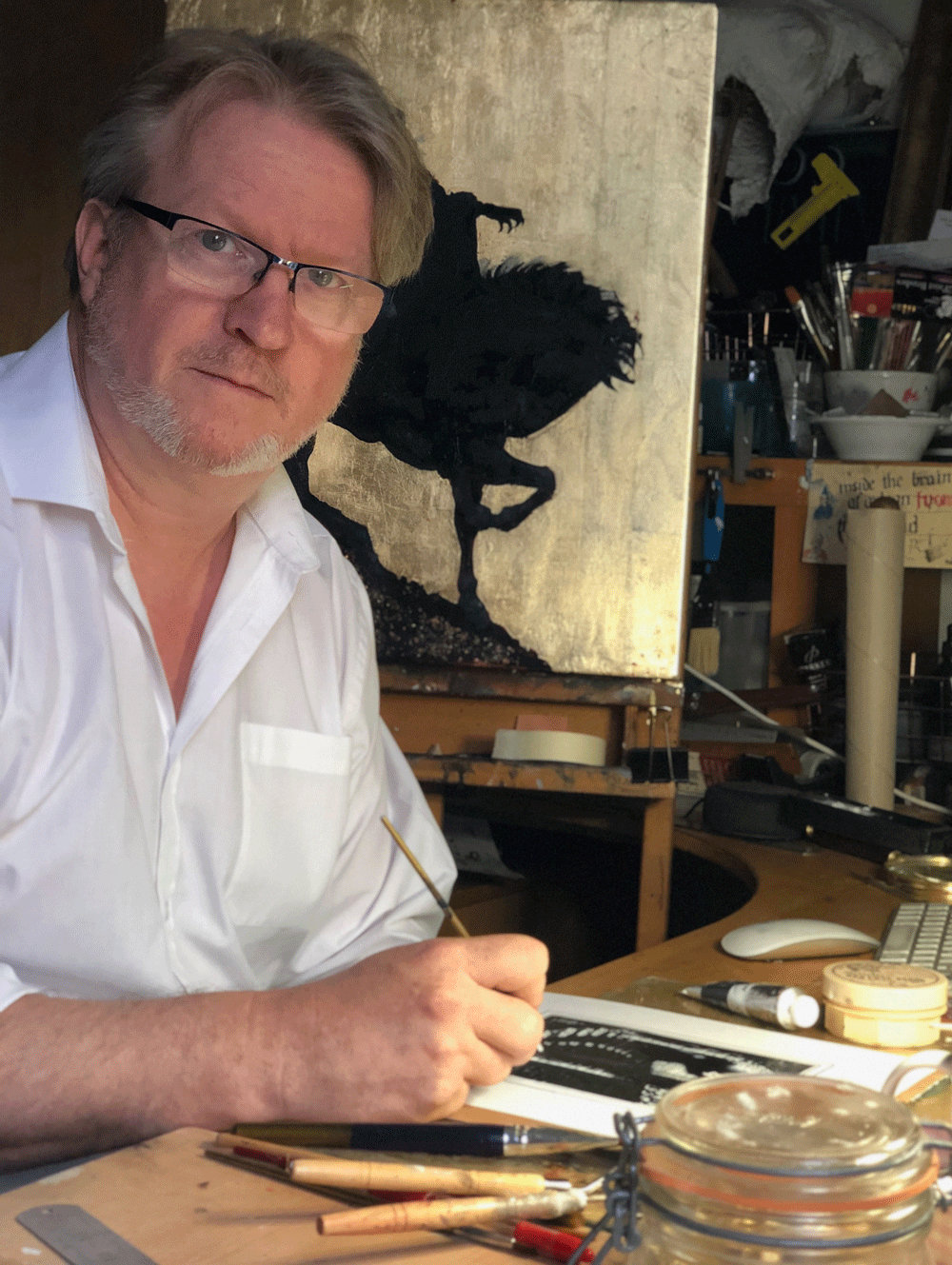

I first learned about Johnstone’s extraordinary art through TheOneRing.net, and was intrigued by its metaphysical implications. After reading a scholarly review of his art book by Lance A. Green in the Journal of Inklings Studies via the Edinburgh University Press, I purchased it, absorbed it, and reached out to Johnstone for an interview. Over the course of two hours in early 2021, he kindly took me through his artistic journey and the new roads of mythic inquiry his artwork has opened.

“This came about because of a very bizarre dream in which I was in a Celtic Scottish church,” he says. “And I had seen a lot of what I believe to be Christian iconography. But on closer inspection, the iconography had such a connection to Tolkien's work. So when I saw pictures of Jesus, they were initially presumed to be a Christian icon of Jesus, but I saw it as Aragorn. I looked at Moses and saw Gandalf. There was a great connection between the images that I saw and the beliefs that Tolkien had, and it came to me literally in a dream.”

“Did Tolkien use these icons from Catholicism as foundations for some of the core attributes and personalities of the characters?” he wondered, recalling his thought process. “And once I made this connection in this dream, I literally the next day started to paint a particular piece called ‘The Halls of Théoden,’ which was a manuscript, which again, was just a copy that I saw in the dream of a book of an artist’s illustration, that I realized who the characters were, and I couldn't read the words, and I realized the text was in Tengwar.”

Also, he noticed some script around the golden halo of the woman he had thought was his wife. While he could not decipher it, he recognized it too was in Tolkien’s Elvish script, Tengwar. That’s when he realized the icon of his wife was Arwen, daughter of Elrond and Celebrían, granddaughter of Galadriel, loyal partner to Aragorn, and the future queen of Gondor, following the overthrow of Sauron.

In many ways, what started with the Peter Jackson films — the extension of Middle-earth into what is called the “metaverse” these days, in other words, the theater of immersion — comes full circle with Johnstone’s “meta artwork.” Not in terms of video games or VR, per se, but in terms of the set designs — including Alan Lee’s painting of Sauron bearing down on Isildur — and intricate props that allowed Jackson to film “inside” Middle-earth. The landscapes of New Zealand of course did most of the immersion, but it was Weta Workshop’s attention to detail, including the art, artifacts and architecture inside the world, that also transported audiences into Bag End, Rivendell, Moria and Minas Tirith.

Long before the movies, the artwork of renowned Tolkien artists like Alan Lee, John Howe, Ted Nasmith and the Brothers Hildebrandt, gave us a sense of what it was like to be in Middle-earth, to look on it with our own eyes through their eyes. But Johnstone’s vision is something different. It wholly immerses us in Tolkien’s world by asking us to consider the subjects of his stories as subjects from within their world, imagining what a painting of them by a painter in Middle-earth who is closer to their era, perhaps living during or just a few generations after, might actually look like, at once creating a distance between us and the past, but simultaneously collapsing it, so we can see them anew as something holy.

Johnstone is not a church-going Christian. While he believes in God, he resists prescribing to any one church or religion. But one could say he is pious about the things that have moved him. The artistry found in the medieval churches and iconography of Europe moves him deeply, as does the artwork of his favorite painter, Gustav Klimt, which is perhaps where Johnstone also channels some degree of eroticism, exoticism and heady symbolism into his work. But the sacredness that informs much of his oeuvre, the holy iconographic style he references from the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Church art traditions, evidenced in the frescoes, duomos and altars of their many old cathedrals, synthesizes Tolkien’s mythology with Christian mythology into a modern sublimation of the collective unconscious and into clearer meanings.

And what is that meaning? Well, Tolkien’s work, from The Silmarillion to The Lord of the Rings, is deeply spiritual in nature. Masked as adventure and child’s play, it is in fact almost liturgical in its many rhythms and hymn-like trances of thought, a biblical work for the secular world and the technological age. That’s what Johnstone’s work brings to the fore and to a razor-fine point. While the ur-Christian iconography of the Middle Ages undergirds his images, the truly powerful nature of his contribution is what one might call the worldly.

One of the anchors of Johnstone’s worldly approach is his research. Coming up in an era of prolific scholarship on Tolkien and his work, he has more historical and theoretical grist at his fingertips. Tolkien’s experiences in France at the Battle of the Somme in World War I is particularly important to Johnstone, who has spent time with John Garth, the author of the acclaimed Tolkien and the Great War, which was the first in-depth account of the author’s wartime travails. Such research often inspires his art, sourcing its emotion as much as his dreams.

“I got very hooked on the War and spoke extensively with John Garth, about Tolkien's experiences during the War,” he says, connecting the Nazgul and the Dead Marshes back to the very first warplanes. “I'm really interested in where he got the inspiration, where he got the primeval fear and emotion from, so I wanted to explore that. During the War, the biplanes used to fly over the battlefields and look for troop movements. Most of them didn't carry weapons because they were spotters and they were basically directing artillery guns onto troop movements. So to be seen by the planes was to bring down death.”

The European roots of Tolkien’s mythology is inescapable. But its promise is also beyond borders and even history. It appeals to people around the world, as do the cathedrals of Europe, from Notre Dame to the Hagia Sophia. Art transcends. And it is the Asian and African undercurrents in some of Johnstone’s Tolkien works that bequeaths a more universal and timeless quality to his icons than one may presuppose when encountering the more superficial elements of his many brush strokes: From world wars to Tolkien’s own vigorous engagement with the profound, Johnstone’s worldly style cleverly expands the canvas.

Klimt, for starts, was greatly influenced by the gold leaf ornamentalism of the Rinpa School of art and the lacquerware of Japan. The subtle but vivid eastern and southern waves in Johnstone’s artwork can be sensed in the Byzantine and Coptic stylings, including the almost Russian and Turkish vibrations in some of his icons, especially his renderings of King Théoden and the Levantine-toned depictions of “The Council of Elrond,” as if the Renaissance that was in great part triggered by the Crusades and trade missions with the Far East had similarly influenced Middle-earth painters soon after the War of the Ring.

That is, we can imagine a world that was just changing and just beginning to usher in the Christian — a cultural and theological explosion that began in the Middle East, between Europe, Africa and Asia — and the modern world as we know it, however slight the angle. Theology is inseparable from history. So it is the same with delusion. Mythology is what allows us to rethink and reshape both history and the delusional into truths and fantasies that yield new meaning.

All art is essentially mythological. It is not just the thing it is representing. There is a dislocation of sorts, the interpretation of the artist and the receiver of the art, from the flight of the imagination to the search for truth. And perhaps what is most inspiring about Johnstone’s Tolkien art is that he boldly confronts the nightmarish dimension — the shadow — of the author’s psyche and vision.

When you talk with Jay, you immediately recognize his humility and gentleness. He has a calm English accent and is welcoming at all times, ready to discuss the philosophical as well as the personal, from the funny to the tragic. You could say he is very Tolkienian in that way. But the trait that seems most central to his worldview is compassion and forgiveness, both of himself and others. In his Tolkienography, this is especially clear in his reconsideration of Isildur.

The book includes a learned commentary by Thomas Honegger, a Professor of English Medieval Studies at the Friedrich-Schiller-University in Jena, Germany. Honegger saw the revolutionary meaning inherent in Johnstone’s interpretation of Tolkien’s characters and stories; he credits him with changing how scholars perceived Isildur because he asked the question: could the fallen prince be considered worthy of sainthood? For Johnstone, the answer is yes.

I don’t want to spoil Honegger’s detailed analysis — you should read it here or purchase Johnstone’s limited edition of Tolkienography: Isildur’s Bane and Iconic Interpretations — but the broad outlines are stark enough to convey the thematic breakthrough uncovered by Johnstone’s dream and artwork. For starts, Johnstone wondered why exactly he was headed north along the Anduin from Minas Tirith after he had defeated Sauron and had taken the One Ring to safety. In essence, Isildur did not feel safe, as the burden of the Ring grew ever more painful. In a desperate dash, he tried to bring the Ring to the Elves for wiser keeping.

This alternate version of Isildur’s corruption and redemption was first presented in Tolkien’s Unfinished Tales in “The Disaster of the Gladden Fields,” where we learn that Isildur struggled with his refusal to destroy the One Ring in Mount Doom. In a kind of repentance, Tolkien proffered that perhaps Isildur was no simple turncoat. In fact, Tolkien experimented with the idea that Isildur had redeemed himself by relinquishing the Ring, aided by luck or providence. Johnstone’s dream raised this same question, for the painter wondered: Temptation had undone Isildur, so why would he see him in a church?

“The manner of his death becomes really important because I thought, ‘Well, he's got to die,” reasons Johnstone. “If he lives, he becomes another Sauron. But he's a good guy. He's done all these really good things. The gods have blessed him. The gods have saved him. The gods have protected him.’ He's done great things for the survival of his people. He's done great things for the survival of the White Tree. But really, the only way he's going to lose the Ring now is if he dies.”

In a conversation in 2013 with the Tolkien Professor, Corey Olsen, the question of whether Isildur deserved a halo in his icon painting — which was what Johnstone had seen in his dream — came to the surface. Following the logic that Isildur had to die, they wondered if he was then a martyr. “Was it Divine Providence that put him on the battlefield?” Johnstone asked himself, because he had already made the connection between picking up the broken sword, Narsil, as almost like picking up the Cross.

So picking up where Tolkien left off, Johnstone completed the picture. In his reckoning, the only way Isildur could escape the Ring was in a way to sacrifice himself. Ambushed by Orcs near the Gladden Fields, he dove into the waters of the River Anduin where its currents slipped the Ring from his finger. Tolkien’s narrator suggests that Isildur was in fact relieved of its loss right before he was killed by poison arrows. Johnstone’s iconographic oil painting, “The Death of Isildur,” captures a serenity not often associated with the fallen king.

And the key insight Johnstone brought to this turning point was a hunch that the Anduin was not simply the scene of a crime, but a baptismal deliverance of the Ring from the servants of evil to Sméagol, and eventually Bilbo Baggins. In the painting we see water spirits surrounding the body of Isildur, servants of the water god Ulmo, who had long guided the faithful through darkness to light: Ulmo leads Turgon to the hidden vale where he builds Gondolin; he brings Eärendil and hence Elrond and Elros into the world; he helps deliver the Númenórean Faithful safely to the shores of Middle-earth.

“Then the question became, if he's fleeing across the river, if he's gone across the river, and then the line in the book says, ‘and the Ring betrayed him,’ and when I spoke to academics, they all said if the Ring betrayed him, it was with malice,” he recounts. “It fell from his hand, and therefore he was revealed to his enemies and killed. I thought, ‘Well, actually, that could mean something completely different.’ And the step change that I came up with within the Orthodox Catholic society, is that to remove sin, you have to be baptized. If somebody is baptized, the sin is literally washed away.”

“And now if you think of it that way, it became a ‘cloaking device on a starship’ story about the Ring,” Johnstone continues. “It betrayed him by falling off, not by maliciously leaping off, but lost its power, grew to its original size, and fell and he was betrayed, and therefore is peppered with arrows. He sinks in the water and he comes back up once, and then his body is taken, and then I thought, ‘Well, Ulmo was in the water and almost always protected him.’ And so therefore, the manner of his death was crucial. And with all these thoughts, I decided he does deserve a halo. He was martyred for the cause. And he was on the field at the final battle through Divine Providence.”

In his iconic painting, “Isildur’s Bane,” that beatification of Isildur is explored through the stylistic attributes of Orthodox Christian iconography, bringing a Near Eastern touch to a primarily Western inspired mythos. The visual language of Orthodox Church icons from pre-Renaissance times, Honegger argues, is an ideal vessel for this temporal and thematic realignment. The cultural influence of Constantinople made its way throughout Europe even to the British Isles in terms of its aesthetic renown. Johnstone’s use of golden halo discs, typography arrayed above or around, the slightly turned gaze of his Middle-earth saints, the cracked veneer, the emphasis of a pious mood over realism, recasts Isildur as both an enigma and magnifier of moral study and insight.

In fact, it is that holy tenor that gives these works their realism. It is that triangulation of historical and cultural angles that allows us to follow Johnstone into his dreams, and hence Tolkien’s Middle-earth, as if we too were walking the halls of that torch lit stone-built monastery. Which brings us to what I believe is one of his most powerful images, “Gandalf the White,” the mesmerizing image of a holy man if you like, weathered, serious, determined, monk-like in his posture, a bulwark against temptation and condemnation. Here is a figure who has seen things, mourned things, and has walked the fire of existence. The deep blues bestow a nocturnal, misty, Northern ambience, pulling just so away from the Southern, while the red-rimmed, spotted rays of a sunny halo hint at his holy rebirth as an emissary of the Flame of Anor — the Flame Imperishable.

Like Gandalf’s Ring of Power, Narya, the Ring of Fire, which is only revealed in the last chapter of The Lord of the Rings, there is a lot that is unseen in Johnstone’s work. The deep research is layered underneath. The theological complexities of his motifs require theological awareness to unveil their deeper meanings. But deeper still is his great love for Tolkien’s humanism. All of these elements are sensed and felt when observing his work. Even if one misses some of its slyly arcane and religious allusions, their shimmering depth means one can also continually uncover new reflections in these mirrors of the human spirit.

It’s not just the reflective effect of the gold leaf in his paintings, but the emotional intelligence glinting in every stroke and dot that constitutes his art. So that again, after talking with Jay, I came away with the sense that his love of Tolkien is just as personal as it is philosophical or theological. This is the common bond that links so many to Middle-earth, that it is a kind of universal prayer, a sermon about the survivability of tragedy and hardship.

Johnstone highlights his relationship with his son, who has had to make his way through difficult learning and mental health challenges over the years. Johnstone has felt guilt and pain over his past inability to understand and later to fix or ease some of those challenges. But in general, through art and Tolkien, he has found a way to unlock greater healing and love between them. For them both, Tolkien’s stories and life constantly inspire: he has even painted part of an exploded WWI artillery shell with Tolkien’s wartime photo portrait; and combining all of these threads, he has also painted a crossroads of sorts between the three of them.

Tolkien’s Leaf by Niggle story, and its theatrical interpretation by Richard Medrington’s Puppet State Theatre Company, was one of Johnstone’s favorite subjects to translate. In his painting, “The Voices,” he brings Leaf by Niggle, the hobbits of Middle-earth, Tolkien’s battlefield trauma, and his and his son’s own self-persecutions into focus. The story was written by Tolkien as an expression of fear and a deep sense of failure over his struggles to finish The Lord of the Rings. Every artist deals with self-doubt for every human being deals with self-doubt. Metaphorically, Tolkien described this both through the image of a tree that Niggle never seems able to complete, each branch and leaf pulling him away, combined with an autopsy of Niggle’s body and life by two doctors.

“They're discussing him in a past tense and they're talking about, Well, he was a great parent. He was a fantastic painter,” Johnstone explains, alluding to the legs and feet of two hobbits in the painting — Frodo and Sam, as the doctors — who we cannot see from the waist up. “And then the second one says, No, he's a waste of time. He never created his masterwork. And so they have these two voices arguing and so this picture is called ‘The Voices’ — and the portrayal is actually of my son.” Thinking more on it now, I realize it is also Gollum. “This covers three or four things for me,” says Jay. “It was Niggle. It was obviously the story about Niggle. But to me, the voices weren't doctors. They were actually angels.”

“They were almost the gates of heaven,” he theorizes about the two doctors, and Frodo and Sam by extension through his painting, both standing over his son in judgement, with only the hint of compassion coming through the pastoral hair on their hobbit feet. “Saying, Well should he come in because he's a good guy? Should he not go in because he is a complete failure? And that's how Tolkien viewed this I think. But that's also how I viewed it….It's my guilt that I should have been a better dad, but I'm actually a failure at the same time.”

Interestingly, Tolkien wrote Leaf by Niggle from 1938 to 1939, before it was published by The Dublin Review in 1945. He started The Lord of the Rings in 1937, struggling to find his way forward — writing it was like waves on a beach, it has been said. Leaf by Niggle’s inception coincides with the run-up and outbreak of World War II, and did not reach readers until the end of the conflict. There are fascinating coincidences and symmetries here. For one, the connection Johnstone has made between the two doctors and the two hobbits, well, actually, the three hobbits, for Sméagol’s self-persecution is perhaps Tolkien’s greatest literary masterstroke as a storyteller, is the tension between the voices of Gollum.

“So I always have these two voices in my head,” Jay continues, pointing out the symbols and secret histories hidden or lovingly tucked into ‘The Voices’. “And so behind here we have poppy fields, the soldiers marching, and over there we have the German guns. So again, it's by reference back to Leaf by Niggle, and so some of it’s linked back to Tolkien. And there's the Niggle tree sitting in the center of it.” Tolkien would finish his epic masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings, in 1949, after he exorcised some of his fears in Leaf by Niggle. These were anxious years, and one can imagine that Tolkien wondered what the future held, and if his fantasy was relevant, or a fatuous self-indulgence, or if he had the courage of heart to even finish it. And so we can see Tolkien himself in Slinker and Stinker, in the two hobbits, the two doctors, in Gollum, in Johnstone, and in his son.

“So the paintings have a lot of stories and a lot of meanings in them,” Johnstone says of his Tolkien art. “Because I do think within Tolkien's works, it does if you read it, they're almost biblical. They have such relevance to your life, that I find really deeply touching. And so I keep playing with these ideas. I do like a lot of Tolkien art and I think a lot is fantastic. It's so inspiring. But what I try and do is get down to the emotional level, and trying to ignore most of the films, and I think back to, how did I feel when I read the books for the first time?”

So Tolkien’s voice, and the voices of his characters, speak to us almost like hallucinations in a living dream, or even madness. The chaos of life, the paradigm shifts of tech, the unspooling of the post WWII order, the crisis of loneliness in a hyper-connected age without lasting empathetic meaning, shakes the beams and columns of our global 24/7 matrix. Is it any surprise that Middle-earth calms and appeals to so many, with its illusions of a simpler time and place? And yet what is surprising to the adult in us, is that the voices we hear inside it are both timeless and endlessly complex: cathedrals of imagination and recovery, and mystery, and yes, even faith, that captivate the well-meaning, and the astray. So that we get the sensation that we’ve been here before.

When we think about the cataclysms of the 20th century, from the Spanish Flu to the World Wars, it’s hard not to ask whether we are living through a Jungian cycle or archetypal whirlwind. Prof. Honegger has pointed to the Jungian implications of Middle-earth with his essay, More Light Than Shadow? Jungian Approaches to Tolkien and the Archetypal Image of the Shadow, teasing out the thematic possibilities of a Jungian reading of Tolkien’s fiction.

Honegger has also found evidence that Tolkien must have been familiar with Jung or read his works. In an academic visit to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in 2006, he found in Tolkien’s notes for his famous lecture On Fairy-stories that Tolkien had written down a list of authors and scholars to mention. Among them was “Jung,” and elsewhere “Jung Psych of the unconscious.” Quoting Jung, Honegger believes Tolkien perhaps omitted him to avoid biographical over-analysis:

We can therefore be grateful that Tolkien refrained from using his tales and stories as “therapeutic tools” and treated them as works of art… [They] fulfill one of the functions of art, which Jung, in an essay written in 1922, defined as “educating the spirit of the age, conjuring up forms in which the age is most lacking. The unsatisfied yearning of the artist reaches back to the primordial image in the unconscious which is best fitted to compensate the inadequacy and one-sidedness of the present.”

In many ways, it’s a miracle that Johnstone’s dream visions of Arwen and Gandalf and Aragorn, and his intricate symbolization of Isildur and Gollum, so naturally fit and fire a new dimension of Tolkien’s mythology. More so than probably any other Tolkien artist, he has managed to move his absorption and appreciation of Tolkien’s story and characters into truly different territory, a territory that is at once alien and convincingly within the meta-world of Middle-earth. Johnstone’s yearning and yielding of new forms, his conjuring of a holy house for beloved Tolkienian characters, reconnects us with a primordial light, and its shadows.

While meaning gets its power both from its specificity and its interpretability, even its mutability, dreams are on their surface powerful because they are at first experienced as an interface with the present, so often a bombardment of images, sounds and motions that are meaningless save for the sensation of consciousness. Only so much can break through moment to moment when we are awake, and so it is the same with dreams. Yet in dreams, there are cracks of contradiction that we fall through, things that defy physics, time and even logic — the psychologic.

Tolkien explored the personal and collective unconscious through language and most importantly through mythology, and then fantasy, the story form most like dream, yielding clear meanings. Like dream, art is at its best when it transports us. The so-called flight from reality. And yet, that our minds can drift through space and time and out of our bodies, makes no sense. Until it does.

“I still find it difficult to claim any credit for their creation,” Johnstone writes, drawing a line from his unconscious to a series of iconic images that illuminate Middle-earth. “To me, they are but copies from dream paintings.”

Our consideration and conversation with Jay Johnstone continues in Part Two, where we deep dive into his illuminated manuscripts…