The Art of Jay Johnstone, Part Two

What happens when Tolkien's Middle-earth tale becomes a holy script?

It came to him in a dream — a monastic dream. One with runes and secret meanings. The Middle-earth art of Jay Johnstone is not simply one of imagery, but one of letters and words and scripture too. Like a monk, Johnstone, who lives in northern England in Newcastle upon Tyne, just miles from Jarrow — the old home of the Venerable Bede — brushes an inky magnificence and meticulous manuscripts that illustrate the world of J.R.R. Tolkien like never before.

He invites us to ask the question: What if we opened a beautiful Red Book of Westmarch, a bible by Bilbo and Frodo — but re-scribed and ornamented many years later by friars and nuns of a Gondorian variety, pre-Christian yet running in the same spirit of the Middle Ages? : By candle light, with inkwells and paints, and gold leafs, they recorded a lost age and lost world, a place of heroes and demons and wargs and dwarves and elves and trolls and hobbits, just on the edge of memory.

Johnstone, who was raised as a Catholic but does not subscribe to church or daily Christian worship, like his Tolkien iconography work — which we focused on in Part One of our series on his art — has drawn deeply from the religious and folk traditions of England and Europe to inform his personal vision of Middle-earth. Tolkien’s writings were grounded in sensibilities of the Middle Ages — its manuscripts constituted many of the ancient tales that inspired him. So manuscripts, illuminated manuscripts, form a natural bridge between.

While we often think of Beowulf as the foundational story — interpreted and recorded by an unknown “poet” circa 1000 A.D. — that Tolkien based his deepest scholarship on, he also derived learnings from manifold medieval English texts, including Pearl, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Middle English Canterbury Tales. The key thing to keep in mind here, and this perhaps requires stating in our “Digital Age,” is that these stories were all handwritten. They predate the printing press. They are manuscripts, i.e. written by hand.

Before the Gutenberg Revolution of 1454, for centuries, someone had to record oral tales — think Gilgamesh and Homer — onto papyrus, parchment and paper, and pass it down to the next generation, and on and on. Alphabets, letters, words and scripts had to flow from mind to hand, and hand to mind, through countless nights and endless work. The Gutenberg Bible was the first machine-produced book in the world. Before it was a long chain of labor, and artistry, that helped evolve humanity from a speaking-only species to a speaking and writing one.

These manuscripts were so valuable that during the Middle Ages they were often locked with chains to library desks, while many had metal clasps to protect them from light and dust. Making parchment, made from animal skins, the quills, inks, and binding, was incredibly laborious. In Europe, during the Dark Ages, after the fall of the Roman Empire, much of the scribing and illustration was the domain of Roman Catholic monks and nuns — Benedictine to be precise — and was carried out in scriptoriums, rooms in monasteries where scribes would read, copy and paint Latin scripts.

The illustrating of borders and scenes from the Bible, or Greek and Roman classical works, was called “illuminating” a manuscript. The “pagan” world did this as well, and originally set some of these methods in place before Christianity and the Church transformed access and distribution of earlier texts. In Asia, the earliest religious texts of Hinduism and Buddhism were originally captured on palm leaf and bamboo in word-form only. But more historical works like the oldest epic poem in the world, the Mahābhārata, which contains the 700-verse Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, were richly illuminated with imagery.

Johnstone has pointed his brush to this dank and dusty seam in our collective history, traversing the space between Tolkien’s stories as he wrote them, the way in which his characters may have lived and recorded them, and the more nebulous transference of those tales and tomes to a kind of monastic preservation. It’s as if Benedictine monks lived in the halls of Minas Tirith and religiously re-scribed the Red Book of Westmarch, as it came to them from Rivendell by way of the Shire, kept safe by Samwise Gamgee’s daughter, Elanor Fairbairn, and passed from generation to generation among the Wardens of Westmarch.

It’s that idea, consciously or not, that has sparked excitement among the Tolkien fans that come across Johnstone’s manuscripts. They are his most popular works. Originals and prints sell quickly and well. As a frequent guest and panelist at sci-fi and fantasy conventions nowadays, Johnstone originally was reticent about the Tolkien Society events that have now become a mainstay of his engagement with the Middle-earth community. His meta artwork — his sly medieval style — has helped Tolkien fans, scholars and artists imagine a deeper common ground.*

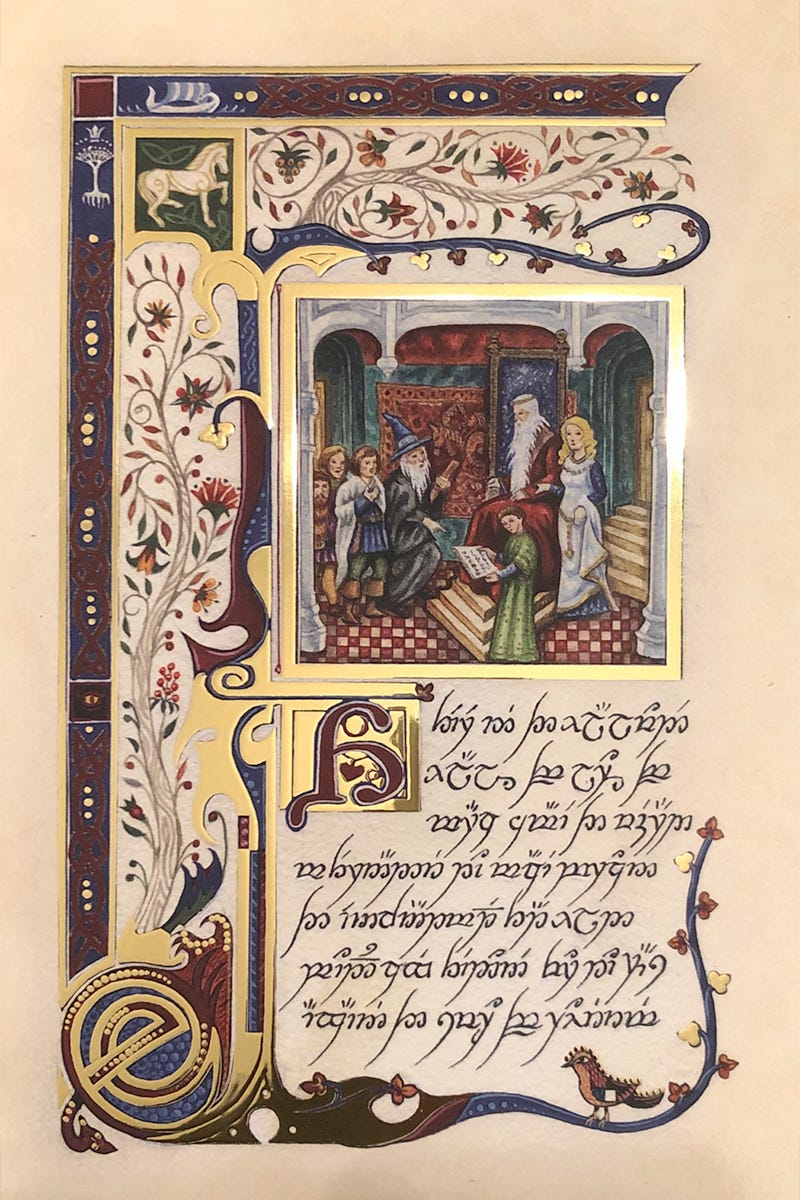

When I interviewed Jay last year in April, I asked him about this “text within a text” vision in his Tolkien art, which to me are of the same theme as his “dream within a dream” iconographies. Using his painting “Gandalf in the Library of Minas Tirith” as an example, I pointed out how he meticulously detailed the books and scrolls in that image with Tengwar lettering. You can also see this painstaking attention throughout, as in works like “The Dwarves,” which illuminates Thror’s map in Bag End from The Hobbit.

“You know, I can't remember what it says but there's two parchments on his desk and both of them are written on and the lettering is about a millimeter high,” he says of the Gandalf in Minas Tirith work, chuckling a bit under his breath. “It's absolutely tiny. I literally do it with a magnifying glass and a precision brush, a brush with one hair on it. I do that in quite a lot of paintings.”

It’s another level of getting inside Middle-earth, down to the micro. Such works are a celebration of the writers and sages inside that meta world, and of writing and learning itself. Johnstone’s “Círdan the Shipwright” — with its Tengwar and ship schematics on parchment — and his “Bilbo at the Library at Rivendell” — with history flowing from Bilbo’s pen — give us a new window into time.

“Just to hide stuff,” he says of the Bilbo in Rivendell manuscript, where a spider crawls on the ceiling, the Eye of Sauron emblazons a book cover, and the Key to Erebor sits at the hobbit’s feet as he sits on a river barrel. “In that one, there's 27 symbols of The Lord the Rings. It's hidden in the floor and everywhere. It's just got symbols all over the place. I enjoy doing that. I like to hide things — secrets.”

This bequeathing from quill to quill, is rightly given a very playful nature, not only because according to Tolkien, the original scribes were hobbits, but because Tolkien himself imbued much of his own writing with a deft dab of comic relief. I am not a medievalist nor a scholar of world religion, but I find Johnstone’s astute perception and dedication to meta historical detail in this regard absolutely sharp and convincing. It’s not that his Tolkien manuscripts are real — they are fantasy works in themselves — but that they negotiate the present with the past in a highly sensitive way, through a sprite imagination and a keen spirit.

Hence, he moves us from Middle-earth illumination to a Middle-earth revelation. His manuscript images tie the Tengwar and Cirth scripts together into textural landscapes that evoke a sense of time as less linear than we should believe. In “The King of the Golden Hall,” the flow of Tengwar letters runs underneath a scene of Gandalf and the Three Hunters at the throne of the aged Théoden, a worried Éowyn at his side, and Gríma Wormtongue reading the visitors what looks like a declaration of their non-rights inside the realm of Rohan. Curled around the body of the text and the scene are branches, leaves and flowers; a White Horse of Rohan gallops in a corner near a ship at sea and Aragorn’s heraldry — a coat of arms with the White Tree and the Seven Stars.

What one also perceives more clearly with Johnstone’s manuscripts is the symmetry native to Tolkien’s writing, the rhyme and rhythm that was lost on some readers and critics when The Lord of the Rings first saw the light of day, as it rolled off the global printing press. Whether it is the archetypal mirroring — Jungian or not — between the loyal hound Huan and Sauron’s evil warg Draugluin in “Huan is there!,” or between the rambling tunnels of the Goblin mountain and the maze of caves in the Lonely Mountain in The Hobbit, there are many ways to look at the same thing. The flash of those facets is in many ways the power of myth as it works its way through our psyches.

Through them all is something like the serpentine wave, a dragon that winds through the darkness, on which by standing on the tips, one can look from one tip to another, and recognize time’s repeating cyclical nature. There is Bilbo, and yet there is Gollum, both hobbits from different times and fates, but interconnected nonetheless. There are the dwarves, and there are the goblins, both embittered enemies stretching back millennia, and yet, both live under the earth. There, Smaug writhes in red, and lusting for gold, and there, leads the motley band through the land — a wizard in grey and blue — shining the light, never threatening or breathing fire, or lording around his ancient might.

It’s the riddles and rhyming in Bilbo and Gollum’s encounter in the dark, and Bilbo’s test of wills and mind tricks in his conversation with Smaug, that remind us of the power of words. So it’s the same with Johnstone’s wordless manuscripts, which follow more in the tradition of stained glass windows of cathedrals, and tapestries like the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts William the Conqueror’s invasion of England in 1066. When we look closely at manuscripts like “The Killing of the Goblin King and the Finding of the One Ring” combined with “Conversation with Smaug,” we can see an interior symmetry and poetry.

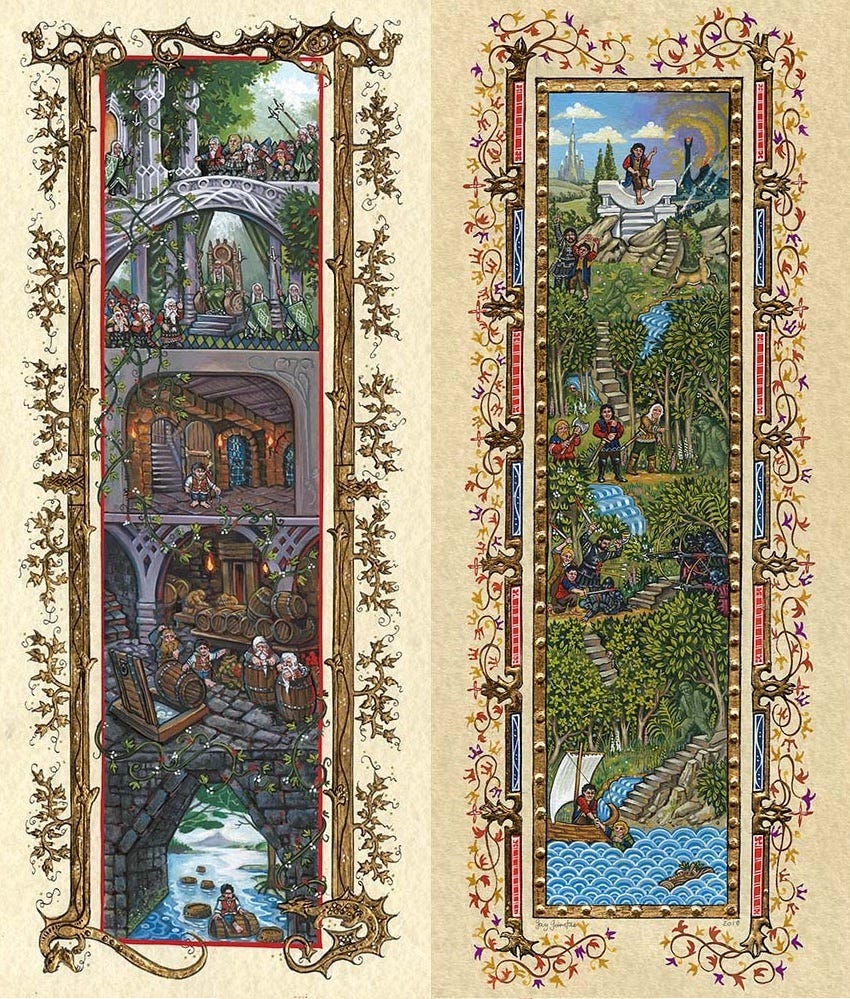

The first manuscript he painted of this kind depicts the end of The Fellowship of the Ring with Frodo’s indecision at the top of the hill known as Amon Hen. “It was a cross, because I saw it as a comic,” Johnstone explains. “And so with the ‘Flight from Amon Hen,’ which was the first one I did, it’s painted as this full story; from the moment with Boromir to the final bit where Sam jumps in the water and they steal away, it's almost like the story in cartoon form. It’s like a medieval comic. It was just a little dream thought. And it just worked.”

With these medieval tools at his fingertips, Johnstone has given us a wild peek at what a whole Red Book of Westmarch in manuscript form might actually look like; Not The Lord of the Rings per se, but the family heirloom of the Fairbairns, and monastic copies of it made in the scriptoriums of Minas Tirith.

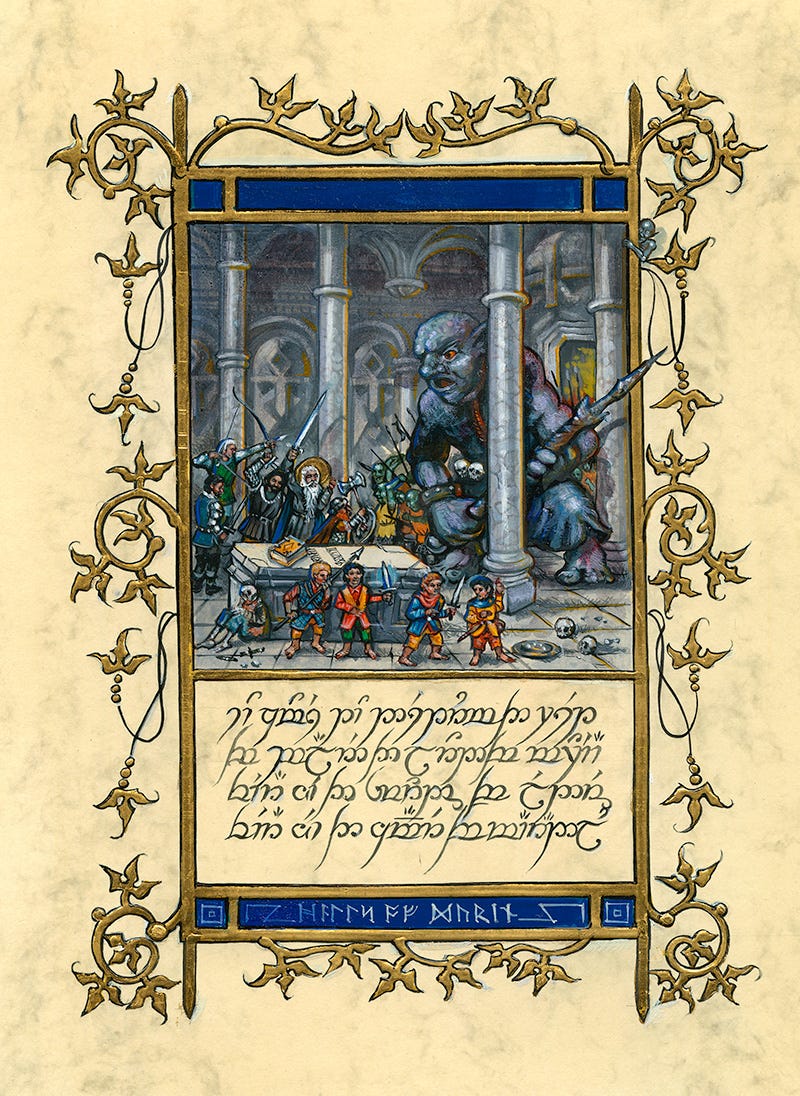

What would we see? Well, monsters for one. Just as Beowulf gives us three monsters in its epic tale — Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and a dragon — Johnstone more recently chose to illuminate the Fellowship’s journey through Moria with three scenes of three monsters: the Watcher in the Water, the cave troll at the Chamber of Mazarbul, and the Balrog at the Bridge of Khazad-dûm.

Which in a way brings Johnstone full circle. Its tentacles rising out of the water, his “Watcher at the Gate” depicts a classic scene from The Lord of the Rings in a new light, its curling limbs encircling the curvy Tengwar in the manuscript and evoking the tree tendrils around the columns of the Gate and the image. Even Pippin’s pipe-smoke curls with anticipation. But it’s all about Bill the Pony in a way, as he seems to be the only one who senses the giant mollusk of Moria, as Samwise prepares to set him free. Fittingly, Bill the Pony was also Johnstone’s gateway into Middle-earth.

“I was at art college,” he says. “And my girlfriend said to me, though, she was discussing with a friend, she says, ‘What was the name of that pony? What was the name of the pony where the Watcher was?’ And that was the question that got me into Tolkien. Because I was like, ‘What are you talking about!? What are you talking about? What are you babbling about?’ And she said, ‘Well have you read The Lord the Rings?’ I said, ‘What's that then? It's a book is it?’ I picked it up and that was me done from about page six. That was me done.”

Reading it on the bus to college everyday, and then rereading it, and going to secondhand bookstores to pick up The Hobbit, The Silmarillion and anything with the name “Tolkien” on it, Johnstone dove deep into Middle-earth. He understands the mythology with a painter’s hands and eyes, so that one recognizes the joy of every grace note and wink in his manuscripts.

In his second manuscript of his Moria triptych, “The Battle of the Chamber of Mazarbul,” you can see his secrets in Gandalf’s golden halo, as his angelic powers increase. A dwarf skeleton leans against Balin’s Tomb. Frodo’s Sting glows. And hiding on the right column behind the cave troll, is Gollum, trailing the One Ring. Looking on the bloodshed are the grim countenances of past dwarves carved in the walls, and two dwarf skulls trophied on the cave troll’s belt.

The third manuscript in the set is perhaps the strongest, because it brings something new to one of the most dazzling demons in modern literature: the Valarauka, the “power monster” in Quenya, the Balrog of Moria, Durin’s Bane. Here we see a devil in true medieval fashion with its goat-like head and curling horns: shaggy, fiery and baleful. Gandalf meets his sword and whip with his white light and what looks like a blueish flash, his gold halo more apparent, as the Maia goes against Maia — Maia a Maia — a stone dwarven face looking on from the column behind, while orcs aim their arrows at our heroes. It feels suitably Alighieri, a fierce confluence of words, symbols and archaic mystery.

And so a Balrog’s whip lashes out of the darkness. Tengwar springs from the same ancient well from deep down inside memory and legend, and the lost. It too remains both strange and familiar, reopening us to the metaphoric and malleable patterning of devils and angels. Like the illuminated manuscripts of the Bible, the stories and parables of The Lord of the Rings become a kind of mantra for survival, and a sermon for hope. Tolkien was a devout Roman Catholic and Johnstone is a devoted painter of Middle-earth. It takes a kind of religious fervor to bring these worlds to life, sparking our imaginations in the here and now.

We all take it for granted. Or at least the literate do. For many forget just how hard it is to truly learn our letters, buried in some distant childhood memories. Yet writing is a kind of miracle. The Jesuit priest Walter J. Ong reminded many scholars and scientists of this through his deep philosophical and linguistic analyses. His Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, which was published in 1982, argued how writing and reading marks a highly intense transition from a world of sound to a world of sight, and back again.

Ong also took intense interest in how the reading of symbols, letters and words could reshape human consciousness, describing how stories in written form can transport us out of conscious awareness of our bodies; as our immediate sense of place and time is muted, our internal voice and imagination moves to the fore of our experience. Johnstone’s manuscripts reminded me of Ong’s insights, which I once studied in college. For me, it’s in this context that Tolkien and Johnstone’s worlds collide to create a new kind of awareness: that Tolkien, by creating his own alphabets and languages, was essentially restoring an earlier state of wonder and erudition — a shared mythic dream state.

For myself, I never properly considered the core importance of Tolkien’s Tengwar and Cirth alphabets until observing Johnstone’s manuscripts. They weren’t just hobbies or handwritten doodles, though they certainly may have emerged from Tolkien’s constant play with language, but the elegant forms and calligraphy that articulate the deep linguistic soul at the heart of Tolkien’s faerie-expressionism. Tengwar, the alphabet for Quenya, the “Old Elvish,” or Latin language of his Middle-earth, seems both European, Middle Eastern and Asian all at once. Sanskrit comes to mind.** And yet it feels inherently Tolkien.

Which means it is both otherworldly and strangely familiar. Johnstone’s cursive and clipped styles of Tengwar also reveal its versatility, something all Tolkien readers, no matter their native language, recognize in the Tengwar script that flows around the One Ring, or along the arch of the Doors of Durin, or later explicated famously in Appendix E of The Lord of the Rings. No doubt, this creativity in lettering itself has driven certain rigid literary types mad.

“Why all the fuss!?” many may ask. Because within the handiwork of handwriting and the manuscripts of old was the hard work of caring for what was, what is, and what might be, even if only in the imagination. Knowledge is not free. Libraries may be public and commonplace for the most part today, and the information of the world hypothetically containable within digital code, simmering on servers and circuits and phones, but texts were once rare, and even sacred.

So I find Johnstone’s homage to this tradition not only clever, but touching. And if the movable metal type of Gutenberg’s printing machines literally transformed the medium of writing and reading into a galaxy of ideas, then Tolkien’s 20th century preoccupation with phantom letters is all the more ingenious. I don’t believe the impulse was anything more than creative, an impulse to dig back through the printed type on the page to the art of the hand, to reopen the mind.

It’s a kind of Houdini mind-body trick. Or a Marx Brothers steeplechase through one state of mind to another, from one gag to another, disdain or despair giving way to escape and laughter. It’s so easy to forget, but again, Tolkien wrote his masterpieces by hand, and then tested them out orally — like a magic spell.

One might say it’s almost like putting on the Ring. Because the trick is to make ourselves disappear, so that what remains are the words and our conjuring of what they mean, weaving through the passages of the manuscript like the worm or the wizard. It takes faith that these symbols can still connect to shared beliefs in fact or fiction, anchored to something deep in our memories, both personal and collective. Only then can it flow, from the pen or from the page.

In fact, Tolkien had delicate handwriting, the kind people rarely possess these days in a world of keyboards and touchscreens. In waves, his own manuscript picked up momentum as the rhythms of his legendarium overlaid, echoed and shimmered into a new mythic resonance. The words ran into each other as he quickened along, and then slackened as he took long respites on his writer’s journey, oftentimes sketching or painting scenes, images and scriptures that perhaps came loudest and clearest to his mind.

Every word along the way, he had to make some kind of decision. Most of it may have been semi-unconscious, especially once he found his stride. But some story and plot shifts took deeper consideration. Which is in its own way represented by the hero’s journey in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Once again, Johnstone’s manuscripts illuminate these profound patterns in new ways.

Putting “The Escape from the Dungeons of the Wood-elves” side by side next to “Flight from Amon Hen,” we can see how the two cousin journeys of Bilbo and Frodo echo but stray. In Bilbo’s manuscript, he is alone but lower in the totem pole. He is not the center of the action when Thorin defies Thranduil and is thrown into jail, though he is invisible and peeking from behind. He goes downward into the belly of the Wood-elves’ halls.

Leading the Dwarves to their escape, they get into their barrels and float off on the Forest River toward Esgaroth and the Lonely Mountain. Bilbo starts to come into his own. In a neat bit of alternating symmetry, intended or not, at the top of Frodo’s hill is Mount Doom in the distance, with the towers of Barad-dûr and Minas Tirith peeking into the clouds. On the Seat of Seeing atop Amon Hen, Frodo sits holding the One Ring, racked with indecision.

We can see events both before and after his deep view across the land: Boromir tries to take the Ring. Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli search for Frodo, who we can see as invisible hiding in the trees, with Gollum opposite and behind. We see Boromir blowing his Great Horn, pierced with three arrows, with Merry and Pippin beside him, Uruk-hai cocking their bows. And at the bottom, another decision at a river coming to a crescendo, as Frodo pulls Sam out of the water, setting sail for a new destiny across the Anduin, Gollum trailing on a log. So again, a Baggins starts to come into his own.

You never know where Tolkien may take you. His Red Book is a well-read manuscript, and yet every time is different. Johnstone’s Tolkien manuscripts show us just how far we still can go. Running through the worded and the wordless — new secrets revealed — one realizes that the possibilities for re-interpretation and reinvigoration are in fact infinite. How the letters relate to the image is a constant Ongian leap into the void and the timeless, only interrupted here and there by returns to the current.

Even reconsidering just one dimension of this puzzle, back to only letters, the dance of Tengwar is surprising and endless, in the same way that any language is, with new words and sentences promising something both deeply ancient and first of its kind. Speaking over Zoom, I ask Jay what he thinks about this elastic space between the visual look — Ong’s world of sight — and the meaning of Tengwar — the sound and poetry of Tolkien’s moral universe. To answer, he demonstrates the re-communion of myth, including its timing, by way of his own Tolkien parable of the artist — the transformation of an echo.

“I think it's beautiful,” he says. “I mean, I've seen some great scriptographers who can write it beautifully. I went to a science-fiction convention in Harrogate about three years ago and I noticed there was a lady in the corner actually painting in Tengwar script. And I just went over and she was using traditional Chinese brushes, and all this sort of stuff. And it was a beauty to watch.”

“When somebody gets it,” he continues, “it's poetry, just the hand motions. And I just stood for five minutes and didn’t say anything. I just stood watching there for five minutes. And then she stopped and she looked up, and she went, and I went, ‘Oooh, that's beautiful!’ And I said, ‘I’m Jay Johnstone. I’m a painter. I do some Tolkien stuff.’”

Jay leans in as he imitates her voice. “And she goes, ‘I know.’ She knew the entire time and didn’t look up,” he laughs. “She was wrecking it, because I was the ‘guy who did all the Tolkien script.’ It was a lovely little moment.”

Our consideration and conversation with Jay Johnstone will continue with our last and third part…

*Jay Johnstone is not the first Tolkien artist to work in this zone of the linguistic and the pictographic. For example, the artist Tom Loback, was one of the first to draw and ink elaborate Tolkien-themed manuscripts in Tengwar and Cirth. Interestingly, some of his artworks have a Hindu / Sanskrit, or Devanagari influence in its script stylings and visual flare.

**Connections to Sanskrit have been made more explicitly in recent Tolkien scholarship. Mark T. Hooker’s Tolkien and Sanskrit: The Silmarillion in the Cradle of Proto-Indo-European, takes a fascinating look at the role of this ancient language in Tolkien’s academic and linguistic development. It’s highly speculative but still a very fun read.