The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder

Part Two: The pantheon of Arda and the shaping of the World

Last time we delved into the deeper thematics of J.R.R. Tolkien’s early writings about the Valar — his “Gods,” known also as the “Powers” — and how their first real travails within the confines of the World sets in motion Tolkien’s moral and aesthetic philosophy of spiritual change. This “story,” shifting from one of music to one of light, animates all of his mythological designs. Our “Part Two” takes a look at some of the other details in the same chapter from The History of Middle-Earth (THOME), which concerns “The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor.” What we find is a more neutral but vivid tone than what survived into The Silmarillion. It is more pagan and Classical i.e. Roman. As a result, it feels more familiar and at times bizarre. And, it explores life after death.

[Catch up with our first posts on THOME, diving into chapters one, two and three.]

The chapter begins with the elves Rúmil and Lindo continuing their recounting of the early history of the World to the wandering human mariner, Eriol. While the main force of The Book of Lost Tales narrative has clearly shifted by chapter three to the actual drama inside the “lost tales,” it is important to remember that the meta-narrative of this “story within a story” is still the literary device Tolkien is using to give the proceedings a greater sense of believability. We took care to point out the intelligence of this strategy in our first post on THOME, which celebrated the dream-like quality of The Cottage of Lost Play.

Taking another step back, what is fascinating about this ongoing method in The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor, is that while The Cottage of Lost Play centers on Eriol’s prehistoric arrival to a magical island — in fact, England — we look back with growing clarity to an even older history that begins to take on its own forward momentum. Our second post on THOME looked at The Music of the Ainur, which unfolds once, twice, thrice and arguably infinite times through the metaphor of music, as an expression of God’s consciousness and medium of his imagination, with polytheistic emanations in the form of angels, i.e. the Ainur, and hence the Valar.

We are told in a number of ways that this Music will ripple throughout time, and continue to unfold in surprising ways made possible by the counter-actions of a selfish angel named Melko (i.e. Melkor), and then the counter-reactions made by others, including God (i.e. Eru Ilúvatar), to fix those hurts, hence bringing forth even more beauty beyond the original themes. So once we get to the Valar entering Creation, we then shift to them embodying that Creativity.

Yet before we go into that deeper fantastical rhythm, Tolkien has Rúmil, Lindo and Eriol once again frame this drama with a sense of distance, that ironically, by design, makes it more intimate. I think what Tolkien is doing here, is riffing on the contradiction at the heart of Creation itself. When writing about his God and Gods, he was careful to layer in more erudite and vicarious modes of narrative, something that gives the experience of first-person without actually writing in first-person. It’s a kind of magic trick, like gold sifted out of mud.

To wit, there is I believe a continual sense that one is looking through water and surface into a deeper register of existence when reading The Book of Lost Tales, an effect that Tolkien would refine and repeat through all of his fiction, bridging the present, and the future, with the past, bridging fantasy with reality. It’s not unlike when Frodo and Sam look into Galadriel’s Mirror, “things that were, things that are, and some things that have not yet come to pass.” This hydromancy, or water scrying, is not a bad way to think about Tolkien’s mythology. For it is a bewildering then incredibly articulate vision of our own world.

So while our third post on THOME looked at the bottom of that mirror in the context of the Valar, here we are looking at some of the disturbances on the water surface. Those ripples and flashes of light at the rim and around the center are not throwaway, though as you will learn (if you have not read THOME), Tolkien did indeed remove much of it as the water settled in his mind. By The Silmarillion, Eriol would be gone. Lindo too. And Rúmil reduced to just a sentence or two.

This was not intentional on my part, but we ended the last post, our “Part One” on The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor with its central image, the Two Trees, one gold and one silver. They are symbols dear to Tolkien’s heart, the fount of much of his grand miraculous mythology. It’s as if they grew from the bottom of his water basin, from his own mirror, branching out and unfurling leaves and bearing fruit, and glimmering with the light of Creation.

That light first shines in against the contrast of darkness with the morning sun. Picking up right where Rúmil’s retelling of The Music of the Ainur left off long into the night, Eriol shows himself a devoted audience. “Great are these tidings and very new and strange in my ears,” he says to Rúmil, “yet doth it seem that most whereof you have yet told happened outside this world, whereas if I know now wherefrom comes its life and motion and the ultimate devising of its history, I would still hear many things of the earliest deeds within its borders…”

And so the “life and motion” of Tolkien’s devising of an alternate history laps over cosmic borders into a primordial Earth, a tabla rasa of mythic fantasy that moves from the Music to Matter. For with the “Coming of the Valar,” his vision flows into one of physical things animated by the laws of Nature and supernatural consciousness in the form of angels shaping the World.

It is here, that The Book of Lost Tales starts to move into the territory of physical experience, though it is still rife with the spiritual. Indeed, Tolkien’s message as we move forward is that they are one and the same, and he readies us for this swelling of the waves of history by having Eriol ask for much more than the cosmogonic creation of the universe, but of its drama in human form:

“of the labors of the Valar I would know, and the great beings of most ancient days. Whereof, tell me, are the Sun or the Moon or the Stars, and how came their courses or their stations? Nay more — whence are the continents of the earth, the Outer Lands, the great seas, and the Magic Isles? Even of the Eldar and their arising and of the coming of Men I would listen to your tales of wisdom and wonder.”

Wisdom and wonder! Tolkien wrote these words sometime between 1918 and 1920, after the First World War. The Spanish Flu raged during these same years (ahem, a global pandemic?). Communism was spreading following Red October in 1917, sweeping through Russia. The Nazi Party was formed in Germany and just a few years later Adolf Hitler wrote his deranged manifesto Mein Kampf in prison. American writers Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, innovating a more direct and terse style of writing, ascended. Tolkien’s archaic head-trip was out of step with all of these modernist pretensions and eruptions.

And yet, as tentative as some of the steps he made here in The Book of Lost Tales, — which to my eyes bears the choices of a more novice hand — these steps lead nevertheless to The Silmarillion, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, books that have secured their place in history as “tales of wisdom and wonder.”

How did he get there? Well, the simple answer was the courage to go his own way, to be weird, to dream bigger than anyone so far. It is of course very interesting to point out, in my mind, how Walt Disney was Tolkien’s contemporary. He was nine years his junior and died seven years before Tolkien, but like the British scholar, the great American fantasist came from little, and where others saw occupations fit for children, Disney imagined an entire universe, beginning with a mouse, and ending with the most immersive and enchanting theme parks the world has ever known and probably ever will.

Tolkien’s tone and touch is utterly different, however. Both made an art of wonder. But while Disney certainly made wisdom a core aspect of his tales, drawing many from age-old myths like the Brothers Grimm’s source of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Sleeping Beauty, he made whimsy its equal. Tolkien had his share of whimsy, for sure, especially with his hobbits, but wisdom was more his ken.

I think where we find this as early as The Book of Lost Tales. Besides Eru Ilúvatar’s cosmic symphony, the first distillation of wisdom and wonder in The Book of Lost Tales is the Two Trees: Laurelin and Silpion. Once again, Tolkien is approximating his own kind of Tao, perhaps an intuitive outcrop of his tragic childhood, losing one parent and then the other by the tender age of 12. Disney had a rough start, one plagued by his father’s overwhelming sense of failure. But he was never an orphan, a fate — the worst fate, for any child, other than death.

For Tolkien, it was a death, the closest one could come. It’s in part why, it seems to me, that he would describe leaving his wife — his sweetheart and fellow orphan that he met in a boarding house — soon after they married for the Battle of the Somme with a high degree of fatalism: “Junior officers were being killed off, a dozen a minute. Parting from my wife then ... it was like a death.”

John Garth also recounts, in his booklet Tolkien at Exeter College: How an Oxford undergraduate created Middle-earth, that Tolkien was either obsessed or fascinated by ghosts, in the broadest senses of the word. In 1912, his second year at Oxford, he won a debate by a single vote on his closing motion “That a belief in ghosts is essential to the welfare of a people.” That is, contemplating the connection of past lives to current lives and to an unknown future, for Tolkien, was essential not just for historical wisdom, but for a sense of wonder at the nature of time and our place within its mysterious echoes.

Put another way, as Barth argues, “the link between the supernatural and the ‘welfare of a people’ foreshadows Tolkien’s interest in myth as a cornerstone of a nation’s selfhood — which would lead him to develop what he thought of as a mythology for England.” Like Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors and polka-dotted artwork, inspired by the sun and moon, Tolkien perceived “ghosts” as deeper undercurrents in the life of a people, of his people, and eventually, all people.

Consciously or not, his mirror was a kind of time machine. While we all first read Tolkien’s tale of the Two Trees of Valinor as a primarily organic affair, fixated on the imagery of tree branches and drooping fruits in a spring eternal, the stillness that comes over us when we imbibe such inspired imagery reflects our own less liquid state of human matter. It is the infinite repetition that artists like Kusama have also perceived in Nature, whether we’re talking Narcissus mirror globes, polka dots, fractals, ripples, memories, lives or ghosts. What in us endures?

Like Tolkien and Disney, Kusama also had a traumatic childhood. Her mother often destroyed Kusama’s artwork, her natural instinct to create attacked. Her father was a philanderer; her mother would force her to spy on her father while he was having sex with other women. Hallucinating bursts of polka dots at an early age, she would take that motif and explode it in a dizzying array of paintings, sculptures and even performance art. A sufferer of mental illness, her art is a courageous act of constant self-healing and reception of the divine.

I am comparing Tolkien with Kusama and Disney for more than artistic or thematic reasons, but because all three are giants of 20th century art, and very importantly, when looking at them together, represent waves in a greater sea. Those waves crested in Europe, America and Asia, and calls to mind the global span of the Valar’s labors at the beginning of Tolkien’s grand design. All three of these artists are very different who lived incredibly different lives, coming from vastly different traditions, working in different mediums, mastering their own unique voices, and yet they are connected by this larger tide of time.

Some call this timelessness, the ability to access and express the eternal. But I think we can also look at timelessness as representing a kind of mirror of the self recognizing its temporal reflection in the universal. That is to say, that it is what we all see as unique in ourselves is not necessarily mortal, but a ghost wave that runs backward and forward without end. I think that is why Tolkien’s mythology resonates around the world, like Disney’s empire of entertainment and Kusama’s cosmic nature.

I was reading about Kusama’s “Cosmic Nature” exhibit in The New York Times as I was pondering Tolkien’s Two Trees, holy organisms that pulse and shine with the light of Creation. And it seemed like once again, here were patterns deeper than all of us, that Tolkien and Kusama did not create, but simply discovered, and brought out of darkness. So that we get Tolkien’s literature as a kind of world medium, one where words work like the surface of water, obscuring and then revealing the deeps of time. It is mythology as hydromancy.

So we look down on the page just as Tolkien’s god Lórien, Lord of Dreams, looks into the deep pools that nourish Laurelin — “tree of flame” — and Silpion — the White Tree — and across their surfaces, where he scries mystic visions. There we see two goddesses at the center of this drama, their names Yavanna Palúrien and Vána Tuivána, who raise these two cosmic trees from two vats of liquid light, one golden and one silver, named Kulullin and Silindrin. In them, is the vibration and divine mystery of Creation, going back to the birth of the universe.

At Laurelin’s bloom and then Silpion’s, Tolkien wrote of the Valar, “Then did the Gods praise Vána and Palúrien and rejoice in the light, saying to them: ‘Lo, this is a very fair tree indeed, and must have a name unto itself,’ and Kémi said: ‘Let it be called Laurelin, for the brightness of its blossom and the music if its dew’… Lórien could not contain his joy, and even Mandos smiled. But Lórien said: ‘Lo! I will give this tree a name and call it Silpion,’ and that has ever been its name since.”

Like Kusama’s rippling patterns, Tolkien riffs on the rhythms of nature. He takes silver as a substance, a luminous quality, and a word, and spins it into a dazzling wave of gentle sibilance: Silver, Silpion, Silmo, Silmaril, Silmarillion. Silmo is here the name of Lórien’s angel who waters the White Tree with the silver waters of Silindrin. The Silmaril is a gem that captures the light of the Two Trees.

“Glowworms crept about their borders and Varda had set stars within their depths for the pleasure of Lórien, but his sprites sang wonderfully in these gardens and the scent of nightflowers and the songs of sleepy nightingales filled them with great loveliness,” Tolkien writes of Lórien’s house called Murmuran, with its gardens full of labyrinths and mazes; was he playing on the “murmurs” of divination?

“Lórien gazing upon it saw many visions of mystery pass across its face,” he writes of Silindrin, a cosmic lake of epic repercussions, the first source of the White Tree that would propagate Kusama-like in multiple forms over time, emerging as one of Tolkien’s most enduring symbols of life’s preciousness: “and that he suffered never to be stirred from its sleep save when Silmo came noiselessly with a silver urn to draw a draught of its shimmering cools, and fared softly thence to water the roots of Silpion ere the tree of gold grew hot.”

In The Silmarillion, not much is written about Lórien — who is also named Olofántur in The Book of Lost Tales. He is the brother of Mandos, who is the Doomsman of the Valar and keeps the dead in his vast halls. We are told later that “Lórien” is also the name of the place, filled with trees and lakes where the Valar and Eldar come to rest and dream. The name Murmuran does not survive into The Silmarillion. For Tolkien fans, Lórien is both the root and inspiration of the name Lothlórien and its dreamy quality in The Lord of the Rings. Importantly, Olórin is a disciple of Lórien and his sister Nienna, who teaches him pity and patience. He is an angel and the wisest of the Maiar —Tolkien’s name for gods of lesser power than the Valar. He is Gandalf.

As in the Valaquenta in The Silmarillion, the successor to The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor in The Book of Lost Tales, much energy is given to the description of the Valar, their attributes and their domains. Like many polytheistic and pagan mythologies, these gods represent different aspects of nature and human nature. This is the “familiar” quality of his pantheon.

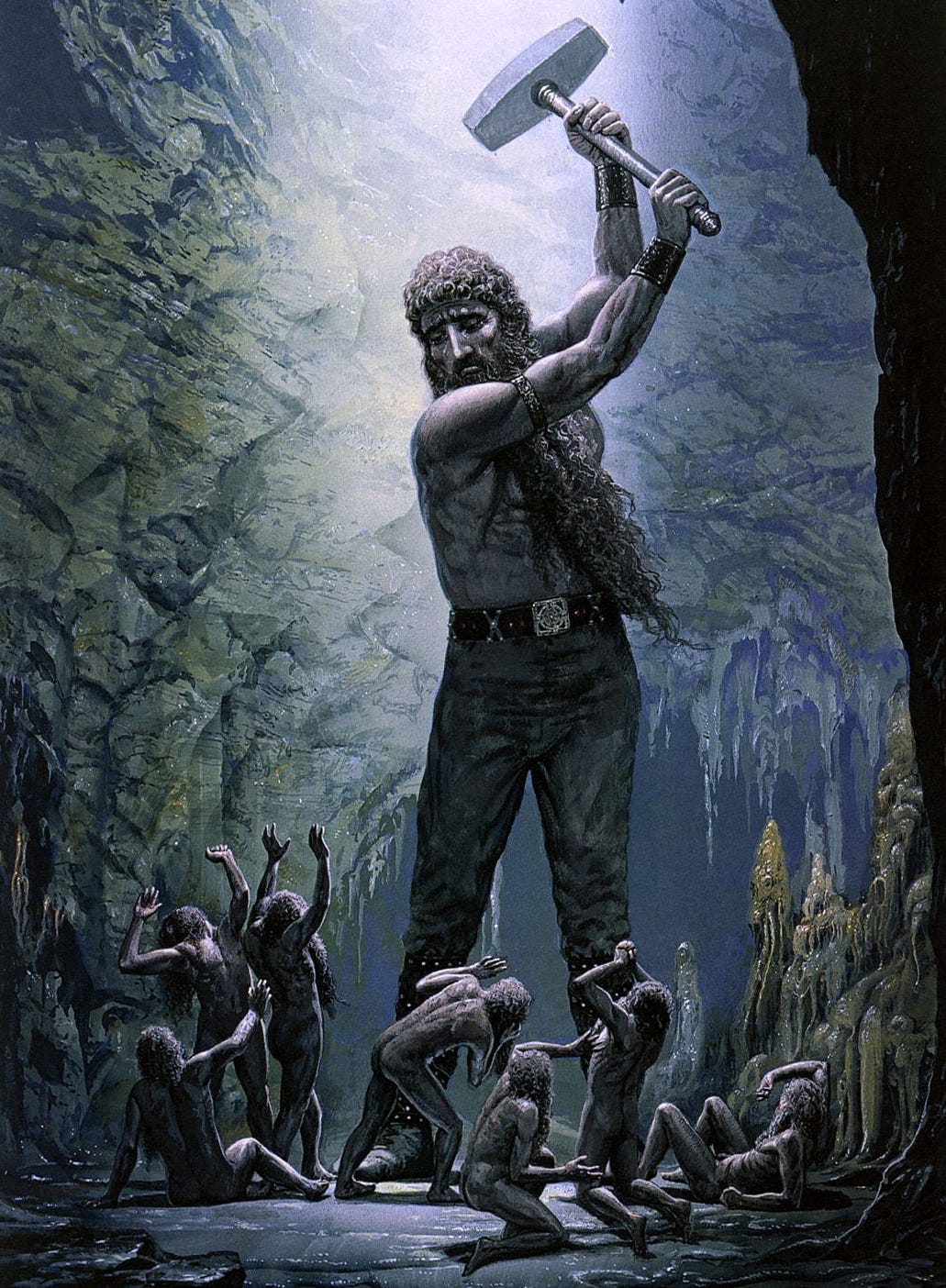

More familiar are certain members of Tolkien’s family of gods, like Tulkas, who shares much in common with Thor from the Norse pantheon. Indeed, the Two Trees owe a lot to Yggdrasil, the sacred tree at the heart of Norse cosmology.* And Odin shares much in common with Gandalf, and perhaps Lórien. Interestingly, Tolkien goes straight from his descriptions of Lórien and his realm to Tulkas.

“Otherwise was the mind of Tulkas,” he writes, who revels in deeds of physical daring, not dreams. He is fearless and laughs in the face of danger. He wrestles and runs and leaps, and delights in “songs that go with a swing and a toss of a well-filled cup.” His abode in Valmar, the city of the gods, where his “tower of bronze and pillars of copper in a wide arcade” house mirth and drinking. Here Tulkas takes on the gregarious air of a viking king much more so than in The Silmarillion, drawing a closer vibration of the Valar, Valmar and Valinor with Valhalla, Odin’s hall of the fallen brave in Asgard, tended by the valkyries.

Tolkien’s moral and aesthetic philosophy of spiritual change, still in its earliest forms in The Book of Lost Tales, is both confident and not yet fully distilled. We get a vision of Valmar that is more mead and wine toned than the more elevated and original vision of the Gods we will get later in The Silmarillion. We have Salmar — you can sense the sonic and linguistic rhythms rippling in Tolkien’s imagination from Valmar to Salmar — who survives in the later text, but is here given a more Classical rendering, an angel “raising sweet music with an instrument of the bow.” Violins did not appear in Europe until the Roman lyra in the 9th century, by way of the Byzantine Empire.

Here we also get Amillo, also known as Ómar, Salmar’s brother, who were are told has greatest singing voice. And there is Nielíqui, the “little maiden” who danced about the woods. Along with the image of Salmar playing his music under the tree Laurelin — which calls to mind Pan and his flute — the images of Amillo and Nielíqui have a more Roman and ancient Greek sensibility to my mind.

As further indication of how these affect tone, Salmar is kept only to the sea in The Silmarillion — one of Ulmo’s tribe — and instead makes the horns of seashell known as the Ulumúri, telling us that Tolkien perhaps later winced at the overly Classical allusions, and instead was in search of something more timeless. Seashells go far back into nature time immemorial. Violins do not.

Some of these details give parts of this chapter a “bizarre” tenor, in that you can sense that The Silmarillion is a more fully realized vision than it has sometimes been cast. Tolkien did not perfect it to his satisfaction before he died, but The Silmarillion’s more spare telling of the Valar belies a minimalism that greatly benefits its final form — perhaps “less is more” when it comes to Gods.

He would find other ways to “children” his mythology into the eternal. While he played with concepts like the Valar having children themselves, in the end he wisely cut back on some of the anthropomorphism one sees in most other mythologies, making them more believable as spiritual metaphors for the mysteries of matter and the natural features of the Earth.

For example, in The Book of Lost Tales, Palúrien is Oromë’s mother. And we’re told that in Oromë’s “vast domain” of forests and grasslands, that “bison there were, and horses roaming unharnessed.” He removed the “bison” reference later, perhaps because it was too strongly associated with American buffalo.

Tolkien’s descriptions of the Valar’s lodgings also receded later, again, for the best. While it is interesting to read some of these earlier imaginings, with the exception of Lórien, most of them seem to subtract from the believability of Tolkien’s sub-creation. In Oromë’s case, like Tulkas, we’re given images that hew closer to human needs, here a hunter’s lodge with skins, furs, trophies, and antlers.

We’re also told that Fui (Nienna), sister of Mandos, has a dark hall with a roof of bats’ wings. This again, ties more to popular images of witches than it does to the more purely spiritual poetry Tolkien achieves in his later vision of the Valar in the Valaquenta. Even so, the bones of Tolkien’s style are here, dark beneath the waters. “Slaughter and fires, hungers and mishaps, diseases and blows dealt in the dark, cruelty and bitter cold and anguish and their own folly bring them here,” he writes, “and Fui reads their hearts.”

And there is beauty here too that is by necessity “lost” in The Silmarillion, that when reading feels like one is there right with Tolkien, standing just behind him and looking over his shoulder into wonders that seem like they’ve come to us from some ancient dream of the world as it was once seen. Reminiscent of the Greek psychopomp Charon, the ferryman who takes the dead across the river Styx into the underworld of Hades, Tolkien describes the black ship of Mornië that sails from the halls of Fui:

“Then do all aboard as they come South cast looks of utter longing and regret to that low place amid the hills where Valinor may just be glimpsed upon the far off plain; and that opening is nigh Taniquetil where is the strand of Eldamar. No more do they ever see of that bright place, but borne away dwell after on the wide plains of Arvalin. There do they wander in the dusk, camping as they may, yet are they not utterly without song, and they can see the stars, and wait in patience till the Great End come.”

Some of the dead, the wicked, she sends even to Melkor, and his Hells of Iron, named Angamandi — later varied to Angamando and Angband. There are other notions and names besides that would change, sometimes a lot, sometimes a little. Vairë, a name in The Book of Lost Tales that originally belonged to one of the elves that host Eriol, later becomes the name of Mandos’ wife. He is also called Vefántur — a variation on Fántur, the shared name for him and his brother Lórien, later to become Fëanturi, the “spirit masters” — and he calls his “sable hall” with caverns stretching down under the Shadowy Seas, simply Vê. Perhaps by design, Fántur evokes words like “phantasm,” “phantom” and “fantasy.” Hence, marking the seriousness of Tolkien’s mythology, we can draw a line from “fantasy” to “spirituality,” a word that goes beyond dream to questions of mortality.

You can see other traces of this evolution of thinking from 1920s contemporary “fantasy” into the more focused world-building of Tolkien’s masterpieces. Sprites, pixies, brownies, fays and leprawns are mentioned as sentient beings that followed Aulë and Yavanna Palúrien into the World. He also lists related categories: Tavari, Nermir, Nandini, Orossi, Oarni, Falmírini and Wingildi. The latter three are sea spirits that call to mind kelpies, selkies and mermaids. Importantly, at this time, Tolkien did not have a conception of the Maiar, his later class of angelic beings less powerful than the Valar. In The Book of Lost Tales, all “angels” are Valar. It reads as a result a bit more like watching Disney’s Fantasia than Tolkien.

We also hear a considerable amount about the Valar named Makar and Meássë. They do not survive to The Silmarillion. Christopher Tolkien in the endnotes of the chapter refers to them as a “Melko-faction” in Valinor that “was bound to prove an embarrassment.” From what I can tell, they read more like pagan gods who are amoral and represent instead the fires of civilization, in this case war. So like Ares, the ancient Greek god of war who was later called Mars by the Romans, Makar is more like an alien force that represents an inherit belligerence within the human psyche. His sister Meássë is the same — essentially a troublemaker.

“But that house was full of weapons of battle in great array,” Tolkien writes of their domain, “and shields of great size and brightness of polish were on the walls. It was lit with torches, and fierce songs of victory, of sack and harrying, were there sung, and the torches’ red light was reflected in the blades of naked swords.”

The removal of Makar and Meássë from The Silmarillion saves it from a moral incongruity that would have muddied the waters of Tolkien’s mythology. In fact, while many critics have wrongly accused Tolkien of being too “black and white” about his treatment of good and evil in the universe, by instead moving violence and “red light” — blood and fire — to the domain of Morgoth (Melko’s later name) and Sauron, he accentuated the choice and the contrast, giving greater dramatic force and ultimately reality to his morality tales. For these forces are always at war within us, unless we seek balance. The idea of Makar and Meássë as givens in his pantheon of gods would be a dereliction of sorts, an acceptance of an old cynical grey that only clouds the questions he asks our complex post-modern age.

Not to be missed, is a poem tucked in the last endnote of the chapter, titled Habbanan beneath the Stars. Christopher Tolkien tells us that according to his father’s letters, it was written during the First World War either in Brocton Camp, Staffordshire in December 1915, before he was mobilized to France, or in Étaples in June 1916, just weeks before he would march into the Battle of the Somme, the deadliest battle in British military history. While his son focuses more on the connection of the poem to the Mornië passage above, it also evokes Makar:

“In Habbanan beneath the skies / … For there men gather into rings / Round their red fires while one voice sings / And all about is night.”

“Habbanan,” Christopher Tolkien shows us in the chapter’s copious endnotes, revealing a background with many corners and strange paths, was associated later with “nigh Valinor,” and therefore approximates other regions in immortal Aman, the later name for the continent that contains Valinor, and Eruman, and before that, Habbanan. But the “red fires” also call to mind the “red light” in Makar’s house. It is a beautiful and rather melancholy little poem. From it, one sees how death was on Tolkien’s mind. Here he draws images of an afterlife. He writes in a brief introduction to the poem: “Now Habbanan is that region where one draws nigh to the places that are not of Men.” That is, the land of the dead.

[You can read the full poem of “Habbanan beneath the Stars” here. It is short and sweet.]

Gods and phantoms, angels “alive” before the World comes to be, the slain on the “wide plains of Arvalin,” or Habbanan — for Tolkien, all are ghosts “essential to the welfare of a people.” For his poem seems to evoke the encampments Tolkien stayed in his training for war and in his “utter longing” for home from Étaples, crossing his own river Styx into the killing fields of the Somme.

Here we find Tolkien’s wisdom and wonder like an early fire spark in the darkest night of the soul. Incredible violence laid before him that would take the lives of two of his best friends. They had encouraged his poetry, and here it is in a very bright and clear form, beneath the Stars. It’s almost a kind of Ring Poem for Tolkien’s Silmarillion, a gem buried here in the deeps of the sea or set in the firmament, just like the Silmarils of his vast mythology.

Much of this would be lost if it weren’t for the great work of his son. Three chapters in, I think it is worth noting just how important Christopher Tolkien’s contributions are to world literature. Without The Book of Lost Tales or the gems he uncovers in THOME, our ability to see deeper into the mysteries of the human imagination would be greatly diminished. Whether it is the prophetic power of Habbanan beneath the Stars, a scrying as much about Tolkien’s own journey into death as it is about the dead looking back to Valinor, or the rich jumbled soil of Valar names, their powers and their mansions, what we get here is closer still to the question Christopher must have asked himself as he too looked through the sometimes confusing waters of his father’s manuscripts.

Why? Why did his father’s parents die? Why did he long so much for his mother? Why in the Battle of the Somme did young men have to fight and die? Why do we feel the pull of our ancestors and the call of the future into unknown destinies at the same time? Why does one even write or make art? In The Coming of the Valar and the Building of Valinor, Tolkien was just starting to ask these questions more pointedly through his mythology.

He would answer some of them much later. Aulë, the Vala who has most substances under his rule, and who helps shape most of the mountains and lands of Valinor and Middle-earth, creates the dwarves. The Seven Fathers of the Dwarves, including Durin, are his attempt to create sentient living beings. Spiritual embodiment however remains the domain of Eru Ilúvatar. Aulë’s creation of the dwarves is forbidden, but is forgiven, because he defers.

There is also the evil spirit Ungoliant, a spider witch who even Morgoth fears. Her story is yet to come in The Book of Lost Tales, as are Morgoth’s many machinations and deceptions. Like Aulë’s dwarves, the rendering of Ungoliant in The Silmarillion is a more deliberate movement. Her domain is darkness itself, what Tolkien later would call Unlight. Different from Makar or Meássë, she represents a contrast as great as Kusama’s black polka dots on yellow.

This reinforces the hierarchy of Tolkien’s monotheism synthesized with his love of polytheism. The great wars with Morgoth to come, are about domination, not domain. Which bring us back to the “Fay,” or Faerie. In fact, in this chapter, we hear of the “Bay of Faëry” early in its pages. It seems to be in close proximity or part of Eldamar, which is west of the island Tol Eressëa, where Eriol is hearing all of these tales from Rúmil. From Taniquetil, the highest mountain in the world and where Manwë and Varda — the king and queen of the Valar — reside in Valinor, they look out over the sparkling waters of the Bay toward Middle-earth.

It is there again that Tolkien returns us as we step away from his mirror. Coming back to the “present,” the narrative reminds us that we are in a multi-layered meta fiction by making it more familiar, this time in the form of elven children asking for more magical yarns of yore, their language highly medieval in mode:

“another child spoke from a cushion nigh Lindo’s chair and said: ‘Nay, ‘tis in the halls of Makar I would fain be, and get perchance a sword or knife to wear; yet in Valmar methinks ‘twould be good to be a guest of Oromë,’ and Lindo laughing said: ‘ ‘Twould be good indeed,’ and thereat he arose, and the tale-telling was over for the night.”

And yet, this familiar scene that any adult and child can recognize, is utterly strange, transformed now back to what it is. Not just dead words. But time travel of the mind, and indeed the spirit. For here in his Book, Tolkien recovered the ghost that lies between. The more you look, the more it reflects.

Life, Reality and Illusion are great forces at play in Arda and in Tolkien’s metaphysical drama. With his “explorations” here of Valinor and the Valar, he constructed a kind of magic mirror. Next time, we will step through it with him.

*While Yggdrasil is an obvious precedent to Tolkien’s Two Trees, he actually denied it as a big influence on his mythic conception of Laurelin and Telperion. He in fact told an interviewer once that they were more inspired by two cypress trees of Zoroastrian legend, the Trees of Sun and Moon, which are accounted in the tales of Alexander the Great, in particular a Middle English poem that Tolkien knew well, Kyng Alisaunder.

Our History of Middle Earth Journal Index - The Book of Lost Tales, Part One:

The Cottage of Lost Play / Opening the Heart of Modern Myth

The Music of the Ainur / Tolkien’s Creation and the Creator

The Coming of the Valar / The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder, Part One

The Building of Valinor / The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder, Part Two

The Chaining of Melko / Who the Hell is Tinfang Warble?

The Chaining of Melko / The Convolution of Evil in Middle-earth

The Coming of the Elves / Tolkien’s Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems, Part One

The Making of Kôr / Tolkien’s Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems, Part Two