Tolkien's Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems

Part One: How the convolutions of Ossë shaped the purpose of the Elves

Following The Chaining of Melko, the fourth chapter of The Book of Lost Tales: Part One, of the monumental History of Middle-Earth (THOME), we move into the fifth chapter, The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr. Like the last chapter, it is an odd one, a mixture of unsure storytelling and moments of mythological brilliance. In the same way that the fay character Tinfang Warble conflicted with the darker descriptions of Melkor’s hellish redoubt, this chapter retains some of the more twee tones of stereotypical “fairy tales” while belying the weirder and stranger imaginings of J.R.R. Tolkien.* Like a steady but unmistakable tide, his deeply eccentric aesthetic — for that is what it is, though we take it for granted — emerges in moody imagery and inspired passages of description.

But to get there, we first have to surmount sea barriers that resist his powers. Like the previous waves, it begins with the human mariner Eriol and an elfin storyteller who recounts a “lost” history to him about the origins of the world. Queen Meril-i-Turinqui tells of how Melko was imprisoned and how the Valar — Varda especially — prepared for the coming of the Eldar.**

The text for some time carries an antiquated vernacular, with “methinks” and “thither” and “stonied” and “blindeth.” It’s not so much that these archaic words are bad in and of themselves. Clearly Tolkien was taking a cue from the writers of his youth, including 18th century interpretations of Norse and Celtic mythology. This was the “lingo” so-to-speak of legends and tales and it seems to me that it took Tolkien a while to find the right tinge of this quality.

It also seems this is true of his own names, many here being of weaker quality than the names he polished and settled on later. So that you have “Solosimpi” and “Tinwë Linto,” “Nornorë” and “Silubrilthin.” These are not terrible constructions. But they lack the sharp balance he later achieved, so that “Solosimpi” later became the “Falmari” and “Tinwë Lintö” became “Thingol.”

I know it’s “subjective,” but my strong opinion is that Tolkien greatly improved the narrative of the coming of the Elves and his names over time. The first half of The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr is pretty rough going. It is confusing and uneven in tone. I’ve noted the archaic language as one distraction. The other however is the Valar and the Maiar, who are rendered here as “all too human.” That is, very much in the mold of ancient Greek drama and plays, as well as Homeric legends (though Homer balances this out some in the Iliad and the Odyssey), we get gods who bicker and exuberate.

The first example of this is when the Valar realize that the Elves, the first Children of Ilúvatar, have awakened in the world — in this rather abrupt scene, Oromë, god of hunting, emerges in Valmar to declare their arrival: “Tulielto! Tulielto! They have come — they have come!” It is also stated just before, that the goddess Varda had also made many stars to commemorate the coming of the Eldar, but that in fact it was the blacksmith god Aulë who sparked them from his forge. Did Varda create them or did Aulë? It’s unclear. Tolkien seems pulled in two different directions over a matter that seems superfluous to the dramatic origin story of one his greatest creations — the Elves.***

That’s in part why the “Tulielto!” bit from Oromë feels melodramatic. Manwë senses that the Elves have awakened. Varda rushes to make stars to celebrate, then rushes back and drops a bright star named “Morwinyon,” but we’re told Aulë actually created the Seven Stars, and then Oromë shows up. It’s a lot of information and gives the impression that the Valar are clumsy.

That’s not to say that gods or nature or the universe is orderly. The previous chapters have spent many breaths establishing that chaos — and in particular Melkor and the impulse to control Creation by subjugating or destroying — is inherent to the cosmos.

However, while many have long criticized The Silmarillion — the evolved and “final” articulation of the tales first devised in The Book of Lost Tales — for being heavy on linguistic inventions but light on actual storytelling, it seems to me that its sparseness is part of its power. “Tulielto!” is not as effective as Tolkien’s much simpler descriptions in The Silmarillion of the coming of the Elves. For example, his detailed description of the lake that the Elves first awake next to, far east in Middle-earth, called Koivië-néni here and Cuiviénen in The Silmarillion, evokes something more poetic and starker in the later version. Where here the speedy Nornorë — a kind of Hermes or Mercury — runs in a flash from Valinor to Cuiviénen, and there talks to them in high speech, whereas later in The Silmarillion, no speech is relayed. Instead, we get a mythic quiet.

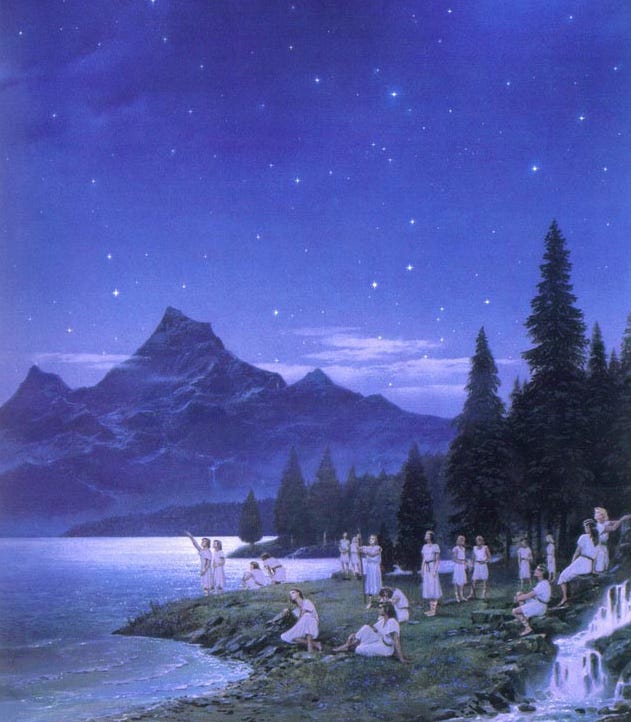

In fact, much is different in The Silmarillion. For one, Tolkien describes Oromë’s discovery of the Elves, which is written with great beauty and economy. We learn that the Elves awaken as Varda completes her work kindling many great stars and constellations in the dark sky. There is no mention of Aulë co-creating the Seven Stars. All praise is given to Varda, and it is the stars that the Elves first see, and from thereon hold her in the highest regard among the Valar.

We also learn that they hear running water and become enchanted by its music in The Silmarillion. They also make speech, and hence call themselves the Quendi — “speakers” — and are harried, we learn, by Melkor. It is this preying on the young Eldar that prompts the Valar to besiege Melkor and chain him. Only then do we return to the question of whether, and how, to bring the Eldar to the land of the gods. There is a great debate in The Silmarillion, and the decision to remove the Eldar from the threat of Melkor is given great consequence, memorialized by Mandos, the Doomsman of the Valar: “So it is doomed.”

Gulp! There is in fact very little of this fateful twisting and turning in the original work. That Tolkien and his son Christopher stripped down this particular tale to its essence, while also embedding the Chaining of Melkor within the heart of the Elves’ great odyssey to Uttermost West, strikes the mind with just how stunning The Silmarillion is as a work of art. It is eloquent and mysterious, serious and fay, beautiful and, dare I say, trippy as hell. The twists are spiritual, not textual.

That is to say, Tolkien was obviously just getting his ideas down on paper at this stage, experimenting with the depictions and machinations of the Valar and Maiar so that he could sift out the most critical and brightest elements of his mythology. So while The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr is convoluted and at times sort of silly, in my opinion it marks a critical shift to the darker and more melancholy tones of Tolkien’s vision. The magic seam is here.

I think he achieves this with one incredibly important image, an image that he will return to time and again but in different ways — a world without sunlight or moonlight. From this primordial era of the Valar to dungeons in Melkor’s fortress, from the Mines of Moria to the gathering darkness of Mordor, Tolkien is a master of light because he is willing to not only sustain darkness for chapters on end, but because he also contemplated a state of consciousness before the circadian rhythms that still dominate so much of our earthly human biology.

And so what is this one image? The dark sea — “strange was the roaring of the unlit sea in those most ancient days upon the rocky coast that bore still the scars of the tumultuous wrath of Melko.”

Wow! That’s some heady and bleak stuff. We’re talking about a vast open sea that one can hardly even see. Without a sun or moon, it lacks a horizon, so that one can imagine the sea and the sky constituting one interminable dark expanse, calling to the Elves to cross into the deep unknown. You can almost hear the waves crashing, feel the cold wind blowing, see the stars so very bright, yet far.

And yet why did the Elves decide to come to that dark shore? In this early version of the coming of the Elves to Valinor, it is as simple as Nornorë zipping three leaders of the Elves to the land of the gods, where they are then convinced to corral their tribes to make the long arduous journey west. These three Elven chieftains are Isil Inwë, Finwë Nólemë and Tinwë Lintö.

Tolkien also works in a couple striations of linguistic play here as well. We are told that these three Elves have “Noldoli” names too: Inwithiel, Golfinweg and Tinwelint respectively. The Noldoli are the people of Finwë, or Golfinweg. The Solosimpi are the people of Tinwë, or Tinwelint. And the Teleri, and the “Inwir” in particular, are the people of Inwë. For those who know their Silmarillion, some of this changes and switches fairly drastically later, either in terms of names or attributes. For example, Inwë becomes Ingwë, a slight change, but his people become the Vanyar and the name “Teleri” moves to represent Tinwë’s tribe, becoming the seafaring and sea-loving Elves.

The Teleri, who are here called the Solosimpi, become separated from each other in the great migration of the Elves to the holy lands of the Valar, across the great sea of Belegaer. For Tinwë, their chief and father of Tinúviel we are told, is lost in the wilds. It is said he lives with his spouse, Wendelin, “a sprite come long long ago from the quiet gardens of Lórien,” who is the Vala of dreams and brother of Mandos, the Vala of the dead. Tinwë Lintö is Elwë, known also later as Elu Thingol, and Wendelin is Melian the Maia, of The Silmarillion.

Again, much of this description of these tribes, their leaders, and their branching distinctions, is fairly convoluted to my mind. It could be that’s because I am also comparing this original account with the final more tidy account that Tolkien gives in The Silmarillion. It’s hard to know for sure. But after thinking about it some, my conclusion is that it was in fact tangled and messy in this first conception. Part of that is the process of creativity. It is dizzying.

However, I also believe it is because Tolkien was unsure what exactly he wanted to do with his Elves at this point. They weren’t yet his own particular vision. His Elves still had traces of “elfs,” and had a colloquial diminished quality to them. Names like “Tinwelint,” “Golfinweg,” “Inwithiel” and “Wendelin” are the hint. There are a lot of “w” name constructions here. Perhaps this is an artifact of Tolkien’s work on the “w” entries in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1920?

Perhaps Celtic mythology was high on his reading list as well — or as he would later correct others — “Welsh” mythology was, as in the stories and poems of King Arthur, Sir Gawain, and the Mabinogion. All are filled with names like Guinivere (Welsh “Gwenhwyfar”), Gawain (Welsh “Gwalchmei ap Gwyar”), Gwydion, and Manawydan. There is also Mathonwy, perhaps inspiration for Tolkien’s preoccupation with “-wë” in Finwë and Ingwë.

I think one of the breakthroughs that happened here was actually worked out through writing this chapter. Like I noted before, the final form is more concise and includes the Chaining of Melkor. But while this earliest form lacks the punch and power of his final design, Tolkien did something here that is missing in the later version, and that thing is distance, in terms of space, but also crucially in terms of time. So what we get from this version is a fuller sense of the long journey of the Elves to the home of the Valar.

While this contrasts with the speediness of Nornorë — a character I think Tolkien wisely discarded — the end result is what feels like a torturous and dangerous trek on land to a voyage at sea. Returning to the image of the “unlit sea,” personally it seems to me that Tolkien was working out two important universal phenomena — light and time. While the Valar could do all sorts of superhuman things in a primordial atmosphere and landscape, introducing organic sentient beings demands a different set of literary techniques.

For one, it seems the Elves would experience time very differently in a world without a sun or moon to mark day or night. The only temporal pulse in Eä, the World that Is — is the fluctuating silver and golden light between the Two Trees (see my entry on the Valar for a breakdown of this phenomenon). But the Trees are in Valinor and not observable by the Elves in Cuiviénen. So in a way how long the Elves’ journey took is immeasurable in some sense. Also, how Elves experienced time is a mystery too. In the earlier chapters when Eriol first meets the Elves in the city of Kortirion on Tol Eressëa, or when they tell him his mortal life is but brief in the long lives and history of the Elves, we get a little taste of this “immortal” perspective — it’s maybe a curse as much as a blessing.

So it seems to me that it is here in these “most ancient days,” that the nature of reality as it is experienced by living beings starts to truly enter the conversation in innovative and fascinating ways. One of the tricks Tolkien devises — and this may be coincidental, unconscious or conscious, or all at once — is that Tolkien ties the coming of the Elves both to geologic and astral time. Geologic in the sense that they awaken next to a lake that no one really can place on a map — something Tolkien smartly leans into in The Silmarillion, when he tells us that the lake is gone, lost to changes in the landscape. Astral in the sense that the very first description of the Elves is as “folk who gaze in wonder at the stars.”

Which brings us back to time versus light, and Tolkien’s unique linguistic aesthetic versus the names in Welsh legends that he admired. He had to find his own way, and he did it by tapping into the senses. As we’ve discussed before, his origin myth — his Genesis — starts with the metaphor of music. And as his Book of Lost Tales progresses, he brings in darkness and light, and starlight, and like waves roaring on a rocky coast, the great fate of the Elves rolls over the land. In the long lapping waves of his own life, we know quite clearly that this process also yielded a more original and more delightful aesthetic sensibility — this is still subjective, but for me his names bested any Welsh-isms and stand apart. I’m not going to go deep into the aesthetic power of Tolkien’s invented languages here. A good place to dive into that topic is my entry on his names. But I will say here that some of his better names at this foundational stage are his simplest ones.

Which brings us to Ulmo and Falman-Ossë, and Uin and Uinen. These four names to me are pure Tolkien. Ulmo is an iteration on the fairly common Elmo, but a sly brilliant appropriation, the shift from “E” to “U” in the first letter a masterstroke. It also has the benefit of alluding to St. Elmo’s fire: the atmospheric phenomenon brought on by electrical charges from shifting weather — including as harbingers of lightning strikes — has long been revered by sailors. But “Ulmo” has a deeper tone, conjuring “underwater” and “ultimate.” And Falman-Ossë takes an already strong construction in “Ossë” — perhaps a sonic play on “O’sea” — and adds “Falman,” which Tolkien adapts from the root “fala” for “Falathrim” and “Falmari” — meaning “coast people” and “wave-folk” respectively.

Uin does not survive into The Silmarillion, but is remarkable because he is a whale — there is no other whale in Tolkien’s mythology that comes to mind. Perhaps we will meet more whales in THOME, but here we are told that Uin is the “mightiest and most ancient of the whales,” whom Ulmo summons to help drag the Elves on an island across the sea to Valinor. Uinen, the wife of Ossë is not given a big role in this major event but in later legend we learn that she cared for all sea creatures and alone could help calm the wraths and rages of Ossë and his sea storms. Here she mostly just aids Ossë in a tug-of-war with Ulmo and Uin, helping tie the isle down to the sea-bottom with “giant ropes of leather-weeds.”

The tempestuousness of the sea is a critical aspect of the crossing of the Elves to Valinor. Falman-Ossë does not want the Elves to leave Middle-earth and hole up in the land of the gods. He wants them to stay in the wilds — and along the many great coasts of the Great Lands. But he also simply wants to spite Ulmo for using his island to carry the Elves without asking. There’s a lot of clashing here and the back and forth between Ulmo and Ossë feels at times forced and overly convenient, as if Tolkien was drumming up conflict to give this chapter excitement and some plot propulsion. It’s an ordeal to get to Valinor.

Ever a master of description — “world-building” that is — we can tell here that Tolkien was building up fantastical sediments and contours and motivations that could fit with his bigger philosophical ambitions as they evolved into ever grander gestures and feats of the imagination — laying the groundwork for all that would follow in the years ahead, from The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings and finally The Silmarillion. We’ve discussed the dimension of time quite a bit, but as we consider how different dimensions and senses can work together I think now it is important we return to the motif of light and darkness.

Rhythm is critical in any narrative that ties its themes and imagery to light and darkness, not just time, especially when we’re talking about a time before there was a sun. In many different parts of The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr, the image of darkness is repeated: “Shadowy Seas,” “unlit sea,” “Shadow Folk” and “deepest shades,” “floated darkly,” “dark waters” and “darkling glade.” More than any of the previous chapters, Tolkien is driving home the idea that much of this old world has no light or radiance like the sun or the moon, except for the Two Trees in Valinor, a spiritual light that echoes back to the music of Creation.

By doing this, Tolkien was playing with both the sensual and the spiritual, as well as the primal. When it comes to light and darkness, there is perhaps few things as powerful in the biology and psychology of humanity. Of course water is another elemental fact of life, its liquid undulations reflecting the waveforms of energy that spread throughout the universe, both oceanic, cosmic and temporal. With water, Tolkien ties them all together — time, light, music — on a dark sea.

And it is the play of light on the waves that Tolkien excels at, as he picks up his pace and dexterity the further we read into The Coming of the Elves and the Making of Kôr. I won’t got into all of the imagery here, but it is in Ossë’s moodiness that it seems Tolkien delighted here. His motivations feel false and petty, but his pain and his alienation do not. One sweet passage describes how Ossë’s love for the Solosimpi beckons him close to their abodes along the shores and caves of Tol Eressëa, Eldamar, its coasts, and the opening to Valinor in the Bay of Faëry.

“Indeed war had been but held off by the Gods, who desired peace,” writes Tolkien, touched himself by war. “Therefore does Ossë sometimes ride the foams out into the bay of Arvalin and gaze upon the glory on the hills, and he longs for the light and happiness upon the plain, but most for the song of birds and the swift movement of their wings into the clear air, grown weary of his silver and dark fish silent and strange amid the deep waters.”

Now we’re getting closer to what Tolkien’s Elves mean to Ossë through the love and anger of Ossë and his battles with Ulmo over their migration from Middle-earth to the landlocked homes of Valmar. He wants his “children” to be nearer. He wants their company among the waves.

But tn The Silmarillion, this convolution and strife has a wholly different reason for its drives. What we are told is that Ossë is not fearful or resentful of his lord, Ulmo, but that Melkor for a time corrupted and confused him, and that it was Uinen and Aulë who persuaded him to return to Ulmo.

Christopher Tolkien makes a point of this in the chapter’s endnotes. As he emphasizes, in The Silmarillion, it is Ulmo who counsels against the Eldar migrating to Valinor and Ossë is simply helping him delay their crossing.

In the same rich vein, when Oromë first finds the Eldar in Cuiviénen, he learns that they are also filled with some fear. For a “dark Rider” it was rumored would come among them and hunt them, or was it perhaps that Melkor had propagated lies among the Eldar that a Great Rider would prey on them, so to turn them away from Oromë when he found them? Tolkien offers both as possible.

This is a subtle but incredibly important shift in the mythology. As I pointed out in our previous entry on THOME, the convolution of evil in The Chaining of Melko rings false, because in the later evolution of Melkor into Morgoth, Tolkien moved from a Classical conception of evil to one that incorporates a deep moral view of the universe, similar to the hybridization of Christianity with Platonic thought achieved by the Roman philosopher, Boethius.

This begins to give Tolkien’s Elves more purpose, and his imagery of shadow and light more poetic meaning. While there are only traces here, they are still striking when they flash in the darkness.

“Twice now had that isle of their dwelling caught the gleam of the glorious Trees of Valinor” — the holy trees: silver Silpion and golden Laurelin. And that once twilit isle becomes Tol Eressëa, carried back and forth, ferrying the Elves to Valinor, until it settles just off the coast, the brilliant light of the Two Trees beaming through a seam in the mountains of Valinor.

Earlier in the chapter, it is worth rereading to better understand that in the darkness of the world, one without sun or moon, it is this spiritual organic radiance that beckons the Elves “home” to the unknown.

When Isil Inwë, Tinwë Lintö and Finwë Nólemë first come as ambassadors to Valinor, Manwë, the leader of the Valar, asks them how they came into being, how they found the world, and what desire has entered their hearts? For Manwë also knows they are Consciousness itself, emerged from a deeper ocean of space and time, interlinked with him and all that is, and here he is asking a reflection to reflect on what lies beyond and before it awoke.

But Nólemë answering said: “Lo! Most mighty one, whence indeed come we! For meseems I awoke but now from a sleep eternally profound, whence vast dreams already are forgotten.” And Tinwë said thereto that his heart told him that he was new-come from illimitable regions, yet he might not recollect by what dark and strange paths he had been brought; and last spake Inwë, who had been gazing upon Laurelin while the others spake, and he said: “Knowing neither whence I came nor by what ways nor yet whither I go, the world that we are in is but one great wonderment to me, and methinks I love it wholly, yet it fills me altogether with a desire for light.”

Who is “me” who seems and thinks? It is we. And we dream and we love, and yes, we certainly need and desire light, even when the darkness is not evil, even when the sea is shadowy, even when we can’t perceive what lies beyond that invisible horizon, whether it be the edge of the world, the door to death, or the distant twinkle of the stars. Cast out or invited in, land or sea, it is still the music in everything, the play of light and shadow, that dazzles “me”. Just ask Ossë…

“Far behind lay Tol Eressëa in silence and its woods and shores were still, for nearly all that host of sea-birds had flown after the Eldar and wailed now about the shores of Eldamar,” Tolkien writes. But “Ossë dwelt in despondency and his silver halls in Valmar abode long empty, for he came no nearer to them for a great while than the shadow’s edge, whither came the wailing of his sea-birds far away.”

*Melkor is the chief villain and approximates Satan in Tolkien’s works.

**The Valar are the gods of Tolkien’s mythology. The Eldar are the Elves.

***The Children of Ilúvatar are higher order sentient beings created by the God of Tolkien’s mythology, who is named Ilúvatar. They include Elves and Humans, and by extension or adoption, Hobbits, Dwarves and Ents. Valmar is the name of the main city in the land of the gods, Valinor.

Our History of Middle Earth Journal Index - The Book of Lost Tales, Part One:

The Cottage of Lost Play / Opening the Heart of Modern Myth

The Music of the Ainur / Tolkien’s Creation and the Creator

The Coming of the Valar / The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder, Part One

The Building of Valinor / The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder, Part Two

The Chaining of Melko / Who the Hell is Tinfang Warble?

The Chaining of Melko / The Convolution of Evil in Middle-earth

The Coming of the Elves / Tolkien’s Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems

The Making of Kôr / Tolkien’s Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems, Part Two