The Convolution of Evil in Middle-Earth

How 'The Chaining of Melko' changed the course of Tolkien's mythology

“Yet nothing do you know of the coming of the Elves, of the fates wherein they move, nor their nature and the place that Ilúvatar has given to them. Little do you reck of that great splendour of their home in Eldamar upon the hill of Kôr, nor all the sorrow of our parting. What know you of our travail down all the dark ways of the world, and the anguish we have known because of Melko…”

Verily, is this not J.R.R. Tolkien himself telling us, not just the elf host Vairë telling Eriol the mariner in Eldamar, of the great sorrows and anguish that he, Tolkien, suffered? And did he not create his Valar, and his Elves, and their strange beautiful languages and names, to bear witness, to hear him, and to commune in that sorrow? And is not here, in his creation of Melko, Melkor, Morgoth, that he contemplated the nature of evil, and the source and sorcery of all torment?

These are the questions that come to me as I read the fourth chapter of The Book of Lost Tales: Part One, of the monumental History of Middle-Earth (THOME). These are no small things, though they started as small murmurings. In some ways, some of Tolkien’s earliest imaginings were twee and quaint — just think on his Tinfang Warble, or the name he gives one of his Elven tale-tellers, Littleheart — while still many of his inventions were mind-boggling in scale from the very beginning.

It is this aching expansiveness — the desire for Faërie, Fantasy and Escape — that both dazzled generations enchanted by Tolkien’s spells and inspired hatred by so many literati, who feared the ancient frontier, beyond the mystical walls he tore down. So that The Chaining of Melko is rich with consequence, as it contains the first true convolutions of Tolkien’s moral physics, where we can detect him “working out” great questions about the human condition, and the evils of treachery and betrayal.

This fourth chapter starts off harmlessly enough. The narrative itself lacks the full power Tolkien would later achieve with its last form in The Silmarillion. Still, it is important here to contrast two helices that the chapter relates. On the one hand is Eriol, the human mariner enchanted with the songs and tales of the elves. Eriol wants to drink the magical elixir limpë. He is told by one of his elven hosts that limpë can heal the longing that Tinfang’s music stirs. So Eriol goes to the elf queen, Meril-i-Turinqui.

In a sense then, this is about seeking abatement from the profound longing that divine music puts in our hearts — that deep chord of time that stretches inside us the knowledge of a greater universe within the confines of a mortal body. “And a marvel of wizardry liveth in that fluting,” Eriol says of Tinfang’s music — here, Tolkien, as we know from his later essays and writing, is giving us an inchoate articulation of his theory that Faërie represents an ancient, almost biological yearning for home, i.e. heaven, enlightenment, our deepest truth, “God.”

“Now, however, for such is the eeriness of that sprite, you will ever love the evenings of summer and the nights of stars, and their magic will cause your heart to ache unquenchably,” Vairë tells Eriol. For such is the “cost” of enchantment, of living life in the light of the divine — a mirror, one might say, and mythic counter to the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.**

And yet, Eldamar is not Eden. Limpë is not the blood of Christ. And Eriol is not an apostle of Jesus. Still, these echoes and harmonies are there, I believe, whether by intention or unconscious, however deeply hidden. For Tolkien’s Catholic vision is genius for exactly that reason. That these deeply engrained Western, and in many ways Eastern, and global mythic codes, are both there and not there — invisible and perceivable, Seen and yes, Unseen. Here is the power of Tolkien’s mystical game already in the make.

On the other hand, is the story queen Meril-i-Turinqui tells Eriol about “Melko’s Chains,” which holds in its words, penned from Tolkien’s hand sometime during or after 1917 in his first years recovering from his service on the Western Front in World War I, a great struggle that would shape his views about technology and the power of lies in moving peoples against each other.

We’re no longer in the cosmic or more theistic moral register of the first three chapters of THOME. Here, with the treachery and evil of Melko growing before them, we get a moral conundrum that the Valar must acknowledge and unwind. And where this leads is to subterfuge and ultimately the binding of another god’s hands and feet — the abrogation of Melkor’s freedom.

Why must they chain him? Well, it’s fairly simple. Melkor — Tolkien’s chief divine villain and Lucifer-type — has been defiling and ruining everything he can, and then corrupting nature, breeding monsters and fell creatures. He’s hiding out in his underground fortress in the far cold north, called Utumna (“Utumno” in The Silmarillion). So after realizing that Arda — the Elvish name for the world — is going to hell, literally, they decide to march forth to bring old “Melko” to heel.

But the poisoning of the earth starts off behind the back of Manwë, Lord of Arda, and his divine brethren. For Melkor had caused pain before when he undermined the Lamps of the Valar, after which they decided to settle and fortify Valinor. Unfortunately, as they regrouped, Melkor continued his treachery, slowly but surely undoing the beauty of their labors back in Middle-earth.

“Then things began to grow there,” Meril-i-Turinqui tells Eriol, “Fungus and strange growths heaved in damp places and lichens and mosses crept stealthily across the rocks and ate their faces, and they crumbled and made dust, and the creeping plants died in the dust…” So the queen recounts to us in her voice, but like Rúmil, also in Tolkien’s voice — that the music of Melkor deranged and destroyed much of the mortal world in the Valar’s absence.

It takes the goddess Yavanna — Tolkien’s earth diety — to first notice the Great Enemy’s deception. At first, the Valar, now at peace in their new home of Valinor with their peoples, are slow to react. It takes Yavanna’s tears and pleading, and the anger of like-minded Valar like Tulkas, Oromë and Aulë to rally the other Valar to action. Manwë, who is characteristically reluctant to go to war or resort to violence, proceeds carefully as the gods start to complain and rally against Melkor’s violations.

It is then that Manwë holds a council and the Valar develop a “plan of wisdom.” Does this sound familiar to anyone, for here to a degree however slight is Tolkien’s template for the Council of Elrond and the slow deliberate action of the good against the evil in The Lord of the Rings.

The morally wise, in other words, are not rash or overly quick to action, in Tolkien’s conception. That is why Tulkas, while stout of heart and quick to laughter and joy, even in the face of great evils, is not considered among the wisest of the Valar, even if he sees through Melkor’s treachery more than the others and is quickest to defend what is good and right. Hence, the music and patterns of the universe have a higher and deeper order that the greater gods Manwë, Varda and Ulmo consider more carefully than the others in the pantheon.

It is the synthesis of these competing tensions, under pressure by Melkor’s great evil, that the Valar decide to make a chain made of many metals enchanted by the smith-god Aulë, which is called Angaino (later “Angainor” in The Silmarillion). It is made of a compound of metals called tilkal (sharing some of the same alphabetic formula as Tulkas). What is important about Angaino is that it is unbreakable. It has manacles and fetters that will bind Melkor’s hands and feet.

How then to get Angaino clasped on Melkor? The chain is incredibly heavy. Even Tulkas, the strongest of the Valar, can barely carry it, we are told. Also, Manwë is hesitant to hurt or imprison any fellow god. His reluctance to judge and to punish is classic Tolkien, based in Christian humility and compassion for wrongdoers. So while little of his mythology is recognizable as Catholic, based for the most part in more universal moral physics, the consciences of many of his most important characters more clearly share that heritage. Manwë is a clear example.

Just as Melkor is Tolkien’s exemplar of malice, he paints his diabolical god not so much through descriptions of his person, but more through his lair. For this liar is twisted and twisting in every sense of the word, wrenching rock and mountain, grinding ice, breeding foul beasts in pits and caverns, constantly scheming to deform, deceive and destroy everything that he cannot command as his own:

“There sat Melko in his chair, and that chamber was lit with flaming braziers and full of evil magic, and strange shapes moved with feverish movement in and out, but snakes of great size curled and uncurled without rest about the pillars that upheld that lofty roof. Then said Manwë: ‘Behold, we have come and salute you here in your own halls; come now and be in Valinor.’”

Here lies a key inflection in the history of Tolkien’s legendarium, when he explored the sometimes blurry and grey lines between the true and the false, between persuasion and manipulation. Like undercover cops, the Valar go into Melkor’s hall under the pretense that they are asking for his forgiveness, playing to his need for validation, assuring his ego, and inviting him to Valinor to take a place of pride, thus setting a trap for the Master of Lies.

Christopher Tolkien, who edited and contextualizes THOME, points out that this cunning form of stratagem by the Valar is not repeated in the final version of this story, Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor, in The Silmarillion. This is telling, because it seems Tolkien pulled back from this more convoluted tale of mastery. “In its rich narrative detail, as in its ‘primitive’ air, the tale told by Meril-i-Turinqui of the capture of Melko bears little relation to the later narrative,” writes Christopher, “while the tone of the encounter at Utumna, and the treacherous shifts of the Valar to ensnare him, is foreign to it likewise.”

It is in fact Aulë, the same Vala who forged the adamantine chain Angaino who also devises the ruse that lures Melko into the Valar’s grasp. It is here, I believe, in some fashion, exists the later vestige of the idea that Aulë shared a sort of kinship with Melko and Sauron, a creativity and ingenuity that could dazzle but also trap the ego in a kind of pride of creation, that can only ever be an echo of the One, Eru, Ilúvatar — God. The symbol of the chain is therefore an apt one, for it represents control and restraint as much as bondage and entanglement.

“To this Manwë assented, saying that all their force might scarce dig Melko from his stronghold, whereas that deceit must be very cunningly woven that would ensnare the master of guile. ‘Only by his pride is Melko assailable,’ quoth Manwë, ‘or by struggle as would rend the earth and bring evil upon us all…’”

And so, rather than risk greater violence and ruin, Manwë opts for the stealthy trick, one that Melko bites like a fish to worms on a hook. In some ways, this casts Melko as slightly pitiful, not unlike, it seems to me, Gollum, when he is tricked by Frodo into the clutches of Faramir’s Rangers of Ithilien by the Forbidden Pool. It is not to say that Tolkien in either case is arguing that hiding one’s intent is never warranted. In the case of Gollum, Frodo is trying to save Gollum’s life. Nevertheless, it is a decision that Gollum never truly forgives.

The end does not justify the means, is a moral law that Tolkien takes very seriously in his stories, and it is through this sometimes grey standard of human behavior, that he sheds great light onto our conscience. That is why, when reading about the subterfuge of the Valar in order to snare Melkor, it somehow rings slightly false, for Tolkien had not yet perfected the twists and turns in his mythological morality chain.

At this stage, the gods are in many ways rendered too human, too wrapped up in the needs of mortal physics. They come across like the Greek gods as rendered by Homer and Aeschylus (both big influences on Tolkien), characters that seem to fuss and ache with some of the same emotions, often petty emotions, that mark humanity with so much tragedy.

I think it is to Tolkien’s credit that he later pulled back from this level of anthropomorphism and dramatization in The Silmarillion. Instead, his gods are deeper reflections of our organic being and our material world — achieving a more remote and deeply aesthetic spiritualism.

But what does that mean? Well, I think we can think about this in a couple different ways. For one, Tolkien wrote The Chaining of Melko when he was around 25 years old, having survived orphandom after the death of both of his parents. He knew tragedy. He knew all too well the “sorrow” and the “anguish” of loss. And yet, here, writing about such eternal questions as the origin of evil, perhaps overconfidently, he infused that darkness in the being of Melkor.

In 1916, he would fight for his life in the Battle of the Somme, losing two of his best friends to war and witnessing what he clearly believed was hell on earth — tanks, artillery blasts, machine guns and mustard gas. It turned out, he did not yet know the full measure of sorrow and anguish the world contains. It is poignant, as one reads these early, philosophical musings by Tolkien, to know that he had only recently gained the knowledge, painfully, that would make his later treatments on the nature of evil and deception so tragic and intuitive.

Here, it seems to me, he is still very early in developing his voice and wisdom on the dynamics of loss and evil, and the experiential nature of the universe, and exploring the contradictions in the concept of the “great chain of being.”

Meril-i-Turinqui, who Eriol “mariner of many seas” meets in Kôr in Eldamar where the tower Kortirion stands tall, precursor to Tirion on the hill of Túna in The Silmarillion, where the hero Eärendil will come to plead the Valar to help save the world from Melkor’s torments eons after the chaining of that Lord of the Dark, and yet eons before Eriol’s encounter with Vairë and the Elves, refuses to give him limpë — for that draught of magic, she tells him, would only fill his human heart with greater longing still: “O Eriol, think not to escape unquenchable longing with a draught of limpë — for only wouldst thou thus exchange desires…”

Let us not forget that it is Melkor who is filled with the greatest desire, the desire to master the world and to shape it even greater than the light to his shadow, the Creator, the first thought, the first power. For it is desire itself — even the desire for Faërie, for Fantasy, for Escape — that entraps us. The more we want, the ever more we want to step outside our fates, to shape our own destinies. That is, as Tolkien so skillfully dramatized and mythologized, the gift of mortality and attraction of immortality constrict in often cruel ways.***

The chain Angaino in itself is a kind of mental prison. When Tulkas leaps through the air after Melko demands Manwë to kneel before him, even after Manwë offers him entrance to Valinor without penalty, both helices connect. The Giver of Freedom, as Melkor would call himself, is punched in the mouth; our fates interlocked, even the gods cannot unravel the chains of the universe.

So the trap has sprung. The convolution of evil is turned another knot, and then another, and more, escalating until Melkor is fooled and brought low. Chained, he is then taken to the halls of Mandos, where he languishes for many ages, a time of great peace and quiet. But we know this will not last. We know that they’ve only brought the devil into their home and the heart of their holy land.

“Yet did they purpose,” writes Tolkien, “if naught else availed, to overcome him by force or guile, and set him in a bondage from which there should be no escape.” And so Tolkien would turn his own bondage into an awakening, not just for himself, but an escape for the world.

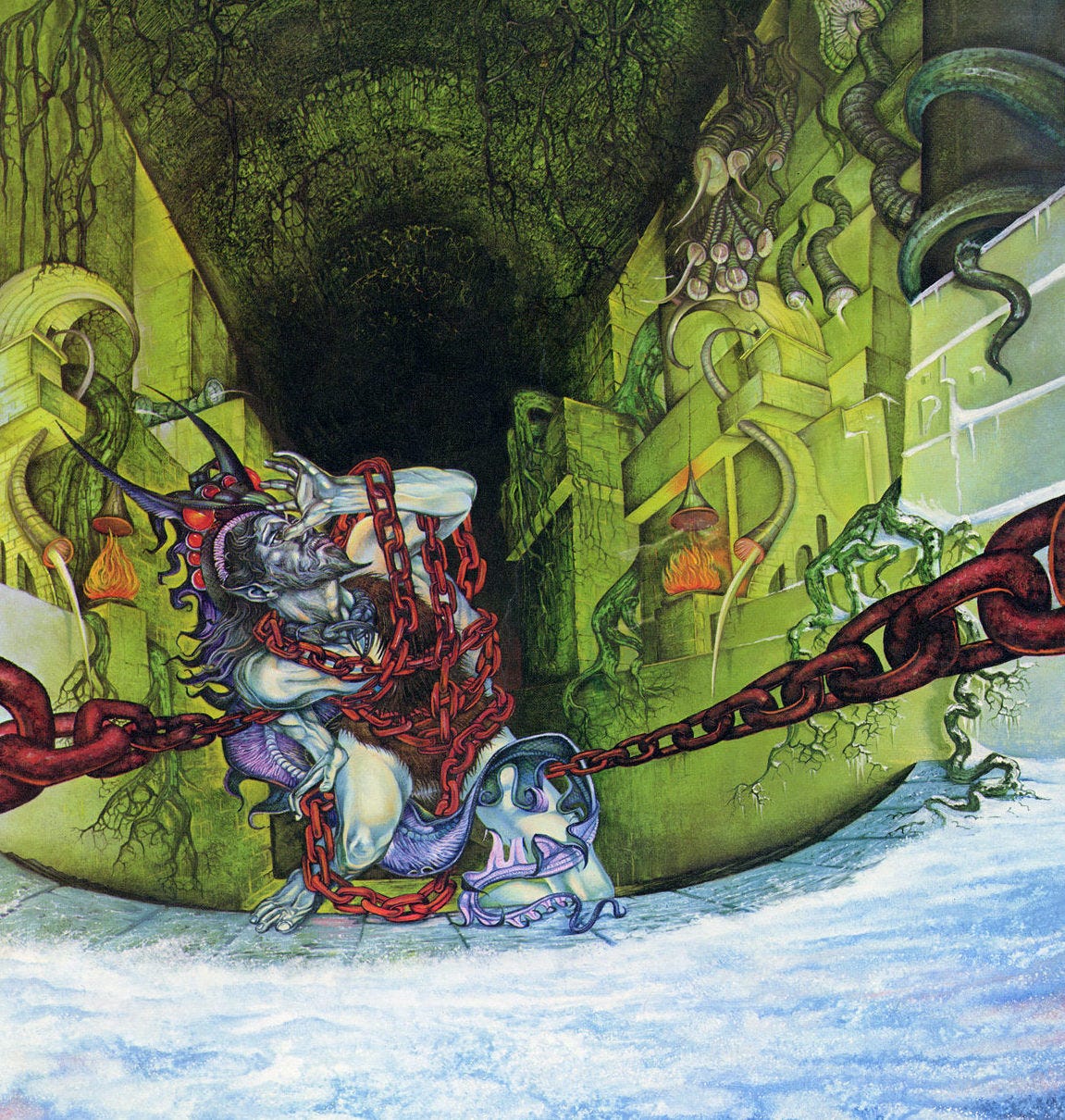

*The remarkable oil painting Tulkas chains Melkor is by the up-and-coming Tolkien artist Jay Johnstone, whose recent printing of Tolkienography, a collection of some of his works, is a revelation. Inspired by romanesque Renaissance art, his rendering of the great Tulkas is the first and only yet made or known.

**Here I am referencing Genesis from the Bible, and the foundational Western myth about the origin of sin, temptation and shame. It is quite obvious, but the serpent (a motif that shows up in Tolkien’s Chaining of Melko) is not unlike the twists and turns of moral ambiguity, which comes to us in the form of lies and deceit from Satan in the Bible, and has its counteraction in Tolkien’s myth as a strong iron chain. Also not to be overlooked, is Yggdrasil, the Norse mythological Tree of Knowledge, which also influenced Tolkien, in terms of the intricate paths and competing centers of fate and action.

***Another important image I’m detecting in Tolkien’s chain (Angaino) is not just the laws of fate — and hence the vicissitudes of good and evil — but that of the snake or serpent. While we’re alluding to the serpent in Genesis, there is also Jörgmungandr, the World Serpent of Norse mythology, which also finds wily expression in Tolkien’s later conception of the One Ring.

Our History of Middle Earth Journal Index - The Book of Lost Tales, Part One:

The Cottage of Lost Play / Opening the Heart of Modern Myth

The Music of the Ainur / Tolkien’s Creation and the Creator

The Coming of the Valar / The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder, Part One

The Building of Valinor / The Valar, Gods of Wisdom and Wonder, Part Two

The Chaining of Melko / Who the Hell is Tinfang Warble?

The Chaining of Melko / The Convolution of Evil in Middle-Earth

The Coming of the Elves / Tolkien’s Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems, Part One

The Making of Kôr / Tolkien’s Elves: Dark Seas, Bright Gems, Part Two